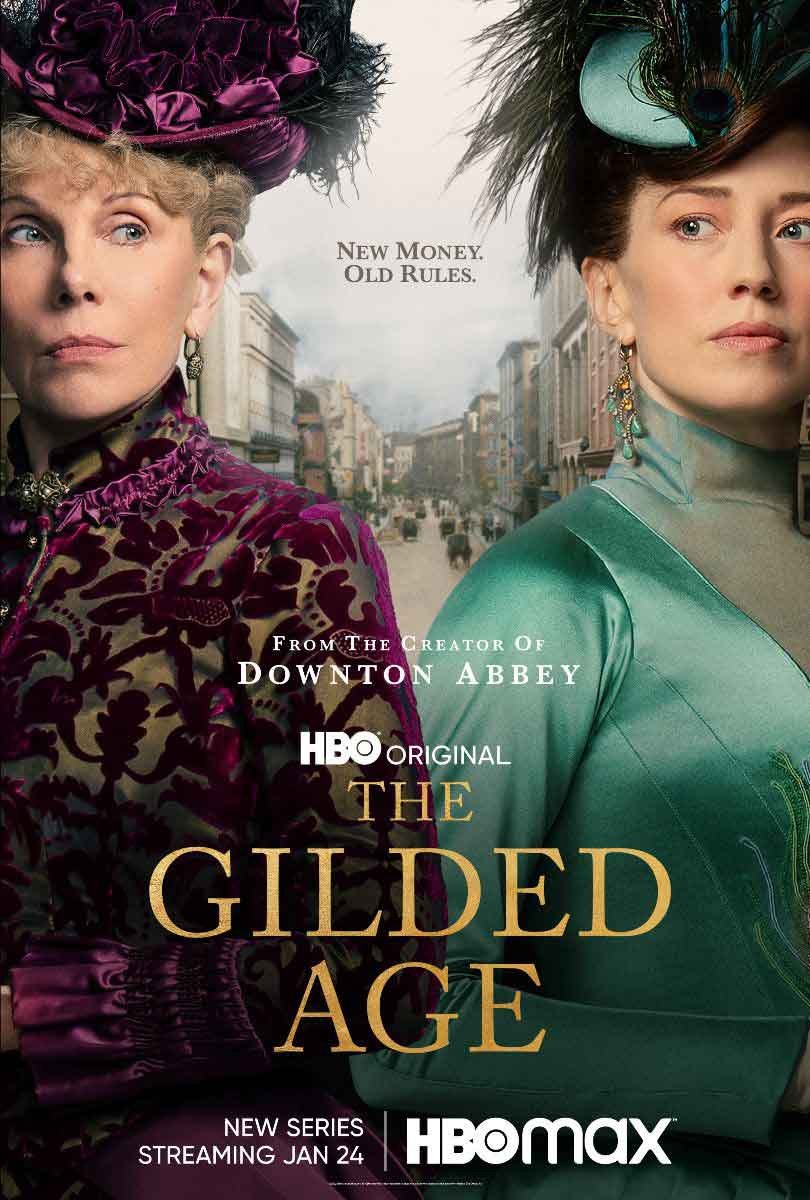

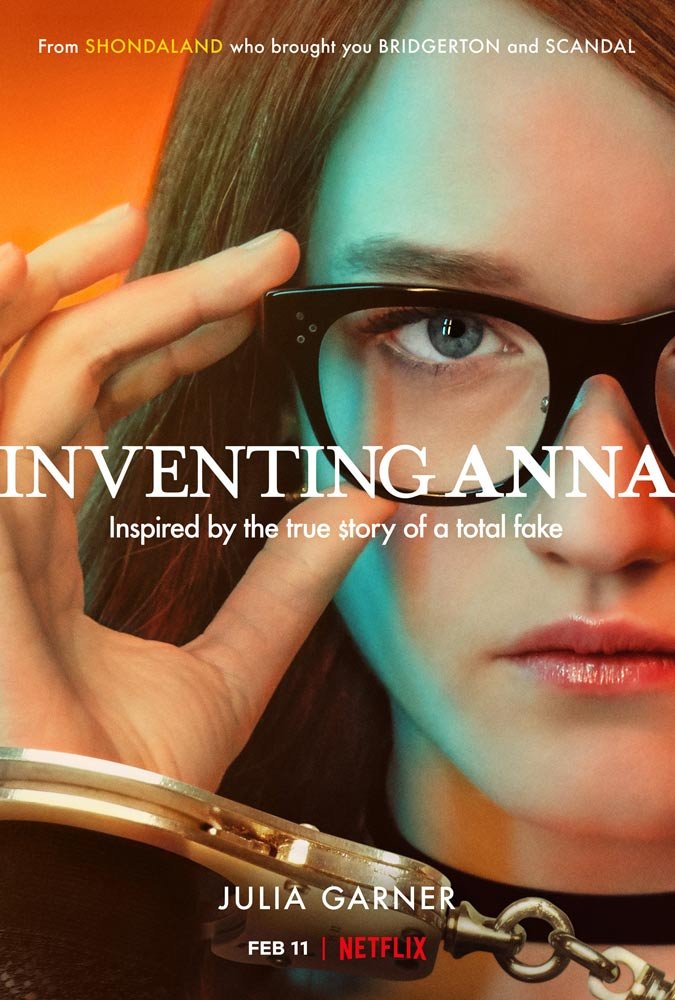

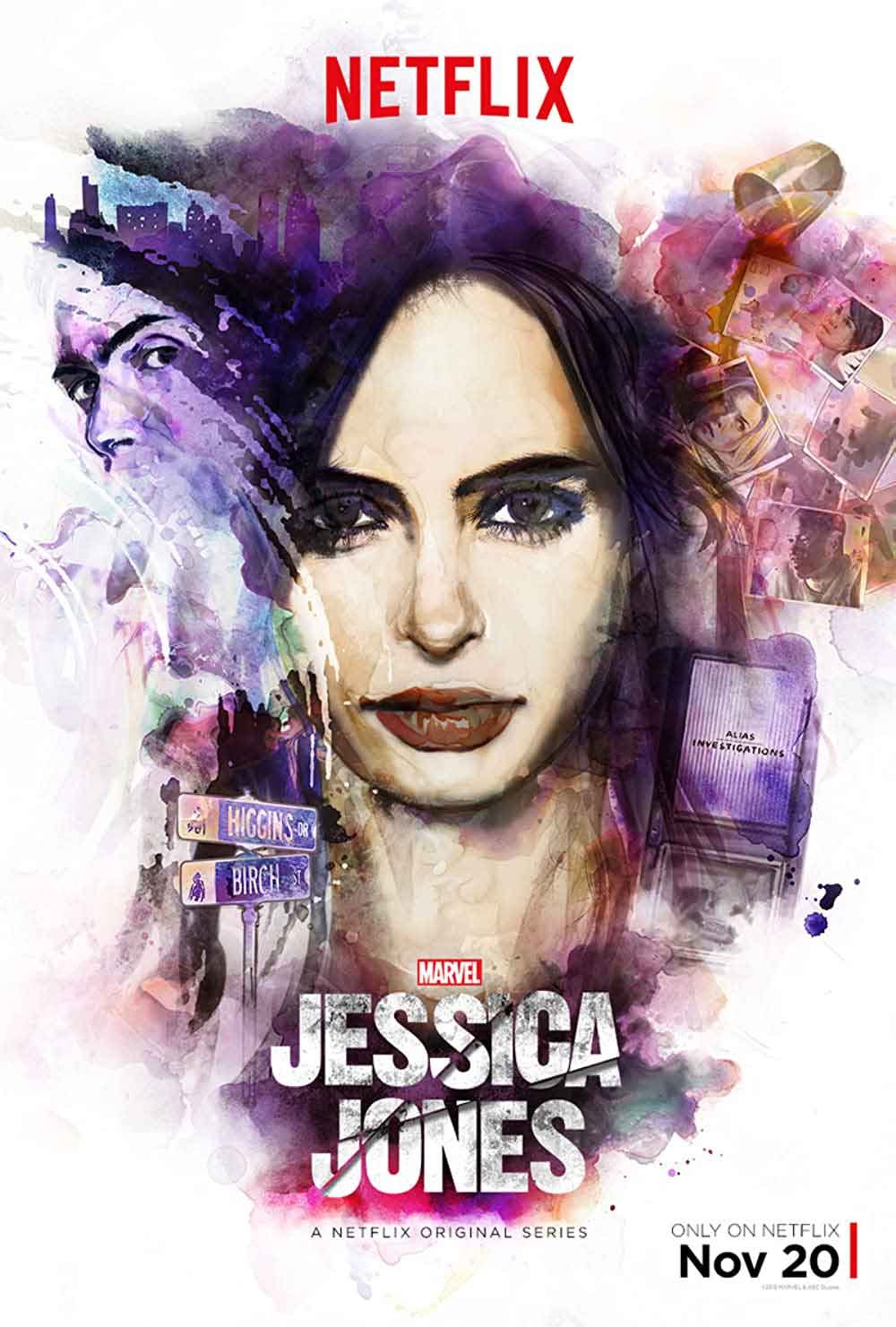

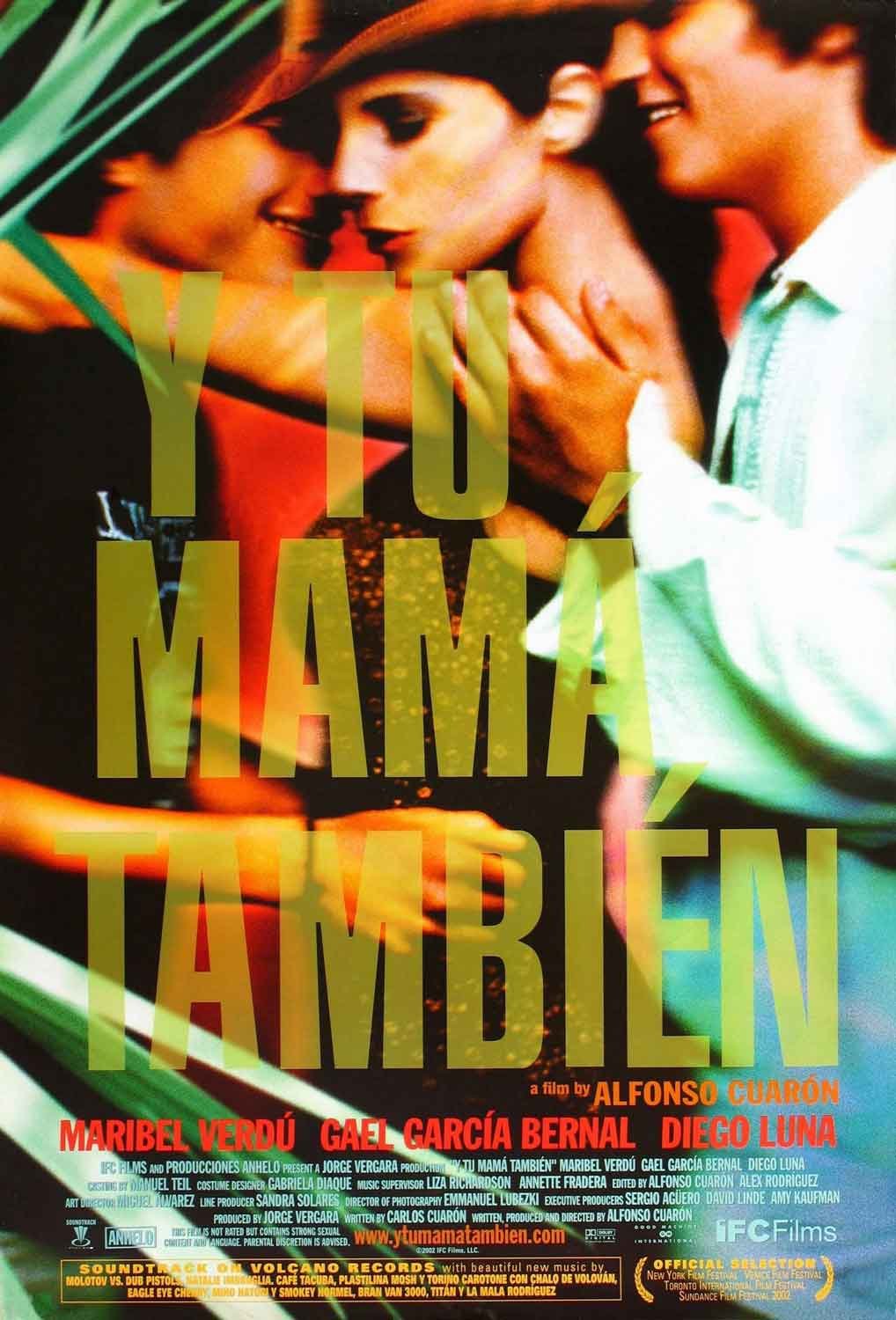

Cinematographer Manuel Billeter has worked across a variety of iconic and groundbreaking shows and films including Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, Iron Fist, Law & Order, Person of Interest, Orange Is The New Black, Lawless, and Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también. Most recently he has been Director of Photography on the HBO Max series The Gilded Age, starring Carrie Coon and Christine Baranski, and Netflix’s Inventing Anna, starring Julia Garner.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Who were some of the collaborators or teachers who were important to you, either those that you collaborated with directly or learned from or in history of cinema? Where you said to yourself, that's how you do that? I wish I could do that…

MANUEL BILLETER

What I think made me want to pursue film or what started my fascination with film and cinema were definitely Fellini, Antonioni, and Bertolucci; the masters, if you will, that kind of make you dream - make you just go to a movie theater, enter this space, and just have a communal experience. I know looking at the screen and just being completely immersed and experiencing stories or experiencing things that make you understand life more - or make you understand life less - and create a dialogue between you and the rest of the world.

After that, Alfonso Cuarón, obviously the collaboration was incredibly important and I learned a lot and I carry a lot of that in me, undeniably. Then, I also had the very good fortune of working as a camera assistant, and a camera operator with other cinematographers, so I learned a lot from them. And they became mentors in a way. And it was kind of like a fortunate path to becoming a cinematographer myself.

*

The camera is my tool of choice. It's what I've been given to express what needs to be expressed, what needs to be told. So I'm definitely very particular about composition or lens choices or camera placement.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So how involved were you in The Gilded Age to get the emotion in handling the camera or advising your camera operators?

BILLETER

I know both Vanja Cernjul and I really like working with our camera operator Oliver Cary who's got a brilliant way and a brilliant mind and he's always able to make suggestions, to make something better than I would have thought or I would have seen because sometimes I'm just busy just lighting something and that gives him time, and he always looks and finds a way to enhance what we set out to do the first place. So I quite heavily rely on his creativity and his artistry and his input to basically help me. Again, it's a matter of collaboration, the collaboration that goes between many departments and many different individuals.

And for what I had thought about how to use the camera to work in these two different worlds of the new rich and the old rich, something that Vanja proposed was to shoot the old New York with anamorphic lenses, which have a bit more of a nostalgic feel and are more associated with big, grand old Hollywood movies and the New York newly rich with spherical lenses, which are a little sharper, a little flatter, a little crisper.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

The lensing breathes beautifully. And I had thought maybe they brought you in as well because it depicts so many strong characters, strong female characters, and maybe they wanted to show a bit of a claws underneath this very civilized veneer, which is a motif of The Gilded Age.

BILLETER

Another aspect of why I was drawn to this specific project is because it's populated by so many strong female characters. And it looks like that's a common thread throughout the projects that I've done, there's always been a very strong female lead, an unusual female lead.

And, I must say, I'm drawn to that kind of storytelling, and I'm drawn to those stories because I think it's important to tell those stories and to inhabit these stories from a very female perspective.

So that's something that maybe I find myself almost in a comfort zone there, which goes against what I said earlier about needing to keep challenging yourself, which is true, but on the other hand, I think there are certain, motifs or certain stories that you're just naturally drawn to. The strong female character,

When I first read the script for the pilot episode, what really sprung out, what I really thought was an interesting way of discovering this world was that we discover it through the eyes of Marian (played by Louisa Jacobson), who's an outsider, who comes in. She's not in New York. She doesn't know much about New York at all, except that she has these aunts, two very wealthy members of high society. But this process of discovering this world through the eyes of an outsider and being dropped right into the middle of this conflict that the show builds upon, I thought was really interesting, and it goes into the motif of the strong female point of view.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I found it very interesting, the way that women dominated the scene within the home. Did you find it interesting to learn more about that?

BILLETER

That's how society worked then, or maybe it still works that way, there's a big influence, where women have a strong hand in a family setting. I think that probably the motherly perspective is something that's very dominant. At least at that point, it was the only real sphere of influence that was given to women because women were not necessarily in the workforce. It was very rare to have women in a leading role in any of the businesses or sciences or arts and letters. Back then, you had female writers having to publish under male pseudonyms because as women they wouldn't be published. Or as women, they wouldn't be recognized.

*

"By doing research and reading about the time and reading contemporary reports about New York and how New York grew very fast and how society was stratified, what was astonishing is that if I hadn't known that some reports were actually written in 1881 or 1882, if I didn't know that they were 140 years old, I would have thought they were talking about the current time. So it's something this incredible amassment of riches and wealth in the hands of a few people, it's something that maybe is always prevalent in any culture, but definitely, there were very strong parallels between the current time and The Gilded Age, where there was this very rapid ascent to immeasurable riches. It's just, Bezos, Musk, you name them, it's a similar kind of discrepancy between who has a lot and who doesn't. And so in that sense, it wasn't a stretch, trying to imagine how those individuals lived in the past because there are parallels to draw from in our current time.

*

Ozark, the way that show starts, it's all about money. Episode one, season one, it's all about money and how and our relationship, or Americans' relationship, with money and having enough, or not having enough. There's always this sort of worry about it and Julia Garner, she's just a wonderful person to work with because she just transforms so radically depending on what the show is. It's an honor to be able to witness such transformation and such dedication, and with ease.

But there's this smart marvel that I encounter every time I witness a performance like that, and she's just one example, but it's just the way actors can turn on and off a character, in between takes, for example. It's something that I find incredibly fascinating. How you can give all of yourself to a role and to a character and make it work and live it, or pretend live it. It's kind of a privilege to be privy to witnessing transformations like that. I have the highest respect for actors who embark on that journey and take risks while doing so. It's special.

*

After that, Alfonso Cuaron, obviously the collaboration was incredibly important and I learned a lot and I carry a lot of that in me, undeniably… And observing and learning while I was working, I could see, Okay, how does this person approach the scene? What is their lighting style? How do they relate with the crew, with production, and with actors? What kind of behavior is displayed? How do we interact with people? What is their process? I was being able to observe. That is invaluable. It was a good way to learn. My film school was being there, being in the front row, and keeping my eyes open, my ears open, and just observing, and learning by doing, by watching, and by seeing what should be imitated, and what shouldn't be imitated.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

There's that line by Christopher Isherwood. “I am a camera…”

BILLETER

I was maybe 19 or 20 years old when I read Goodbye to Berlin. I was in Berlin and that paragraph just really struck me. "I am a camera, with its shutter open, quite passive. Some day all of this will have to be developed, printed, fixed."

And I thought, I was dabbling in photography back then already, so the terminology and the photographic process was not new to me. It really resonated with me a lot because that sentiment allows you to give yourself time. That nothing has to be fixed and chiseled for eternity right this second.

*

What was I like as a young man? I forgot when I was a young man... I don't know. I know that as a kid I was very shy and maybe as a young man I started shedding that a little bit. What was I like as a young man? Maybe a little bit adventurous. Adventurous in the sense that, exploring more than just finding, trying to find a path in this life. And it's a process that took me probably quite a long time to get to where I am now.

So, maybe it was just a meandering, way of, observing and letting things percolate, and then, you having the. The privilege of manifesting them and making them concrete in the shape of moving images.

So that's something that really sprung out to me. And I remember when I was thinking about this interview here that quote came to my mind, and I looked it up again because I think that's a very significant way of what the creative process can be. That's also why I like it because of this, not timelessness, but at least this prolonged process of coming up with something manifest.

I really do like the prep work, the pre-production work on a project is probably the best because, it gives you time, it allows you to come up with ideas and to mull over them and to change them, shape them, to redirect them. And then when it's go time on set, that's also incredibly exhilarating to finalize it in that moment and say, Okay, this is it now. This is it. But there's also something very daunting about it because you know that after that, you can only tweak it at that point. After that, in post-production you can work on it, you can grade it, and can shape it a little bit more. But in essence, the moment where you're on set and you implement the plan that you came up with your collaborators, that's it. Then, there's no redo. So there's something very daunting about it, but there's also something incredibly exhilarating to be able to complete it.

*

I work in America. And I love being here. I love New York. It's always a source of a lot of inspiration, but I think what defines me most is maybe the way I was brought up bilingual Italian and German. I think it maybe also sparked some sort of a creative drive, knowing that there's more than just one way to express something.

Obviously, there are multiple ways to express something in the same language, but I had this advantage from birth, basically, to actually know that you can actually express the same thing in two different languages with two completely different sound systems and be able to switch back and forth and to see the differences in verbal expression as well. So that's something that probably defines me more than being part of any specific nationality.

*

And then there's another element that sadly isn't or only extremely rarely is available on set while we are making these images, which is the music and the rhythm. I always find that what I do, that cinematography, I find it very musical in a way. There's a certain rhythm in it, and there's a certain tonality in it. Just the way it has the same temporal continuum. I always feel that there's a strong parallel and synthesis between music and cinematography.

Most of the time it's a surprise when I see what kind of music or what kind of sounds are being added to a scene. And I always feel very flattered when I hear the music to it, just to see that as someone's creation actually added so much to the depth of the images that we created. I find that I'm generally grateful when I make this discovery. Sometimes we do know on a certain project, okay, this song is going to be playing or this theme. Or sometimes the director will say, Think such and such for this move. I'm going to put something in the vein of a specific artist or singer or musician. And so that gives me a guide of how to marry these two temporal elements, like a camera move that I know should match the music and vice versa.

But again, it comes back to the aspect of collaboration and of all these different aspects, all these different creations, kind of building each other up towards something bigger and grander and more powerful than you would have thought. Or that would be possible if you were just by yourself.

*

I still look back very fondly at Y tu mamá también because it was one of the very first projects I worked on. It was just an amazing privilege again, to be able to work with such incredible talent. I was able to see all of the cinematographer's work. And Emmanuel Lubezki was and is an artist that I highly respect. And so being able to sit in the front row after the fact, I wasn't on set. I was just in the editorial department, but I could look at the dailies. I could look at rushes. I could look at deleted scenes. And I could study the way it was shot. And then, later on, sit in during the coloring process when he was in town for a day, and he took time off another job to come in and work in color grading. And just being able to be in that room was incredible because to me it was something that I could, in a way, only dream of. And the film is great. It really spoke to me. Just the way it was told, the way it was basically speaking about so many different things, so many different aspects of society, so many universal truths, if you want, without really speaking about them. There's no exposition at all about it. It's just you have this narration of life, in a way, or these comments about life. And they open up so many depths of history, of culture, of the characters.

I found that incredibly important or incredibly fascinating to not necessarily spell everything out, but to leave enough room for interpretation for the audience. I don't think that the audience necessarily is better served by having everything explained and everything presented on a platter, just in tiny, small little bikes that are easily digestible.

I think it actually creates a much more immersive discourse. If you leave certain things unspoken but mention them and then leave the audience the freedom, the creative freedom to fill in the blanks or to construct a narrative that is maybe not necessarily explained or not necessarily the right one, it makes you an active person.

It makes you an active member of this dialogue. If you let them in, and I think one way to invite an audience into your stories is to leave room for interpretation and to let them witness something without necessarily explaining every single bit and, telling them how to read this or how to see this, but just giving them some sort of creative license as well. I think that's important to maintain that level of involvement from an audience because, in the end, we tell these stories for them as well. Or mostly, we're not telling them to ourselves. We want to go wider with it and touch upon something that resonates. There are many ways to approach it, but I find that maybe the open-ended approach may be more interesting rather than the approach that explains everything and leaves no room for any doubt.

Main photo credit: Sarah Shatz

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk and River Zhang with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this episode was River Zhang. Digital Media Coordinators are Jacob A. Preisler and Megan Hegenbarth.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).