EXCERPTS

THE IMPORTANCE OF INTERDISCIPLINARY EDUCATION

The reason I think you should read in these other disciplines is because it will help you in your own work. Now I really mean that. I think what has happened with the fragmentation of disciplines is that when problems arise. ...the people working in the discipline are unable to see avenues out of the problem that they would easily see if they had worked through problems in other disciplines.

–SIRI HUSTVEDT

Novelist and essayist

❧

Curating has to do with junction making, which is what J.G. Ballard defined when I met him, the great English writer. And I think, in a way, when I wake up in the morning, I always think how can I bring people together? We haven't met each other yet. And I think my activity has always to do with junction making.

I mean, when I do exhibitions, I make junctions between artworks. I make junctions between artists. I make junctions between art and different disciplines because I think we live in a society where there are a lot of silos. There are different very specialized worlds. And I've always seen it as my role to make connections between these different worlds, make junctions between these different worlds. And I think, if we want to address the big question or challenges of the 21st century–if it's extinction and ecology or if it's inequality or if it's the future of technology–I think it's very important that we go beyond the fear of pooling knowledge. We go beyond these silos of knowledge and bring the different disciplines together.

–HANS-ULRICH OBRIST

Artistic Director

Serpentine Gallery

The World Heritage Centre was created on the first of May 1992, and it brought together the two parts of the World Heritage Convention and the Secretariat, meaning the natural heritage and the cultural heritage which were previously in two different divisions. It's a very unique instrument. It has now 193 countries, which have ratified it. The idea of this convention is really unique because it is about heritage of outstanding universal value, which is to be preserved not for us, but for the generations to come. And that idea came together in 1972 when we had the first International Conference on the Human Environment. The first UN conference on this. And it was quite interesting. It was a time when you had many NGOs. It was after the publication of a book which was called Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. And it was the idea that there are so many threats to this amazing heritage that the whole of the international community has to do something.

–MECHTILD RÖSSLER

Director

UNESCO World Heritage Centre

This museum, this institution has a long history and actually, the idea of a museum goes back to maybe 100 years ago when Civil War veterans wanted a monument recognizing the service and the sacrifice of African Americans during the war effort. And over the years in the 20th century had the support of Congress but nothing ever really came of it, and it wasn't until the mid-late 80s when congressman John Lewis with some other colleagues started to bring forth the idea that the Smithsonian needed to have a presence to recognize the significance and contributions of African Americans to the history of this country.

–DWANDALYN R. REECE, Ph.D.

Acting Associate Director for Curatorial Affairs · Curator of Music and Performing Arts

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Smithsonian Institution

❧

I think that contact with ancient civilizations is very important because we get to have in our life a third dimension. If we live only in the present, we don't understand what happened many thousand years ago. We don't realize what the development of humanity really is. I think it's very helpful to know history. I don't believe that history can teach for the future, but history can give us another dimension, can make us wiser with more abilities to judge our present.

Sometimes we think that we invented everything, but this is not true. The history of human thinking is very important, is very useful for us to know different thinking of other people. At the end of the day, multicultural civilisation is also very helpful today. I know, for myself, I concentrate on antiquity, but sometimes I work on on other civilizations. Some months ago I organized an exhibition on a very famous Chinese emperor – Qianlong (1711-99). And through this opportunity, I studied a little about Chinese culture, and I found very exciting things. And I can compare these things with our Western civilization. All this is very fruitful because we open our eyes, and we are not going on only one track. There are different approaches in life and different interpretations of the world and of societies.

–Professor DIMITRIOS PANDERMALIS

President of the Acropolis Museum

There's something about a tangible artifact that people love. And I think we should trust humanity and trust people a little bit more. Certainly, there are people who are willing to just abandon the physical artifact – whether it's books or anything else – and just live in a virtual world. But I think more of us appreciate the tactile experience of being in the world, and that's the one thing that we should never forget.

As seductive as the virtual world can be – where there are fewer boundaries, where you can be anything, and you can be anyone – there's something very important about the tactile world and being grounded in the tactile world. And so far humanity has not lost sight of that collectively. And I do not think that we will.

–ROXANE GAY

Writer

❧

When I look at a film, I normally think what is missing from that, and that's what I'm trying to bring. I'm trying to find something that I think isn't there and that I could bring that would make it more interesting, make it more cinematic, more dramatic.

I like just making things up, but music education for children, at least in this country, doesn't typically involve that. They don't have classes in improvisation or music theory for young kids.

I don't really understand why. So my musical education just completely killed any interest in music I would have had. It was only later when I was a teenager a friend showed me a little bit about improvisation on the piano and that got me back into playing and that's why I'm doing this now. It was very therapeutic as a teenager, as an adolescent just to sit at the piano and just express things that I couldn't express in some other way.

–CARTER BURWELL

Film composer

Carol; Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri; Millers Crossing; Being John Malkovich, True Grit...

❧

They are very different skill sets and very different ways of approaching storytelling. Writing is very private. I find writing to be very difficult. I have an idea. I have a feeling, and then I write into it. That part of the process is the most painful and the most demanding. Directing is easier. It’s a very different skill set. It’s applying a story to the technique of how you film it, how it’s going to work. That part is so simple. The writing is brutally hard. There’s an architecture to every season that you write in television. I have to see the whole story. This big twelve-hour story. There’s a lot of math in that. There’s a lot of Where am I going? and How is it going to feel? Because at the end of the day, all I’m doing is trying to make people feel something.

–DAVID HOLLANDER

Showrunner, writer, director, producer

❧

My early musical memories have to do with nature. That has also has to do with what I selected in my memory, and a show like The Affair, which is all about that and how people are...how their recollections of something are always going to be different, even if they themselves remember now and remember a few years from now, but certainly between characters. And I find that what really works on The Affair is trying to build a sense of introspection in the music. We've become pretty good in the show at really getting to that place very fast, and I think the music, the way that it's shot, and the way that it's written, of course, all work in conjunction. There’s something about a passage of time in your mind. Then it's not about the clocks. It's more about the suspended, almost like the absence of clocks, and the idea of suspended time, which memory is more like that since in our memory all time happens at once. Everything is happening at once...I think that the key remains in having love for those characters as you're writing them and not judging them because it's not my place to judge. It's my place to illuminate what's in there without any kind of moral or personal judgment. So, if it's a monster, you have to embrace the monster and kind of love the monster, in a way.

–MARCELO ZARVOS

Pianist and TV/Film composer

❧

I think that what they don't realize often is that the skills of the people that are sitting in those jobs are deeply in conflict with the skills required to perform well in our our time. I think that that's what people were taught. How to be accurate. How to be quick. How to learn the software technology that allows you to do that even more easily, but the skills like listening, empathy, leadership, maintaining relationships, responding, recognizing good ideas and being vocal about that–there are so many little pieces of culture that are required to make a network-based world continue to function and for people to be successful. And it seems like everything we were taught in our large American school system was basically the opposite. And so, I think there is an enormous amount of change that needs to happen in education. And I think, in some instances, it's beginning to, but we're really working and teaching our future using systems that are antiquated and don't really relate.

–ITAMAR KUBOVY

Executive Director

Pilobolus Dance Company & Five Senses Festival

❧

The whole thing is to get them to feel like no matter where their background is from, the difficulty they have in their personal lives, the isolation that they feel in relationship to that, that within the art community they are embraced, they are welcomed. All they have to do is just keep getting better at it, but the community is there. I think that something we're all looking for is where we belong.

– ERIC FISCHL

Artist

The Great White Hope, well that was just a remarkable piece of history and theater and film to be involved with for so many years. 1968 was a year of amazing political tension and movement in the United States. It was the height of the Black Power Movement. There was a wonderful black leader named Stokely Carmichael who was promulgating Black is Beautiful and Black Power. For our careers, it was seminal. Both James Earl Jones and I received Tony Awards and then we received we went on to do the film. We both received Academy Award nominations. That kind of set us up for our careers because both James Earl and myself went on to do not only film, television, but continued to be prominent in the theater as well. We felt extremely fortunate that happened.

And I did not seek out these roles, but All the President's Men…I know that I was very interested in social and political issues from childhood. I grew up in a family of Republicans. A medical family. And I swear I came out of my mother's womb as a Democrat. I was liberal from a very early age! And I just remember arguing with them at 10 years old and saying, "No, no, but you have to think about this! And that!" But the truth was I don't know whether there was something in me that translated that I was politically and socially conscious when I was a young actress because these roles came to me. I didn't go out begging for them. And I was so grateful to have them because I thought they had a depth to them.

And I never thought for a minute that I would become the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts because I didn't have any background for that kind of political position, but I met with four people who were very influential in New York that the administration had asked to vet me, besides the FBI just talked to me about what I could do culturally for the agency. And they made it clear they just wanted the First Amendment - Freedom of Expression upheld. ... So, I said, well, yes, of course. I'm an actress, and nothing human is alien to me.

–JANE ALEXANDER

Actress, conservationist, chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts 1993-97

❧

When I was growing up and studying to be an actor as a young man, I'd read plays that were most often based in New York City. A lot of the writers came out the New York writing school, per se, and while I could understand it and relate to it and growing up in Chicago it wasn't that difficult for me to somewhat decipher the nuances of that, but when I read Mamet, to me, it was almost like–Yeah! I get it. This is a language I understand. It felt very comfortable to me. And I know he has told me that he has written characters with my voice in his mind as he wrote them, and so, again how lucky for me that that's the case, so it would at least make sense that I would have a certain degree of comfort and familiarity to that kind of Mamet-speak, whatever it may be. I feel very lucky that it's worked out that way that he's the writer that I ended up hooking up with.

–JOE MANTEGNA

Actor and director

❧

After all, the Trojan War is a mythical war. It's a fragment that has been painted upon by generations of artists. It is fictional. It's a profoundly fictional work that has formed the Greek people, just as the Gospels are works of fiction. We have no historical accounts of Jesus. We only have artistic accounts. It's interesting to me that the West has been shaped by two works of fiction, The Iliad and The Odyssey and the Gospels, which are prehistoric artistic works. The West has two feet. They're both fictional feet, and after that we started being rational and reasonable.

–YANN MARTEL

Novelist

❧

Libraries can be the lifeblood of communities. In my little hometown, Northfield, Minnesota, I started going to the local library...and I loved it. I remember going there. I remember the smell of the books, the card catalog. I remember the excitement of checking out books. I remember the reading group I belonged to as a very small child. And the whole atmosphere, the excitement...

...my father was a professor. And he would take my sister and me along with him while he worked in the archives...And we often drew or read on the floor, but the feeling of the library, which then was of course associated with my father, and my affection for my father ran deep.

–SIRI HUSTVEDT

Novelist and essayist

Portrait of Cynthia daniels by mia funk

❧

There's a great song. It's called "A Quiet Thing" and it's by Kandor and Ebb who wrote "Cabaret".

The lyrics are–

When it all comes true

Just the way you'd planned

There are no trumpets or parades

It's a quiet thing.

So, you see, by the time you win a Grammy, you've probably been working for twenty or thirty years. A lot of us. Many people are of course young and get their overnight sensation, but most "overnight" sensations are a lifetime achievement. That's why I did it quietly. I ate some popcorn and called my mother and then regretted that I didn't go do it.

–CYNTHIA DANIELS

Music producer and sound engineer

❧

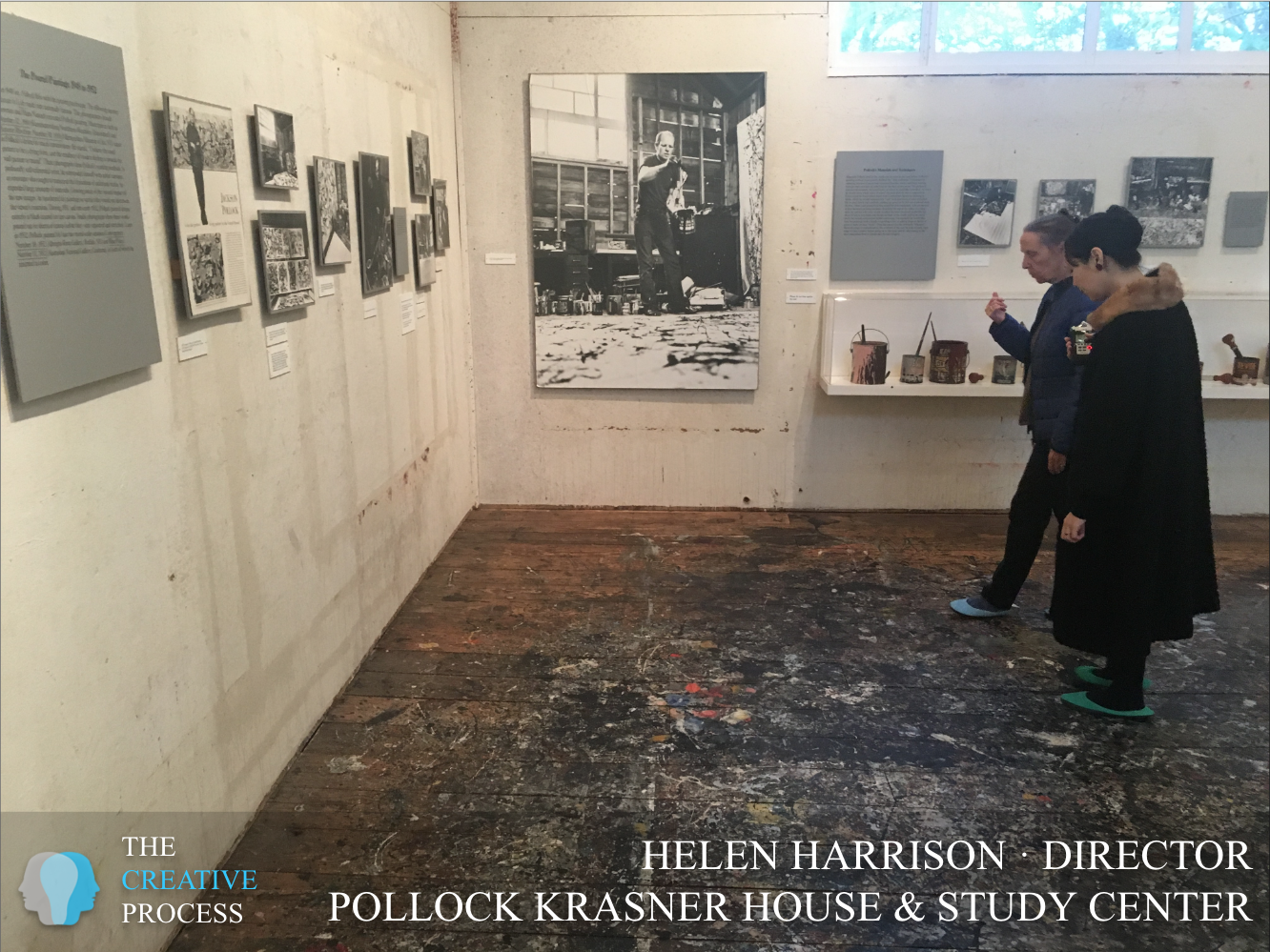

Jackson Pollock said it himself. “It's energy and motion made visible.” So these are things that come spontaneously from his own feelings, but they're based on, first of all, observation, the natural world around him, all the forces of nature that were so influential. And then, processing that and figuring out how to create a visual language that expresses those feelings. And some of those feelings can be very complicated. And the technique, the means of expression is dictated by what those feelings are. It's not the other way around. People think – Oh, he used the liquid material and then he sort of danced around and that kind of gave him ideas. – No.

–HELEN HARRISON

Director

Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center

I've kept journals all my life in an attempt to write about how I'm working, what I'm working on, how it's going, hoping to be able to enhance my creative process. It's interesting that you call your show The Creative Process because these are two words that are constantly in the foreground of my concern...

Whatever I do, quite often I say– Is this good for my work? Should I go here? Should I do that? When I had my initial debut, I became known for a book called The Somnambulist. I took 24 of those pictures in one weekend and then I worked for three years on the next 24.

–RALPH GIBSON

Photographer

❧

IN MEMORIAM ROY LICHTENSTEIN

People think those Pop paintings are kind of funny. Well, maybe. Or that he was a comic artist in some way. He is in some way. But as far as I knew and know him, all his life he was deeply, deeply, deeply an artist. He believed in it, without ever pontificating. I mean, he was really part of the conversation without ever expressing it. Without ever talking, he just did, did it, did it with a sense of the reach into art history. I saw that he was in a line of continuity. If you look at the work, you see how so much of it is a discussion with art. With surrealism, with cubism, with futurism… Capture the style, and then bring it to another place. Bring it to another dimension. Absorbing it, capturing it, synthesizing it, and then saying a little bit more. I think he's a really great artist. Not just a good artist and a wonderful artist, but a great artist. I think he's in the line of continuity, he belongs with that line that goes to Giotto to Poussin to Cézanne to Picasso. I miss him terribly. It was a great relationship.

–FREDERIC TUTEN

Writer

❧

The difference is vast, but it's the same root. It's just some of the techniques are very different. I really know theater because that's where I started. I went at it in a very haphazard way. I had a very haphazard approach. It was not orderly at all. I didn't go to a proper school or anything like that. After fooling around in Europe for almost a couple of years, just because I'd gotten out of the army...and didn't really know what to do or how to do it. And so I just went and while there I did some acting, but nothing very remarkable except doing a nightclub with William Burroughs. That was great fun. I did a little bit of studying here or there...Jeff Corey (and at one class in New York) someone said something that helped me a great deal. And then I just learned by doing it.

–HARRIS YULIN

Actor and theater director

❧

When I first started acting and came to Los Angeles for a one week job. I was with my dad and we went to a production of a play called Fences. And James Earl Jones was the star. And I remember I was just the whitest kid ever from small town New Mexico in this big city of Los Angeles, which isn't super diverse, at least it didn't feel that way. And then I'm sitting there watching this play about a lower middle-class African American man in Pittsburg and his family. And I just remember being so moved, moved to tears at thirteen, fourteen years old about a world that I really knew nothing about. Not even from school, even, but certainly not this feeling empathy for this specific man and wife, and she was peeling potatoes on a rocking chair and monologing ire at his character and it was so moving. And I did think, even back then I recognized the impact that the theater can have on someone that isn't even anything like what they're like.

–NEIL PATRICK HARRIS

Actor, writer, producer, magician, and singer

So, in a way, art becomes a kind of permanent record of human experience in the way that no other phenomenon can. And that's why we have to continue to pay attention to it, at our peril. And, in terms of improving the study of art and integrating it even more richly into our lives, I do think that we have to examine the canon as we perceive it. Because the canon has been controlled largely by white men, white American and European men who have determined what is worthy of study and what is not.

And I think we have to look to find the voices of women and marginalized people because sometimes it's the most disenfranchised people in the culture that are the most articulate about it and most aware of the innate injustice in certain social systems. So I think we really have examine our canon and broaden and deepen it to include more voices.

–DOUG WRIGHT

Playwright & President of the Dramatists Guild of America

❧

Digital technology allows us to communicate and use imagination in all kinds of ways, but I do think it has created a barrier for just simple interactions. I think it has sped everything up because we can access things so quickly...I think that has sort of an isolation which then compels this kind of commercial sublimation of isolation, loneliness, and human. Keeping people interested in dance is exposing folks, no matter how big or small an audience, to the different ways of seeing. How can you place a value on solace, joy, or tenderness and vulnerability?

–JILL JOHNSON

Dancer, choreographer and ballet stager

❧

Décimas is one of many stanzas in Spanish poetry, but it's a very special one because it's very old. It comes from the 1500s. And it traveled all through the different territories that the Spanish conquered. So, from Spain, it spread through all Latin America, from Mexico to the Caribbean to the point of Patagonia, but everywhere in a different way. And everywhere the tradition sort of at some point is connected to each other, so it became a very local thing. And everywhere you go, it's like the most traditional local thing is the Décima, but it's everywhere as well. It's ours, it's theirs, it's everyone's. And it's a very musical form of poetry, and it has been for now five centuries the media where folk poetry has lived and a lot of improvisation as well. Improvised poetry, which makes it an oral art form, not literature. It's like oraliture.

–NANO STERN

Musician and songwriter

❧

Yet in truth, the lives of most people have meaning only within the network of stories they tell one another. People are usually afraid of change because they fear the unknown. But the single greatest constant of history is that everything changes. Each and every one of us has been born into a given historical reality, ruled by particular norms and values, and managed by a unique economic and political system. We take this reality for granted, thinking it is natural, inevitable and immutable. We forget that our world was created by an accidental chain of events and that history shaped not only our technology, politics, and society, but also our thoughts, fears and dreams.

–YUVAL NOAH HARARI

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

Courtesy of the author

❧

As a writer, I am not satisfied with sentences such as “I was feeling very anxious” or “she felt overcome with joy.” I want readers to experience anguish, joy, feelings, and events. I also want them to feel mounting tension or suspense. I believe that following a narrative is a very intense experience, immersive on a mental as well as on the physical level. Reading is for me just as powerful as writing. I spend three hours a day reading, the rest of the time writing, and in between, I try to live in the best way I can.

–MARIE DARRIEUSSECQ

Novelist

❧

Creativity is perhaps the ultimate mystery. I veer wildly between opposing views on it and have different feelings depending on whether the creator is isolated or a collaborator. Gropius said the artist is an exalted craftsman. “In rare moments of inspiration, moments beyond the control of his will, the grace of Heaven may cause his work to blossom into art, but proficiency in his craft is essential to every artist. Therein lies the source of creative imagination." And Steve Sondheim said, "Art is craft, not inspiration." And Rilke mistrusted any artist's knowing participation in his own creative process.

–TONY WALTON

Art and theater director, costume designer

I’ve always, pretty much from the beginning, I’ve always wanted to write as if I were paying by the word to be published. So that’s always gone in there. Whether it’s film or television, whether it’s comics, whether it’s novels and especially short stories. I want every word to count.

- NEIL GAIMAN

Writer, graphic novelist, producer

So that idea of what the drawings tell us about the artist is another thing that's constantly interesting to me. You, maybe more so than a finished painting, get a sense of what problems an artist is trying to work out along the way. What ideas he has and rejects sometimes tell you an awful lot about the choices made in the final work. I like that insight into the creative process that you get from studying drawings.

–JOHN MARCIARI

Charles W. Engelhard Curator and Head of the Department of Drawings and Prints

The Morgan Library & Museum

ON 100 YEARS OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

Women just generally don't get acknowledged, period. We're still grappling with that. And we never got the Equal Rights Amendment passed, and we're just now really making a big fuss with Me Too about how long we’ve endured harassment and diminishment. How is that even possible? I was in a group called the Women's Action Coalition in the early 90's. The fact that we couldn't get the ERA passed is insane. Although, now as I’m seeing it reintroduced, it should be a true equal rights amendment for everybody. Not just focused on women being equal to men, but a real update to the constitution. We still have things that we need to rewrite.

–APRIL GORNIK

Artist and activist for people, places, and animals

❧

I was born in 1942 in a Catholic, conservative, patriarchal society. And I was born angry against the world as I saw it. I became a feminist before the word reached Chile. I was a young girl when I realized I didn’t want to be like my mother, although I adored her, I wanted to be like my grandfather and the men in our family: strong, independent, self-sufficient, unafraid. Later I learned that some women could be all that and decided I was going to be one of them. Since then I have worked with women and for women all my life. I have a foundation whose mission is to empower women and girls. I don’t need to invent my feminine characters, the women I have known inspire me.

–ISABEL ALLENDE

Novelist, feminist, philanthropist

I actually assumed in graduate school that I would become a teacher and I've taught in a number of different universities, but it was working with art objects and seeing them in museums like the Metropolitan Museum or The Frick that made me want to go into museum work and ultimately become a curator. So when I was finishing my dissertation and had to think about a career, I applied to a lot of teaching jobs and there was one job that year in America in my specialized field, which was European sculpture, and I was very lucky. But a professional career is a bit of luck as well as predisposition, so I knew I wanted to work in museums, and I was lucky enough when

I was able to find my way here.

–IAN WARDROPPER

Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Director

The Frick Collection

❧

I guess the part that's our thing is the method or process that Renée Jaworski was describing. The constraint, the framework that we try to put on what we're doing includes that, for this time, let's not map everything out first and try and realize the vision that one person has but to put people together, as Renée was saying, and have something else emerge that's a product of everybody that's involved.

Penn Jillette, who we were honored to work with, the way he put it is, "You're not a collective, you're not looking the same, talking the same, you don't use the same terms for movement. All the dancers look different, and they think differently as well."

–MATT KENT

Co-Artistic Director

Pilobolus Dance Company

❧

I always say they are almost like bellwethers. They pick up on trends, pick up on anxieties, pick up on things in the world almost before the rest of us do. And artists get up, eat their cornflakes, go to work. They really do. And it's this creative process, which as Chuck Close once debunked and said, "Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us get up and work." It's not always inspiration, but another great quote of his is that he always, anytime he sees a lot of painting like going to a museum, he's always astonished by the transcendent moment when you realize that this is just colored dirt and pigment laid on the surface with what's arguably just a stick. There's such a metaphysical moment when these images are created on a surface. In three dimension on a flat surface, it's kind of a head-scratcher to start. So great art has a transcendent moment.

–ALICIA LONGWELL

Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chief Curator

Parrish Art Museum

In Lisa Phillips' case, she really wanted to move into the future as quickly as possible, and everything was indeed a move in that direction. So that became our rallying cry there is that when you're looking, really look very, very hard at the new. Look very very hard at what challenges you. If you're bothered by it, go deeper. So it was "Don't take the easy way out and say 'I love that'. 'Why do you love it?' 'I just feel it.' No, unacceptable. Just feeling it is not enough, if you're a responsible party. If you're a member of the public, fine, have whatever kind of experience you want, but if you're a professional, know why you're doing it.

–RICHARD FLOOD

International Leadership Council, Ideas City Initiative & Former Curator at Large

The New Museum of Contemporary Art

❧

It's about, can you handle the complexity of these things and, with American Indians, it's overwhelming for the American public, this terrible tragedy and seeing Indians as part of the 21st century. Seeing Indians who are engineers or contemporary artists at biennials is hard for people because they're coming from a place of guilt and also not knowing how to process things. And so to always see Indians as of the past, which is sort of what happens. We're only Indian as much as we're like our ancestors is something the museum has always been trying to challenge. And, you know, it's difficult. This is not a good time for complexity and nuance. We're trying to flip the script from the idea of just tragedy, this terrible past, to say–American Indians are part of the 21st century doing all kinds of interesting things. And the connections between American Indians and the United States are profound and deep. And it's not simply an issue of us being victims and the U.S. being the oppressor. It's much more complicated than that.

–PAUL CHAAT SMITH

Associate Curator

Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

If you create the conditions in which people feel comfortable interacting with art, there are some really beautiful things that can emerge from that encounter. Things that I think are life changing. And so that’s why I enjoy it. When I was at school, we were told that we could do absolutely anything what we wanted to do. Anything whatsoever. There were no barriers. None. And probably it made me the person I am today.

I always thought that I could do exactly what I wanted. People also say, in terms of FIAC, that the fact that I am a foreigner has helped me because it’s true I don’t feel burdened by convention because it’s always been done that way. I feel completely unfettered and I don’t feel bound by convention and the aim is to federate the cultural world around the events. I am not going to create upset gratuitously, but if I think something can be done differently and better, then I will definitely do it.

–JENNIFER FLAY

Director of FIAC

Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain

❧

I do develop my books in scenes, and write a lot of dialogue – though book dialogue is different from stage dialogue, which is different from TV dialogue – and that is different from radio dialogue – I’ve explored all these facets. I think I am covertly a playwright and always have been – it’s just that the plays last for weeks, instead of a couple of hours. An astute critic said that A Place of Greater Safety is like a vast shooting script, and I think that’s true. It shows its workings. When I am writing I am also seeing and hearing – for me writing is not an intellectual exercise. It’s rooted in the body and in the senses. So I am part-way there – I obey the old adage ‘show not tell.’ I hope I don’t exclude ideas from my books – but I try to embody them, rather than letting them remain abstractions.

In my reading of him, Thomas Cromwell is not an introspective character. He gives us snippets of his past, of memories as they float up – but he doesn’t brood, analyse. He is what he does. But that said, you are right, he is at the centre of every scene. With the weapon of the close-up, it was possible for Mark Rylance, on screen, to explore the nuances of his inner life. He is very convincing in showing ‘brain at work.’ He leaves Cromwell enigmatic but - in a way that’s beautifully judged – he doesn’t shut the viewer out.

–HILARY MANTEL

Novelist and memoirist

❧

We all inhabit interior landscapes & these are mediated to us through language. It might be said that we are the thoughts we are thinking. What engages the writer/ poet is the individual’s response to the “situation”—what she or he makes of it. That is the essence of the human drama, & why imaginative literature is so much deeper, more intense, & more memorable than objective history with its impersonal perspective.

–JOYCE CAROL OATES

Novelist, short story writer and memoirist

❧

All artists are seeking to create a modified world that conforms to their emotional and artistic expectations, and I am one of them, though, of course, as we grow and age those expectations are continually in flux. [...] Yes, like all of us, I have experienced disillusionment with the limits of human life and understanding. Perhaps, because I live so intensely in the imagination, this has hit me harder than most––I really can't say. But the mythos that underpins all societies is transparent, and that transparency, once seen through, is crushingly disappointing. I wish we were more than animals, I wish goodness ruled the world, I wish that God existed and we had a purpose. But the truth, naked and horrifying, stares us down every day. Ideals? What do they matter in the long run? What does anything matter? As I point out in the preface to T.C. Boyle Stories II, I went (at age twelve or so) from the embrace of Roman Catholicism (God, Jesus, Santa Claus, love abounding) to the embrace (at seventeen) of the existentialists, who pointed out to me the futility and purposelessness of existence. I've never recovered.

–T.C. BOYLE

Novelist

❧

When you're meant to be a writer, these things all impact your talent, so I've always felt the good part of that, there's no really good part to having parents like that, but writers can take stuff that happened to them and make something out of it. And I know that I got this ability to go back and forth between sadness and happiness within one piece of work, and I think that's because when I was eleven my life had, really forever after eleven, it just changed what my talent was from sunny to both sunny and painful, that I can combine them. So the great thing about being a writer is you can take the pain of your life and make something out of it. And you can mix it up with the happier parts and make something even better out of it. I mean, it's kind of all these things end up being gifts when you're older.

–DELIA EPHRON

Author, Screenwriter and Producer

❧

The thing is, our culture has started to think about writing and the humanities as if they are peripheral and negotiable – just a dusty sideshow set up alongside the real project, which is making money. But the only way people move toward freedom is to come to some understanding of what is enslaving them, and that, in essence, is what the humanities are: a controlled, generations-long effort to understand and defeat what enslaves us. So we marginalize that process at our own peril. That process is (and has always been) important to cultures.

–GEORGE SAUNDERS

Writer

Much art today is not connecting seeing to feeling. And that’s the big problem. It’s connecting seeing to seeing, and it’s also connecting the already seen to seeing. Usually, the artist is the one who is gifted to see first. Everyone witnesses, but the artist sees at the same time they witness. And it is the seeing that is the order of understanding. And so what you’re getting now is a lot of artists that are receiving already seen things. They’ve already been organised. And they’re taking it and they’re reorganising it. Maybe as a formal exercise, but not something that is really transformative.

–ERIC FISCHL

Artist

❧

I've been at the museum for 10 years, and when I came to this job all I was told was that I was going to develop this music exhibit and then "just go!" There was no concept brought to me or framework about how the exhibition had to be, so I really had an opportunity to take my experience as a scholar and working in museums to craft something that really reflected the totality of African American musical expression but also put it into a social and cultural and political context. Because what was important to me was not just the music itself but its significance in American history and from a global perspective. And with anything that I do, I'm very interested... museums tell stories with objects, so in many ways, I find myself a storyteller, and in the work that I do, I always want to be as comprehensive and inclusive as possible.

–DWANDALYN R. REECE, Ph.D.

Acting Associate Director for Curatorial Affairs · Curator of Music and Performing Arts

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Smithsonian Institution

❧

It was a long journey because I think I've been writing television now twenty-five years. I never really had the directing bug. I always loved writing and I like being behind the scenes and, in television, writers have so much control anyway to rise up the ranks and run the show and hire the directors, so I mostly had just great collaborations with directors. Especially on Sex and the City, we had really filmic talented directors and it was like one plus one equals three, I felt, collaborating with the directors, but there was a film that I was hired to rewrite. At the time it was called Whatever Makes You Happy that became Otherhood. And Mark Andrus (who won an Oscar for his script As Good As It Gets) had done the first adaptation, which I loved, so when I was hired to rewrite it, I thought why are they messing with this? I just want to protect what I love about it.

–CINDY CHUPACK

Writer, producer, director

Sex and the City, Modern Family, Everybody Loves Raymond, Otherhood

❧

I think for those who have crossed borders––the artificial beginning is interesting to me. There is a clear-cut: old life, that's old country, and here's there's new life, new country. It is an advantage. You are looking at life through an old pair of eyes and a new pair of eyes. And there's always that ambivalence––Where do you belong? And how do you belong? And I do think these are advantages of immigrant writers or writers with two languages or who have two worlds.

I think I might be an old-fashioned writer. People often comment that I'm a 19th-century writer. And I think maybe it's true. I think there are different ways to look at the world.

–YIYUN LI

Novelist and memoirist

❧

Looking back on the books in a retrospective overview, I've written a number of short stories from a first-person POV but I guess with novels I felt that this was too restrictive. What worked for me was a third-person approach that was somewhat suffused with the personality of the character. So I'd be free to describe and note things that my characters would not necessarily be describing or noting, but the emotional texture of the prose would be coloured by their attitudes and limitations. It was important not to switch suddenly from one sensibility to another, as this would have called attention to the art as well as possibly causing confusion. So, I used action-free, dialogue-free connective passages as a way of smoothing the transitions from one character's reality to another's, to give you time to adjust to no longer getting emotional cues from the character you'd been with. As soon as I judged that you would feel yourself to be on "neutral" narrative ground, ie., no longer in the spirit of a particular character, I would then take you into the sensibility of the next character.

Creativity is wonderful and comforting. I don't know if fiction writers are more spiritual than people who enjoy gardening or who run soup kitchens for the homeless. Any activity which asserts that there is some point to making things happen, despite the inevitability of death, decay, the vanishing of empires and the eventual extinction of our solar system, is spiritual, don't you think?

–MICHEL FABER

Novelist

❧

[on the line between fact and fiction in his memoirs.] In a way, I sometimes think that it’s when the divergences from what really happened are quite small that it calls for the services of a very scrupulous and clever biographer. Certainly the stuff you get about me from my books it’s not–how can I put it?–it’s not reliable as evidence in any court of law. I’m very conscious that I’m not under oath when I’m writing.

[on his biographical writings on writers and musicians] I remember a line from an essay of Camus’ where he talks about “those two thirsts without which we cannot live, by that I mean loving and admiring.” And I feel that I have zero capacity for reverence, but I have a great capacity for loving an admiring.

These are questions that interest me very much. You know there are certain particular times when certain books can be written and it’s very important to realize, you really can see, Well, I should have done that back then. One the striking things about going to places, there was that brief window when I went–Oh wow, suddenly it’s going to be possible to visit Leptis Magna, the greatest roman ruins on earth. And it turns out that was a very, very brief window.

–GEOFF DYER

Novelist and essayist

❧

And then meeting somebody like Mindy Kaling who is a total fashionista, where I got to do storytelling through clothes, but I also got to play fashionista and design contemporary clothes and gowns for the red carpet. And then, even through The Mindy Project, I designed a line of jewelry for BaubleBar and I designed a line of coats for Gilt, so I've gotten to play fashion designer in that same sort of way, but with a nod towards costume design. But I think that every day we get dressed up we're telling a story. I'm happy today. I'm sad today, so whether you're telling a story for the people at work or you're telling a story for your character on camera, I think that we tell a story every day by what we wear.

–SALVADOR PEREZ

President, Costume Designers Guild

The Mindy Project, Pitch Perfect trilogy, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Veronica Mars

❧

I sort of think we’re all kind of a swirl of everything we’ve read, the art we’ve looked at or heard, the life we’ve led, the people we know, the stories we’ve heard, the stories we’ve lived through and the stories we’ve heard secondhand, the fears we’ve had, the desires we’ve had, it’s kind of just swirling around, so when you’re writing it’s not that you’re channeling it in a completely unthinking way, but when I write I’m just sort of moving fence to fence and seeing what bubbles up and then I can shape it in the editing process and make it into what I want, but in the beginning I’m kind of feeling my way through so all those influences, whether they’re literary influences or life influences or influences from other arts are just kind of pulsing through me.

Gordon Lish taught a seminar that I attended for two or three years. When I published a few pieces in his magazine,The Quarterly, which he was editor of in the late 80’s into the 90’s, I was just bowled over by his ability to hear what I was trying to do and to see and suggest better ways to do it. Also, point out moments where he thought I was strong and moments and where he thought I was kind of falling away. He taught me a tremendous amount. One of the greatest things he taught was how to listen to yourself. You can be your own Gordon Lish.

I think that’s the misconception about Gordon. That’s what he did for Raymond Carver because that’s what he thought Raymond Carver’s stories demanded, that’s not what he thought everything needed to be. There was a period when lot things were like that, but the larger thing was about actually just not evading whatever it is you’re writing about. It wasn’t necessarily about compression or stripping down or being minimalist. It was about not evading your objects. Well, it was about being a writer. It was about teaching yourself not to run away from what you want to write about.

–SAM LIPSYTE

Novelist

❧

You know, years ago, I wrote a thing called A Writer's Prayer. [...] in about 1989, when I could see there were two futures.[...] "Oh Lord, let me not be one of those who writes too much, who spreads himself too thinly with his words. Diluting all the things he has to say like butter spread too thinly on a piece of toast, or watered milk in some worn out hotel. But let me write the things I have to say, and then be silent ‘til I need to speak. Oh Lord, let me not be one of those who writes too little. A decade man, between each tale, or more, where every word becomes significant and dread replaces joy upon the page. Perfection is like chasing the horizon, you kept perfection, gave the rest to us. So let me know when I should just move on. But over and above those two mad specters of parsimony and profligacy, Lord, let me be brave. And let me, while I craft my tales, be wise. Let me say true things, in a voice that's true. And with the truth in mind, let me write lies."

[...]

When I was about 5-years-old I saw the Mary Poppins book and it had a picture of Julie Andrews on the cover and I got my parents to buy it for me and I took it home and discovered that Mary Poppins was so much darker and stranger and deeper than anything in Disney, so I may have read it as a 5-year-old hoping to re-experience the film that I remembered having loved, but what I found in the Mary Poppins book which I kept going back to, was this sort of almost Shamanistic world, a world in which Mary Poppins acts as a link between the luminous and the real, the idea that you're in a very real world, you're in this London, cherry tree lane, 1933, except that if you have the right person with you, you can go and meet the animals at the zoo. You can go to the stars and dance with the sun, you can, you know there's, you can watch people painting the flowers in the spring, just, it was very, it was deep. You know, Mary Poppins is very smart and deep and weird and P.L. Travers was smart and deeply weird and writing smart, deep, weird fiction. The Narnia books–running intoNarnia–while I loved the stories I loved what he did to my head even more. The idea that anything could be a door, the idea that the back of the wardrobe could open up unto a world in which it was winter and there were other worlds inches away from us, became just part of the way that I saw the world, that was how I assumed the way the world worked, when I was a kid that was the way that I saw.

–NEIL GAIMAN

Writer, graphic novelist, producer

❧

We’re all making decisions all the time and in the process of those decisions, a lot of them at that moment not quite clear to us which is the good and which is the bad decision. Right and wrong, we’re kind of navigating in the fog all the time [...]but the sum of those decisions as we go on is who we are, so I’m very interested in the process by which people createthemselves by this constant act of deciding and doing this thing rather than another thing. I don’t start off to create a moral in telling a story, but there are certainly consequences to the decisions that we make and some of those will no doubt have what we call a moral dimension to them. I don’t respond very enthusiastically to fiction that I can see that sum on the scales and I can see that it’s a sermon in disguise, if you will. I’m more interested in writing that explores rather than proclaims.

–TOBIAS WOLFF

Novelist, short story writer and memoirist

❧

One of the last plays that Peter Boyle did, we did a production that Tony Walton directed, which was Moby Dick Rehearsed. Tony directed and Peter played Ahab, and that was one of the first big plays that we did here back in 2005. There were a handful of plays we did before that. There's posters on the walls. When I got here, I started to do some of the Shakespeare plays, working sometimes with kids from the community and professional artists. Michael Nathanson played Hamlet with us in 2005. Alec Baldwin, Eric Bogosian, Jeffrey Tambor, Anne Jackson and Eli Wallach, who lived in East Hampton about two blocks from here. They were involved in the John Drew Theater from the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Through much of their lives, they were lifetime performers at Guild Hall, always in the summer doing a little something. Eli worked up until his 90s, and he was still working, as sharp as a tack.

Laurie Anderson, Leslie Odom Jr. from Hamilton was here a couple of years ago. It was fantastic. Judd Hirsch. I got a chance to drive in my car with Charles Durning and Jack Klugman, and the two guys were in the back of my Toyota. Having studied at Circle in the Square, and worked in the city in the basement and been the hindquarters of Babar, and then the next surreal couple of years later I'm driving around The Hamptons with Charles Durning and Jack Klugman, who were two character actors that I admired all my life. It was a surreal experience.

There's been so many artists here. Two summers ago, Questlove was here interviewing Jerry Seinfeld on the stage and Alec Baldwin has been our board president for a number of years. He liked the renovations. He liked the show that Harris Yulin did with Amy Irving. He loved The Glass Menagerie and he loved the renovation. So he said, I want to get involved with you guys. And the next year he did a production of Equus that Tony Walton directed, and I was honored to produce. And he got excited about the theater a couple of years later. He did a big production of All My Sons that Steve Hamilton directed.

The Hamptons is a wonderfully welcoming place to make art. I think going back to the time of Jackson Pollock and before him the tile painters, this has been an artist colony. And I think there is still a spirit of that around.

–JOSH GLADSTONE

Actor and Artistic Director of John Drew Theater

Guild Hall of East Hampton

❧

My father was a businessman in Chile. He was running a mine for an American company. And this was during the time of Allende and they eventually nationalized the mine. But yes, he admitted to me, actually the night before I went off to Trinity, we were sitting in this Japanese restaurant downtown. My father was a very difficult guy, but there was this sort of[...] interesting Brooklyn charm to him and he got very drunk that night on saketini [...] and he suddenly came out with all this stuff, you know: ‘I've been working for the [CIA] down there.’ And I wasn't shocked or mortified or morally repulsed, I just thought, God, that's interesting.

[...]

I think you've struck upon something crucial. The humanities, culture, in real terms, cost very little and does so much. Culture is my passion. [...] Today, the book is very much menaced by the screen. One of the things we really need to do is get new readers. I feel very strongly that education is the most crucial thing in the world. Education subverts ignorance. Education allows people to think in a more nuanced way. Fundamentally, literature has no frontiers. Curiosity is a very underrated virtue and it’s so crucial. You have to be curious. You have to be interested. Curiosity is an essential thing in life. It keeps you young.

–DOUGLAS KENNEDY

Writer

❧

When I compare novelists to short story writers or very short story writers, I can’t compare them, but one thing for sure, the purpose is different. I think that someone who writes tries to create or document a world. And when you write very short fiction you try to document a motion, some kind of movement. It’s not even time. Let’s say if you try to draw a picture of, let’s say, a lake, you know? A lake and trees next to it, then this is like writing a novel. But if you, let’s say you know I throw a stone in it and I don’t want to draw the lake, I just want to draw the ripples in the water. So it’s basically, I think there is something I try to look for in a short fiction, that it won’t be encumbered by it. But you know, it won’t be physical, it will just be some kind of a... It’s like if I move my hand, then it’s like if you don’t draw my body, but you just draw... [Keret makes a movement with his hand]

[...]

When I grew up, basically a lot of the people around me spoke Yiddish. Both my parents spoke Yiddish and a lot of the other people we knew. And they would always tell each other jokes in Yiddish and laugh really, really out loud. And then I would ask––what is the joke?––and they would translate it to Hebrew and it wouldn’t be funny. And they would always say, “in Yiddish it is very funny.” So I always had this feeling that I grew up with an inferior language. That I was living in a language in which nothing was juicy and nothing was funny and that basically there was this lost paradise of Yiddish in which everything seems to be funny. So when I grew up and I started reading I always looked for Yiddish writers. Writers like Bashevis Singer or Sholem Aleichem because I already knew there is something powerful hiding under that Yiddish.

–ETGAR KERET

Writer and Film/TV director

❧

It is probably the most important thing I can think of. Especially when I think of two things. In terms of history, the humanities show was how we were, why we were, and while we were...But then I also think about the future. You know. What are we doing now? What seeds are we planting to inform the future...And I said it earlier about making sense out of a chaotic universe where bad things happen to good people. Arts will help you figure that out.

I do feel that we are infinite choice makers. You make millions of choices all the time. Make the right choice and if you make the wrong choice, understand that mistakes are great teachers. Learn from that and move on.

-SEÁN CURRAN

Dancer and choreographer

Chair of the Department of Dance at NYU Tisch School of the Arts

❧

I think part of what I was thinking about with this project was to build the fact that [my character] Yunior is a writer and that with Yunior being a writer we get to check in with his maturing and changing perspective, so that in fact part of the game of writing Yunior is the notion that he’s going to be quite different from book to book and also that occasionally I’m going to in This is How You Lose Her write Yunior from a perspective that’s a period that’s a bit far off from the period he’s writing. Therefore built into the story there’s a perspective that might not otherwise be available if I was writing far more closely to the events he was narrating. These are the weird nerdy decisions one makes as one writes where one has to decide the events that are occurring in your text. You have to decide what’s the distance between the event and the point of telling where the narrator stands, looking upon and reflecting and retelling those events.

–JUNOT DÍAZ

Writer

❧

I think it's all about the idea. You start from the idea. So many times when I'm explaining process to people, it has nothing to do with technical. It has to do with idea. The technical aspect is pretty easy because it's arithmetic, it's math. And then when you come up with a great idea then you're basing the outcome, in terms of the way that you perceive it or preemptively see it, rather than necessarily just go out and take the picture. So I try to work from an emotional aspect of the way that I think about a photograph, either through, I call it a wink, which is like giving it a sense of life and a sense of humor. Or just absolutely an emotional response from my viewer.

–MARK SELIGER

Photographer

❧

I think many of my stories work on this principle: everything is just as it is in our world (they physicality, the psychology, etc) except for one distorted thing. The effect, I hope, is to make the reader (and me) see our "real" world in a slightly new light. Kind of like if you woke up in a word where, every few minutes, peoples' heads popped off. But otherwise everything else was normal. What would that story be "about?" Well, it might be about, for example, our reaction to illness, or to trouble, or about coping mechanisms. And it would be about those things because, other than the heads popping off, people behaved just as they do in this world. A little like a science experiment where all of the variables are held constant except one. We are trying to look into the question of what a human being really is, and a story can be an experiment in which we say, "OK, let's destabilize the world in which this creature lives and then, by its reaction to the disturbance, see what we can conclude about the core mechanism.

–GEORGE SAUNDERS

Writer

❧

We have Leonardo in full when we read his texts because it's still there. It's a full testimony, but his private life, we don't know much about it, but he certainly must have been very well organized because you can't make so much work without a base in the organization of your life which is very strict. Andyou can't go and penetrate such high intellectual spheres unless you're a man of good. Do you understand what I mean? To have some ideal of perfection, beauty, and humanity inside yourself.

–JACQUES FRANCK

Painter and Art Historian, Consulting Expert for

Louvre Museum & Armand Hammer Center for Leonardo Studies at UCLA, among others

❧

Working on this project, I am often reminded of what Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote–

When you want to build a ship,

do not begin by gathering wood,

cutting boards and distributing work,

but rather awaken within men

the desire to long for the vast

and endless sea.

–MIA FUNK

Artist, Interviewer & Founder of The Creative Process

❧

I try to react how I would normally as myself, but then I also, you're inhabiting another person, another role, so it's a blend of the two and then it's just purely based on intention–what I'm trying to get across. And I wasn't very good at doing that in the regular rep ballets, but I find things aren't as tiring if I kind of go into that mindset when I'm dancing, even something like Emergence, even a Balanchine ballet where there is no story. I try to create something for myself. Especially, sometimes with coaching, we don't have the time to coach and you're just putting a ballet together, so I need something to help pull me through. I always do a lot of studying into the history of something, if I feel like that is going to help me. And then, if that's not going to help me, I make up a story. I do a lot of different things for each role and each performance, and sometimes when I repeat something something else will come through. So it really changes every single time.

–NOELANI PANTASTICO

Principal Dancer

Pacific Northwest Ballet

❧

I feel like anybody can make a church or a garden spiritual, but for me the more interesting thing is to see if you can make holy or spiritual things that are just very ordinary. I also think that’s kind of the truth. I think if God exists it’s everywhere, not just in a church. But in an ugly spot. In a spot where atrocities happen. There’s all sorts of places that are holy, not just the ones that are defined that way by the culture. That’s always been a part of my work. From the very beginning.

–DARCEY STEINKE

Novelist and memoirist

❧

Katherine Anne Porter, essentially what she says is that the arts are what we find when the rubble is cleared away. In other words, they are the sum and substance of our lives, and we can go through wars and changes and all kinds of challenges in the world, but in the end, the arts tell us who we are and they are what remain no matter what…

...And when we look back and understand other civilizations that went before us, and when we think ahead to how people will view us in future civilizations, it will be our art and the arts that inform that story and tell people who we are and who we were, just as they do now from history.

–EMMA WALTON HAMILTON

Children’s book author, producer, and arts educator

❧

Indians are 1 to 2% of the United States. Most Americans live in cities or suburbs where they don't see Indians. In a handful of places in the U.S., you see Indians as actual political figures important in daily life...but most people never see Indians. People come into our museums and they think they've never seen an Indian before in their lives.

–PAUL CHAAT SMITH

Associate Curator

Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

I think the historical novel is plural and multiform and at the moment, in good creative shape. But the kind of historical novel I write – which features real people, rather than using historical events as a backdrop – is less favoured. It imposes a burden of research, which can be difficult at a certain point in a novelist’s career – because to do it properly takes time.

You can write that kind of fiction first – before you’re even published – or you can do it when you are established – but when you are in mid-career, your publishers don’t like it if you say, ‘My next book will take five years.’

I don’t see myself as confined within genre. The people I write about happen to be real and happen to be dead. That’s all. It’s interesting to think what expectations people bring to historical fiction. Particularly with the Tudors, it’s hard to avoid the expectation of romance, and of pre-digested narrative that conforms to the bits of history that people remember from school. And so some readers find it’s too challenging, and post abusive reviews. They don’t locate the deficiency in themselves, or like to have their prejudices disturbed. The form tends to conservatism. So you can find that you have, in fact, attracted the wrong reader. Correspondingly, if you manage to break down a prejudice against fiction set in the far past, that’s very positive.

I think it’s important not to confuse the role of the fiction writer with the role of the political journalist. You need distance to see the shape of events. So for me, near-contemporaries like Mrs Thatcher can only have a walk-on part.

–HILARY MANTEL

Novelist, short story writer and memoirist

❧

So, I started the program called Shelter Songs. I'm in two shelters now and expanding to 4 or 5 throughout the city. It's a nice thing to just look at them and say, "I'm with you for an hour. I'm here to serve you. Whatever you want. I have no agenda on what we're going to write. And it's incredible how generous everybody who walks into the sessions are because they show up. They don't know me. They just see a woman in a room with a guitar, and they show up and they've got some faith in it. And when they hear their words come back to them, they light up because they're like, "Oh, wait, that's like a real song. That sounds good.”

And they get excited by it. And then what I do is, I tell them, “Okay, so we finish with our session,” and then I go away, but I give them a download card and I say to them, in 48 hours your song is going to be on this website, and you can download it and you can share it.”

And all of sudden, “Oh, my gosh, I did this, and there's something tangible from it and I can share. And maybe I can reach out to some people I know and let them hear what I've been about.”

–TERRY RADIGAN

Musician and songwriter

❧

In the course of writing a novel I will sometimes lock myself away. During most of my previous novels there comes a point where I just go to the country and hide for 5 or 6 weeks. Sometimes it’s the first draft, sometimes it’s the second. There are periods when I feel like you just have to cut out the world and listen to the voice in your own head. [...] The first time I really remember getting excited about writing was when I was in 9th grade, when I was about 15 and I discovered the work of Dylan Thomas, the Welsh poet. That really got me interested in language and in fact for quite a while I wanted to be a poet rather than a fiction writer. It was only when I got to college, when I started reading Hemingway and James Joyce and people like that, then I changed my focus to fiction. [...] Story of My Life was entirely from a woman's point of view, although it was first person, not second person. But that’s the kind of book that I feel like writing now, something that’s very voice-driven, whether it’s first or second person. Something that is carried by the power of the voice. And that was certainly true of Bright Lights, Big City and that was true of Story of My Life. In some ways those books felt like they wrote themselves. I mean, obviously I worked hard, but I felt like I was often just carried along by the rhythm and the power of these voices that I had gotten hold of.

–JAY McINERNEY

Novelist

❧

Donc mon écriture est métaphorique par nature, je crois. L’angoisse, par exemple, est une expérience très banale qui peut altérer profondément la vision, l’ouïe, même l’odorat, l’équilibre corporel… Le personnage de My Phanton Husband voit les molécules du mur se dissoudre, par exemple. Ou la lampe pendre du plafond avec une modification de la verticalité. J’ai toujours, dans ma vie privée, aimé les scientifiques et ils m’ont apporté un énorme réservoir d’images. La physique quantique est très romanesque, par exemple. Ou le paradoxe de Fermi. Et j’ai lu beaucoup de science fiction dans mon adolescence.

My writing is metaphoric by nature, I think. Anxiety, for example, is a very mundane experience which can profoundly alter vision, hearing, even one’s sense of smell, one’s entire equilibrium...The character in My Phantom Husband sees the molecules of the wall dissolve, for example. Or the lamp hanging from the ceiling with an alteration of its verticality. I have always, in my private life, loved scientists, they have brought me a huge reservoir of images. Quantum physics is very novelistic, for example. Or the Fermi paradox. And I read a lot of science fiction in my adolescence.

–MARIE DARRIEUSSECQ

Novelist

❧

I've always done personal work, even though that's not necessarily what you're recognized for, that's the work that you're going to pass on. So my very first book was actually called When They Came to Take My Father, which was based on Holocaust stories and survivor stories. And I've always just loved documentary. It's really the heart of why I became a photographer. It just so happened in the world that I decided to work in, the other 50% is your commercial work, which you try to keep in the same theme of thread in terms of portraiture. It may vary in terms of the way that people receive it, but both things should be able to pass in the likeness.

–MARK SELIGER

Photographer

❧

That's really important to us. The diversity of thought and diversity of output and problem-solving approaches is important to us because you never know where that problem is going to get solved from. You never know where the good ideas can come from, and usually, it is not from one person's head. It's about conversations, it results from a conversation that is happening. You learn something from each other... And the more diversity you have in the room, diversity of thought and approaches, the more possibilities there are to develop something that nobody has seen before.

You know somebody in an audience a couple of months ago said, "Can I just ask you, how come every time I come to see Pilobolus it feels like I'm seeing family? And I think it has to do with that. Something feels familiar. You're looking at it and you go like, "Yeah, I get this!" but it also feels new.

–RENÉE JAWORSKI

Co-Artistic Director

Pilobolus Dance Company

❧

Characters begin as voices, then gain presence by being viewed in others’ eyes. Characters define one another in dramatic contexts. It is often very exciting, when characters meet—out of their encounters, unanticipated stories can spring…

Yes, my parents’ voices do emerge from time to time in my writing. My father was particularly funny, had a sharp wit & sense of humor, & I am often drawn to presenting such men in my fiction, an unusual blend of the sardonic & the tender.

–JOYCE CAROL OATES

Novelist, short story writer and memoirist

❧

I feel like anybody can make a church or a garden spiritual, but for me, the more interesting thing is to see if you can make holy or spiritual things that are just very ordinary. I also think that’s the truth. I think if God exists it’s everywhere, not just in a church, but in an ugly spot. In a spot where atrocities happen. There are all sorts of places that are holy, not just the ones that are defined that way by the culture. That’s always been a part of my work. From the very beginning.

–DARCEY STEINKE

Novelist

❧

When art forms become set, they become part of a certain dogma, whereas oral art is malleable and constantly changing. There is not the equivalent of a conservatory for this because there is nothing to be conserved, in a way. It's an organic or living thing the tradition. It's unknown where it comes, who created this, you don't really know. And therefore there is no author and no authority. It's just a matter of respect and also of rebellion. I think there is a balance for those two when you're doing anything related to tradition. And everything is related to tradition, it's just that sometimes we're not aware...Every single word that we say etymologically means something else. There is a metaphor to every single word that we say, we're just not aware. But if we were aware, then it would become very interesting. And that's the quest for me to be constantly more and more aware because it's so beautiful. It's a quest for beauty as well.

–NANO STERN

Musician and songwriter

❧

One of the things I love about The Frick and our exhibition program is that we've made the most of our limitations, which is that we're not a very big place. We don't have great resources. We don't have very big spaces to devote to temporary exhibition, so we've always made the most of those limitations by doing small exhibitions that are highly focused and I, personally over the years, I've worked on very big exhibitions, but I really love small focused exhibitions. And I believe that the public does too because they're very clear. You can come in, you can get the theme quickly, you can understand it, and so we tend to have exhibitions that are both highly focused and have a great level of quality.

So this Poulet Fellows program allows these young talented people to basically have their first opportunity to do an exhibition. So they come up with an idea, and we facilitate that, but they learn how to do an exhibition working with our chief curators, with established curators. They learn how to come up with an idea, how to flesh it out, what objects are necessary to make that theme be realized within an exhibition space what kinds of topics a catalog should address or not, how to lecture about it. They learn all the practical side as well as the intellectual side of developing an exhibition. And we've had some highly successful exhibitions by these younger graduate students that have received international acclaim, so for a younger student to have their first exhibition written about in The New York Times and European journals as well is an amazing experience. And they do shows that I'm very proud of.

–IAN WARDROPPER

Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Director

The Frick Collection

❧

In an age of poorly-crafted political fictions and propaganda aimed at creating divisions between different sections of humanity and increasing levels of global violence, art is vital as a countering force. Art provides access to the realities of others and common ground; art provides nuance and an understanding of shared humanity, art provides access to human history and repeating patterns of oppression and destruction. Entering into the world view, hopes, thoughts, and feelings of others through the intimacy of art prevents the establishment of sociopathic mind-sets within populations.

– A.L. KENNEDY

Author, academic, stand-up comedian

❧

The Humanities Impact Program is, I think, a very impactful, thoughtful program of support and collaboration with a range of organizations that again is about trying to build some of these classical ideas into the contemporary practice where historically they have been ignored. In the US, the value has always been ascribed on the very direct, the immediate, the practical.

We don't study history enough, and we don't think about abstraction. We don't think about the kind of philosophical questions that can actually then be applied into very direct and concrete moments of our existence.

–VALLEJO GANTNER

Artistic and Executive Director

Onassis Cultural Center, New York

❧

Of course, for writers, the music of a sentence is hugely important. And, you're right, I have felt more and more a kind of strange insensitivity to prose–even among people who review books and seem to do this for a living–that there's a kind of dead ear. That may be the result of, as you say, the increasing importance of visual images as opposed to text, although people are texting and tweeting and all these things, so we haven't lost symbols. I mean, language is going to stay with us, but maybe the motion of a prose sentence, you can certainly see it in 19th-century letters written by people who had very ordinary educations, ring with a higher sophistication than a lot of writing today. And that's rather interesting. That may be due to the fact that the whole culture turned on reading and writing in ways that it doesn't now.

–SIRI HUSTVEDT

Novelist and essayist

❧

It’s shocking how little young people know about the past. I sometimes tremble when I am confronted by this absolute ignorance and, even say Americans, not knowing anything about the American past which is a new country with only about 300 years to talk about. It’s surprising. Or meeting young people, and they say “old movies”. Old movies for a young person is something like Pulp Fiction. And that for them is old. And so they ignore the whole history of movies, which again, it’s a very short history, and it’s very easy to master a great deal of film history in a short period of time if you make an effort to look at the films. But people are not looking back. They’re looking forward. So we’ll see. We’ll see what happens.

–PAUL AUSTER

Writer and film director

❧

Everybody is interested in the Universe, so communicating about it is easy, no matter the background of the audience...These pictures of planets, comets, stars, galaxies, etc. trigger so much imagination that one gets the attention and interest immediately...the beauty of our Cosmos moves all. Asteroseismology is the study of starquakes. Just as geophysicists use earthquakes to study what is inside our own planet, we use starquakes to learn what is going on inside stars.

Why is this important? Because we want to know how stars and their planets get born, live their life, and die. This happens on billions of years so we cannot “wait” to see it happening. Starquakes allow us to age the stars and do the research on a human lifetime. We had and will have soon space missions dedicated to hunt for exoplanets and study starquakes, and so we made a major step ahead in our research field.

–CONNY AERTS

Director of the Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven

Chair in Asteroseismology, Radboud University Nijmegen

❧

I firmly believe that the arts should be a part of everybody's education. It's not just learning the history of art, but it's about opening up creativity as a means that can be useful to somebody throughout one's life. So, museums can't replace the school systems. I mean, we're not big enough. And a place like The Frick, of course, is a very great museum, but it's a small museum. So we can only accommodate a certain number of students. What we try to do is reach that small number of students but reach them really well and really deeply and to try to give them a meaningful experience, which I think typically happens over time, rather than one visit. So we really encourage, if possible, that students come back and that they begin to feel that this is their place.

–IAN WARDROPPER

Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Director

The Frick Collection

❧

What you say is very interesting. How do we make the readers of tomorrow? Because it’s true there are many children growing up who do not have the same relationship to books that we did. And so we have to reach them with social and educational initiatives like yours. We need libraries which are social spaces. One of my children, he was not so fond of books. He likes fashion. If it relates to fashion, he will find out everything about it. And so I believe if you reach them through their interests they will understand the importance of reading.

–IOANNIS TROHOPOULOS

Program Director UNESCO World Book Capital Athens 2018

Founding Managing Director Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center

Founder of the Future Library

Former Director of the Veria Central Public Library

❧