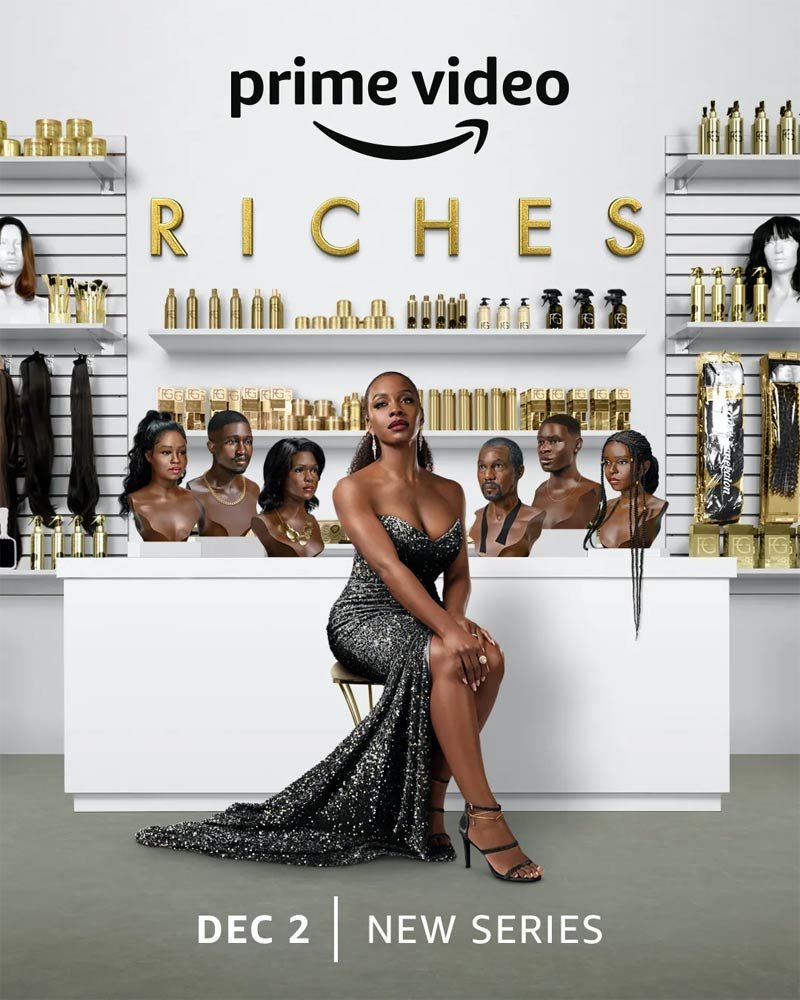

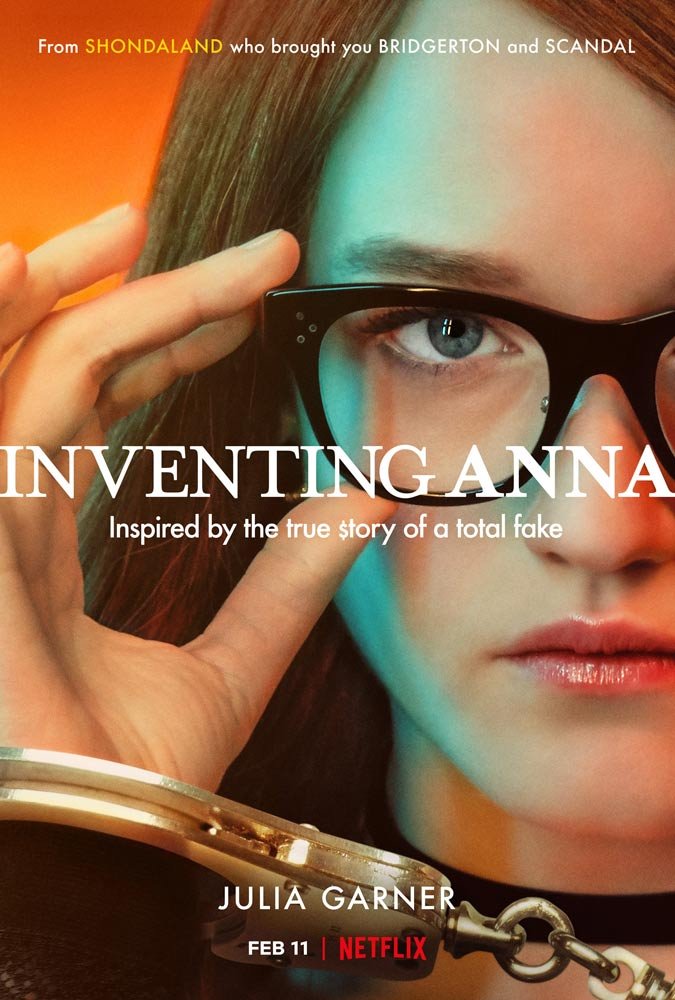

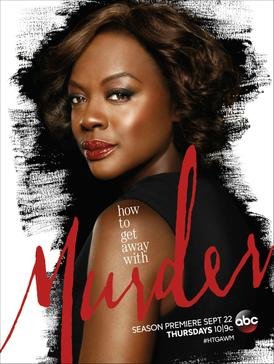

Abby Ajayi is a British Nigerian writer and director who serves as a show creator, executive producer, and writer on the Amazon Series Riches, which is currently on Amazon Prime and premiers on ITVX in the UK on December 22. She has previously worked on the shows Four Weddings and a Funeral, How to Get Away with Murder, Inventing Anna, The First Lady, and Eastenders. As a result, she had the opportunity to learn under the likes of Shonda Rhimes, Pete Nowalk, and Tracey Wigfield. Abby’s next project is the Onyx Collective on Hulu’s limited series The Plot with Mahershala Ali. She is adapting the eight-episode series from Jean Hanff Korelitz’s novel of the same name.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You worked on so many interesting shows. For your first project as showrunner and writer of Riches, why did you decide upon a family business drama set in the black beauty industry?

ABBY AJAYI

I think Riches has all the hallmarks of the things I've worked on before in terms of complex, slightly subversive women. At the heart of it, it is negotiating power dynamics. And at the heart of it, there are two very complex and yet vulnerable black women, but I've always loved family drama shows and particularly family businesses, whether it's fictional ones or in real life. I think whether you're talking about the Hiltons, the Kardashians, or the Royal Family, the dynamics of how, where power and money and blood merge is just such a potent and combustible mix that I've always been intrigued by them. I watched them growing up, whether it was Dallas or Dynasty or Six Feet Under, so it was a space which I was really interested in, and wanted to write a black family business show.

Myself and my producers, they knew my interest, and we talked around what would a black British business be, and they were interested in cosmetics, which I thought was a really good start because obviously, that's incredibly visual, but for me, hair was the piece that kind of tied it all together. A hair and cosmetics business because black hair is often so politicized, and it's such a way in which black people are sometimes policed in terms of having dreadlocks, having relaxed hair, whether they wear wigs. So it was a way in which we would have a glamorous visual for a show and an entertaining world that's aspirational, but still have a layer in which we get to tell substantive issues about black beauty, about black ownership, about how the spoils from a very lucrative industry often don't go back into the black community. So that's why I was interested in that. It could be glamorous and fun but also have slightly more in-depth issues to talk about as well.

So, in terms of going into the UK as a first-time showrunner, of course, the UK and the US systems are quite different. Really the showrunner model is very much the American system. While the UK historically has a much more lead writer who then hands over the scripts to the producer who then hands them over to the director.

But I was clear that I do feel that if one has the desire and the ability to be a much more big-picture showrunner, I think that's to the best. That benefits the show because there's a creative voice running all the way through. This isn't a movie, where it's a director's medium. It is the writer's medium, so I think the writer should be across producing and also empowering the director, but there is a clear vision.

*

In terms of leadership, it wasn't very much about ultimately starting to say, Okay, this is what it is, and being confident in that. And also acknowledging when one makes mistakes, you know, because you're making a lot of decisions in a very short period of time.

And I think it's important to give credit where it's due as well and that was also true of being a director. It's important to give credit. So have a vision, and work with those people to have the vision. Listen to what they're saying, listen to their ideas. And making television just makes it crucial to sort of have a vision, but be able to pivot.

*

Really early on, a producer said something to me, which I thought was just the worst thing ever, and she said something along the lines of you have to understand you aren't necessarily going to peak early. And at that point, that seemed like a horrible thing to say to a wannabe writer, but I think in retrospect, almost about 20 years into my professional career, it is a really good note and it's a note that's even more important now because, at that point, it was like I wanted to have my first show by this age.

You have these markers in your head, but writing careers are unpredictable. You know, there aren't sort of linear, you get promoted each year. It's just, the industry is changing. So I think it's important to be really aware when you start on the endeavor, it could be a longer journey than you imagine, and the fact that it's not happening right away isn't necessarily indicative of failure.

If you keep writing, if you're constantly learning with all the new scripts, and just keep doing the work... I think particularly a generation for whom experience feels like a weird thing because they grew up in a world where Zuckerberg was a billionaire at 20-something, so they expect to land on their big ideas so much earlier.

And so that creates a lot of anxiety and fear and a sense of failure so early on, when actually just living your life, keep writing, keep doing the work. It might take longer, you know? But this idea that you are obsolete by 30 if you are having a hit the thing, I think it's just really just a terrible trauma and burden to carry on one's self. So it might take a minute, but it can still happen. It can always happen.

*

I think leadership, particularly for women, can be a very dicey proposition because there's a lot of unconscious bias that we have to unpack, and sometimes that's internalized as well. And sometimes it's when you go before other people, but I think the confidence to know that one has earned one's place there. And it was important for me to remember, I do not have to be perfect because there is a perfectionism thing, you can and will make mistakes, and that shouldn't mean that you never get another opportunity or that you are punished for it.

And if your collaborators aren't human and empathetic enough to know that we all make mistakes, sometimes that's a problem with the collaborators as well. And leadership is also about picking the right people, you know? Sometimes if you pick the wrong people, moving on from that decision as quickly as possible to rectify it.

I feel like in a way learning to be a producer and to showrun... and the character Nina is learning to do those things as a CEO as well. First thing I think was that understanding that these things are incredibly collaborative. You know, you can be more than sum of your parts with the people if you have their trust and you listen to them. But I also think it's important to remember that the buck stops somewhere, and there has to be a decision-maker. So it's that thing about trying to be a better listener and listening to the people around you and empowering the people around you to do their jobs well, but also being able to have those sticky, difficult conversations.

*

I think for prose, the key appeal for me is being able to be in someone's interior life. You know, being able to dig into the ways in which one thinks, and the contradiction between what one is thinking in the moment and what one's doing, which you can do on screen as well, but there is a lag. There's a great opportunity to do that in the moment in fiction, but the other I think I love about fiction it is one can play with ideas and themes much more as opposed to - I feel like sometimes the process of making a film, the process of making a television show where there are so many steps in the development process whereby you have multiple people and it's best if in the collaboration where they're really helping you shape your vision, but sometimes it's more difficult when the desire for everything to be really clear for a television audience can have the effect of smoothing down the edges, smoothing down the complexity, smoothing down the contradictions so that it's a much more consumable TV piece.

I think there's just much less space for difficult or hard-to-categorize television work. But in fiction, I think you can have those works. It's not about smoothing out and taking out all the complexity or having everything be really clearly easy to consume. You can have much more complicated ideas and things playing with each other and dancing with the audience really.

And there's much more space, I think, for the audience to interpret. You can leave more space for the audience to interpret as opposed to when you've had to film it. You have to be very clearly defined with decisions. You have to define what color she's wearing, what bed she's sleeping on, what lampshade... So I like that there can be a slightly more amorphous, unfixed quality to fiction that I find interesting.

*

My siblings are not particularly like the characters in the show, I'll say that. There's actually quite a big age gap between me and my siblings. We span the full span, like 16 years. I think what it taught me most is about relationships, which is the meat of drama in terms of like, you're a unit in terms of the four of you, but you also all have different relationships with our parents. You also have different relationships with each other. So it's just that thing about the group dynamics amongst when you have multiple siblings is always interesting because you really learn about the different relationships, about the different ways in which parents treat, value, and love their kids - which isn't to say the love is unequal, but it's different. It's a different relationship. I think particularly writing a large ensemble like the Richards in Riches, it was important for me to show that just because you're all there doesn't mean you all feel the same way about certain things. And even just because you're all black doesn't even mean you feel the same way about certain things.

You know, that debate about colorism kind of reveals that you have different world views. I think having lots of siblings taught me a lot about relationship dynamics, group dynamics, the importance of support, and the ways in which we are kind of all rooted in our family. The first hurt to lodge there, but also the kind of the bedrock of confidence and how one moves in the world and self-esteem is tied up with siblings, I think.

*

I think that it's important to know that you can be learning the whole time. Your teachers can be not necessarily connected to you. We have more opportunities than ever before to see what people are doing. I'd caution against thinking you can only learn from people just like you because that's something I've seen a lot. I think it's incredible to be able to have black women who I've learned from, and who have been mentors for me, but equally, some of my best ideas have been learned from my white male peers. I think you can learn from anywhere and thinking expansively about where your learning can come from, and who you can be inspired by, I think it's super important.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk and Naomi Zidon with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this episode was Sam Myers. Digital Media Coordinators are Jacob A. Preisler and Megan Hegenbarth.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).