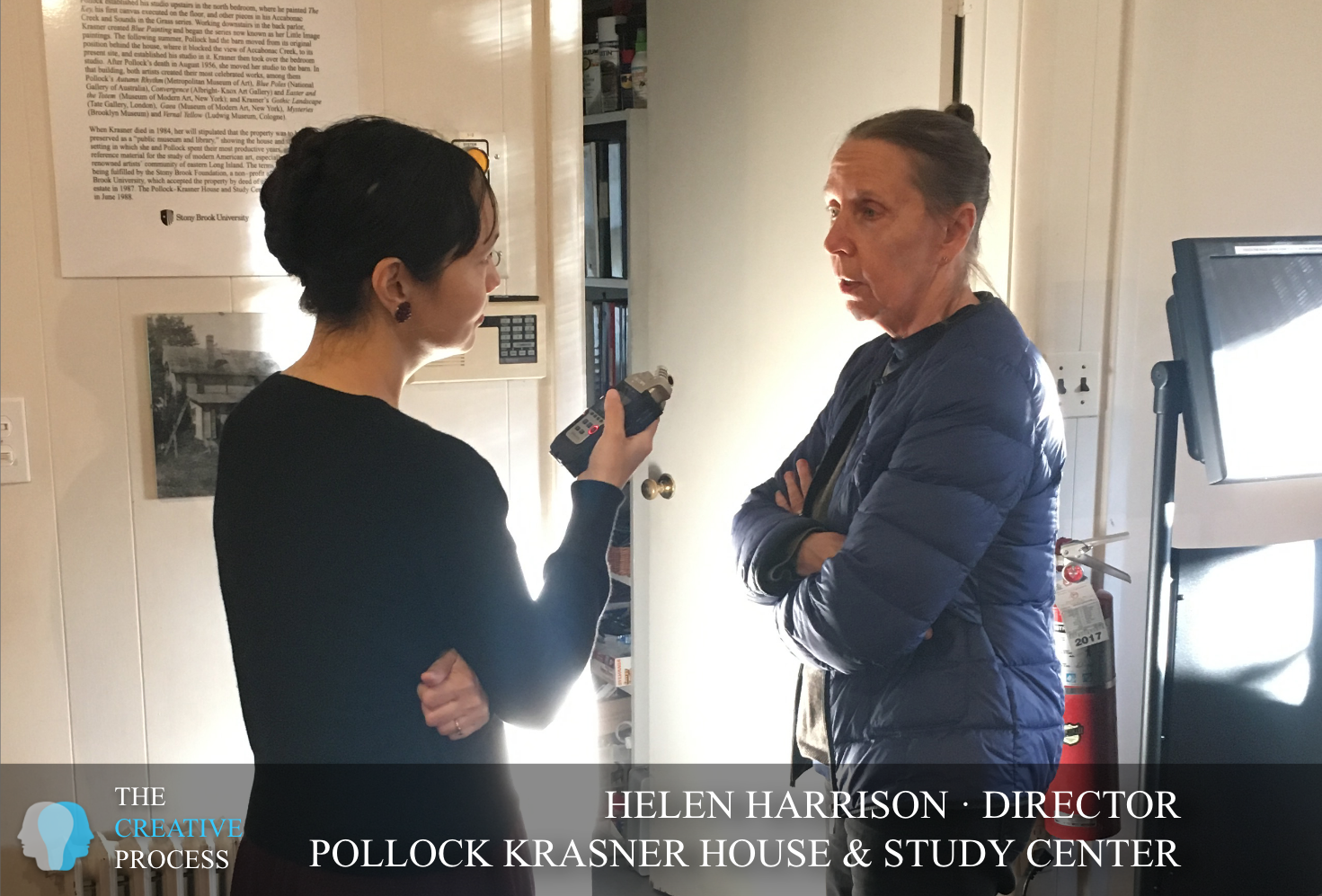

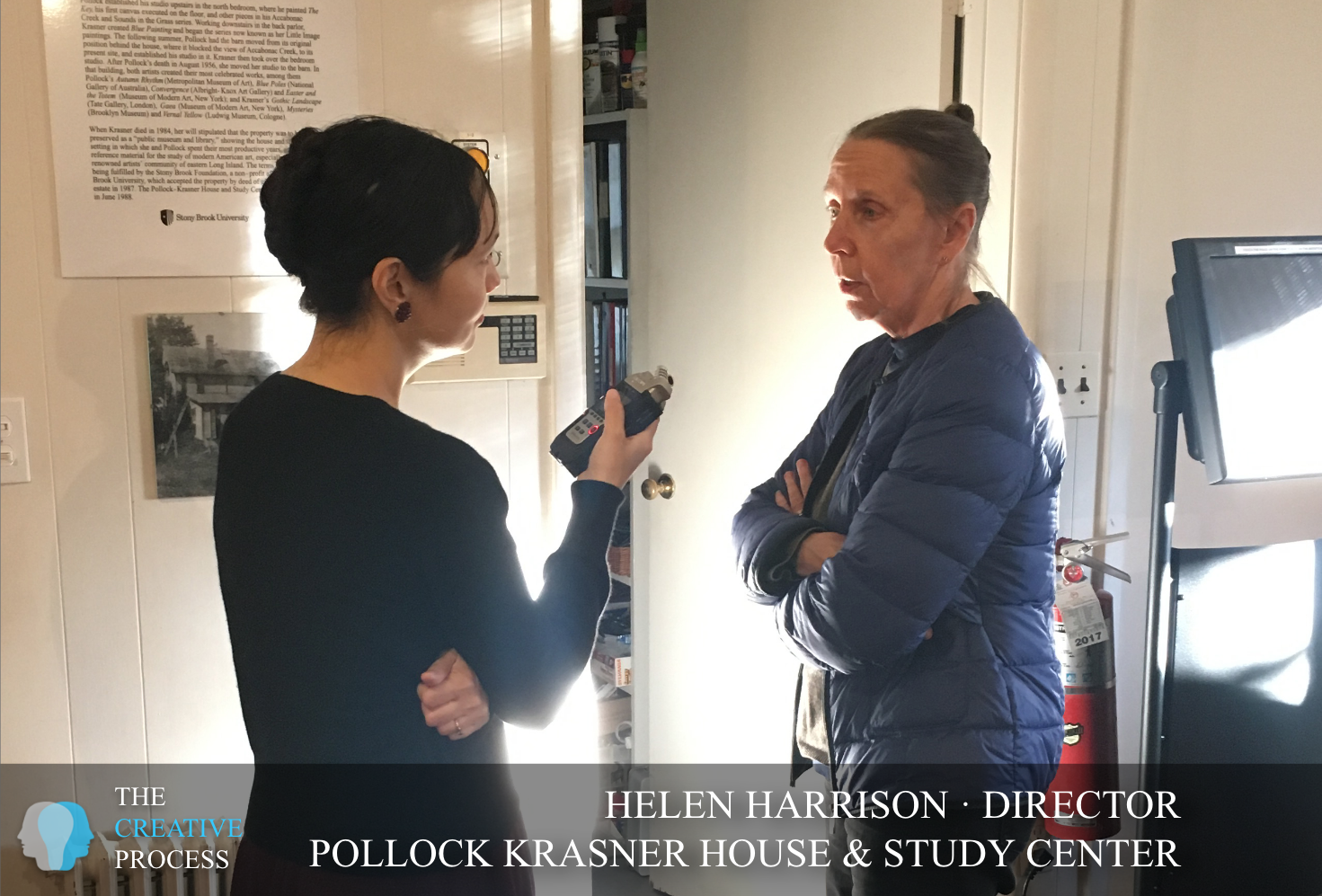

Helen A. Harrison is the director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center and an authority on 20th century American art. She is the author of Hamptons Bohemia and Such Desperate Joy: Imagining Jackson Pollack. In 1990, after serving as curator of the Parrish Art Museum, director of the Public Art Preservation Committee in Manhattan, and curator of Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, she became the director of the Pollock-Krasner House, a National Historic Landmark museum and research collection in East Hampton. She has lectured widely at Stony Brook University, the School of Visual Arts, and other universities. For five years her visual art commentaries, “Art Waves,” were heard on NPR affiliate WLIU 88.3 FM.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So we're standing in the Pollock Krasner House & Study Center. Could you just tell me how long you've been associated and how you came to be director?

HELEN HARRISON

Well, I've been here since 1990. I am not the founding director. The museum opened in 1988. There was someone here before me, who actually started it and set it up, but she was part-time. And, as far as I'm concerned, she did an excellent job, but she didn't want to take it as a full-time job. So, I was the curator of the local museum, Guild Hall, at the time, and I knew Meg Perlman, who was my predecessor and who was really responsible for getting the place up and running. And then, when she decided to leave, I applied for the job.

* * *

...They both came up during the 1930s. He went to The Art Students League and studied with Thomas Hart Benton, and then he went to a couple of the settlement house free classes, and he apprenticed for a while with a stone carver, but he finished art school at the depths of the Great Depression, as did Lee. She went to The Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design and, fortunately for them, the WPA [Works Progress Administration] came along. The Federal Art Project.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

That was so important to many artists in that period.

HARRISON

Oh, my gosh. The whole generation was saved from starvation, practically. But the great thing about it, in addition to them being able to earn a living wage, they were free from commercial pressure. So they were able to develop artistically without having to worry about marketing their work. So they didn't need dealers. They didn't need collectors. They didn't need critics. They had Uncle Sam!

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Oh, it's great. It puts you in touch with, you know, I think that it's a distraction for many, a necessity, but distraction of thinking about the commercial. Who's going to buy this?

HARRISON

Yes!

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And so much about being an artist is just being able to work on a daily basis. It's like a repertory, and you have your community and that is so nourishing and so to have that free from worry is so important to an artist's development.

HARRISON

In her will, Lee made provision to set up a foundation to give grants to artists.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's very generous. It's still going...how many years?

HARRISON

Yes. Over 35 years. And, well we call it Lee's private WPA, because that's exactly what it's intended to do, is to give artists time to do their work without worrying about the money.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Are they connected to the House or you?

HARRISON

We're separate. We belong to Stony Brook University, which was done deliberately in her will. She wanted to separate the two functions, but they have been very generous to us. We're joined at the hip, shall we say, but they do have a primary function of their philanthropy is helping individual artists.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's so lovely when artists do that.

HARRISON

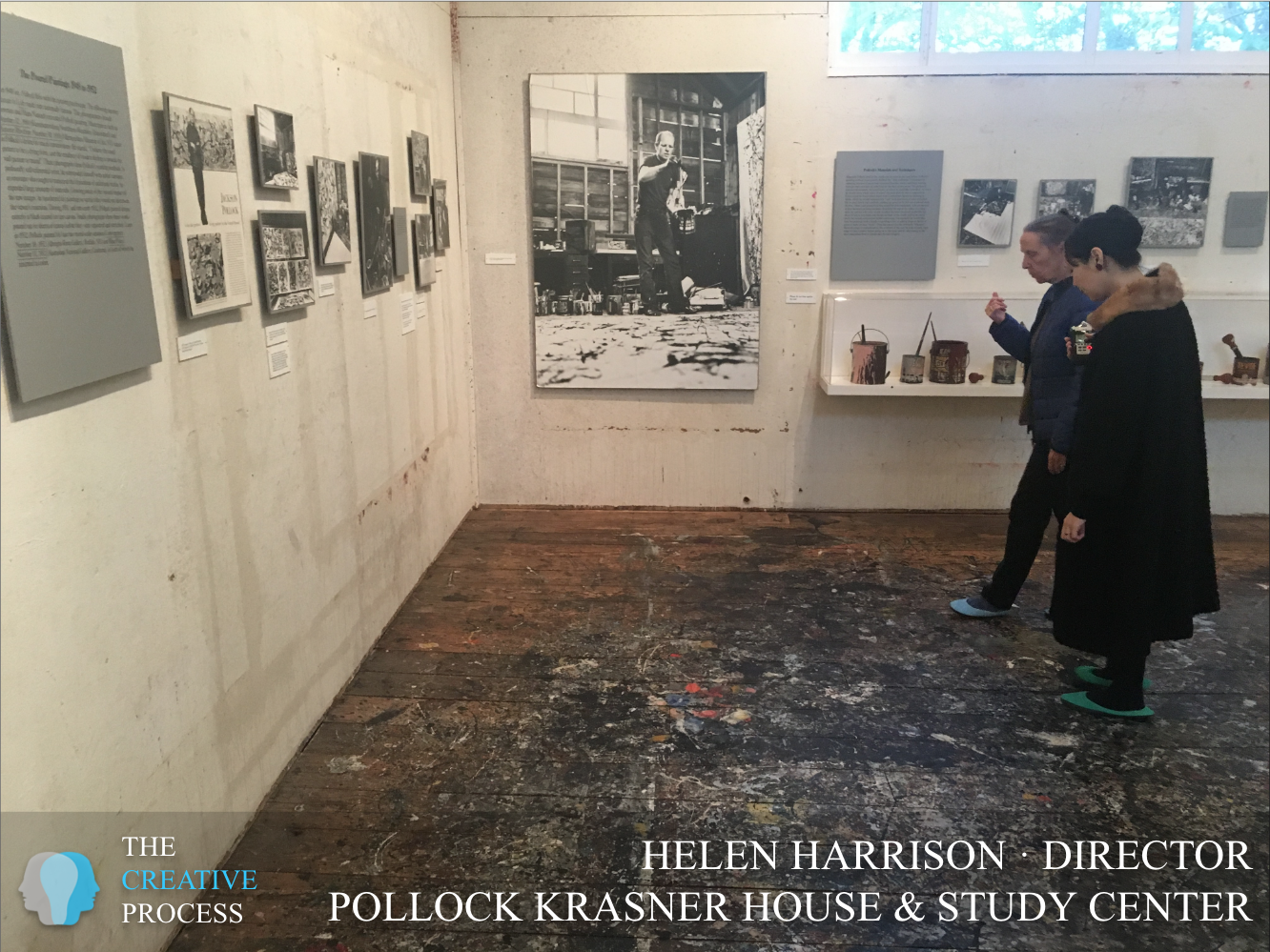

Well, the whole thing about the creative process is that it takes time. It's not, people think of Pollock as someone who just blurted out these drippy images and then went on and blurted out another one. It's not like that at all. It's very time consuming because there's a great deal of concentration involved and then contemplation. So after the first campaign is completed, you have to step back. You have to maybe hang up on the wall, maybe put it down on the floor. Leave it there, and think about it and decide what you're going to do next. Then if it doesn't work, you've got to make it work.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's not just what you see. It's all the decisions.

HARRISON

The decisions that are in–and now in Pollock and Krasner's case, it may be a very spontaneous process. Very intuitive, but it's still very time-consuming.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And energy, you can see the energy in the canvases.

HARRISON

Well, that's it. He said it himself. “It's energy and motion made visible.” So these are things that come spontaneously from his own feelings, but they're based on, first of all, observation, the natural world around him, all the forces of nature that were so influential. And then, processing that and figuring out how to create a visual language that expresses those feelings. And some of those feelings can be very complicated.

The technique, the means of expression is dictated by what those feelings are. It's not the other way around. People think – Oh, he used the liquid material and then he sort of danced around and that kind of gave him ideas. – No.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And that's the thing that's interesting is he did get into the paintings, and I think that that's how we can get into them. We enter them. He approaches it from every angle. Yeah, it's so involving. It almost surrounds you...

HARRISON

Yeah, even the smaller ones when you get up close to them. All of them have kind of an ideal viewing distance. Some of them you really want to step back from them and contemplate them and then others really draw you in. Even ones that are only medium-sized to sort of borderline.

Well, for example, there's one that's just been conserved at L.A. MOCA. It's this one. Number 1, 1949. It's not huge, but it's just for me the right size because it's not overwhelming. But it's big enough that as you get close to it, it begins to expand out in your line of vision and it's just got a lot going on in it too. It's very colorful.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

We didn't really speak about, I'm thinking of the women. Women are important in his life.

HARRISON

Very much so.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

His mother. If we could talk about the positive and maybe even the women who brought out some destructive elements, as you think towards the end.

HARRISON

Towards the end, yes. But his mother was very supportive. Surprisingly so for a farm wife, and the family, they were never destitute, but they certainly struggled. They were very working class. But his mother encouraged all the boys to be creative. Five boys!

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Charles, as well.

HARRISON

Charles was the eldest, and he's the first one who came to New York to study with Benton. But then Sandy came, Jay came, Jackson came, and Frank stayed in California. He married into a rose growing family, but the other four boys all came east. It was very unusual, when you think about it. If you would imagine the stereotypical farm wife, she would want the boys all to be doing farm work, but she encouraged them to be creative. And then, of course, he had a couple of female psychiatrists who helped him very much. Lee, of course, Peggy Guggenheim, Betty Parsons, they believed in him and they took a chance on him.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What have you learned about creativity, about artists? What drew you to art?

HARRISON

Well, I started as an artist.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes.

HARRISON

I went to art school. I studied art in college. I had studio art. I specialized in sculpture, but I also did painting, printmaking, ceramics, and all the other things you do as an undergraduate. Then I went on, for graduate work, in sculpture at The Brooklyn Museum Art School and at Hornsey College of Art in London.

I met my husband at The Brooklyn Museum, and we married in '67, and then I went to live in England for a while and practiced as a sculptor. So, I did have a background of my own creative expression. And when I started studying the WPA, which was my scholarly specialty, I went back to graduate school to do that, some of my teachers had been on it and told me about it. So I related to them on a personal level and a professional level. The artists here, we're talking 40 years ago, they were still alive. So you could call them up or go visit them and talk to them about it. I was very comfortable with artists because I was one.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Right. That is so important.

HARRISON

Well, a lot of graduate students in art history I don't think they really relate that well to the artists, on a personal level. They often don't really know the techniques from having done them. I think it's wonderful when graduate students also take studio art so that they can get a sense of what's involved in actually making something. It's not that easy.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's not an object. As you said, you were able to identify the layers, the time, the gestation.

HARRISON

Well, it's also not just something that you study. It's something that was physically made by a human being and those people, they put a lot of themselves into it. So for me, that was a natural thing. It didn't bother me at all. I would be kind of appalled when some of my students would say, "Oh, you talked to the artist. Like, you know, what could you possibly learn from them that I'm not learning from my theoretical ideas." And it's like, give me a break. Let's get real here. But I think more students do actually do both now, which I'm glad of. But there's a kind of sympathy, I guess, that I got from that. Also, just I guess the ability to look at art for what it is, not the theoretical side of it, but just to appreciate for what it is. Of course, I'd like to know what the artist was trying to accomplish if there is a meaning on that level. But I'm more interested in the visceral response, the actual engagement with the work itself. I have pretty Catholic taste. I like abstract art. I like figurative art, too. But I don't feel like I have to choose. I can respond to whatever I feel engaged with.

This is an excerpt of a 7,000 word interview that will be published across our network of university journals in the coming weeks.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this podcast was Emma Veon. Assignment Editor was Sorella Lark. Digital Media Coordinator is Camille Montilino. “Winter Time” was composed by Nikolas Anadolis and performed by the Athenian Trio.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process.