This profile of Dr. Walsh was written when he was teaching at Lehigh University. A dedicated humanitarian who believes in the healing power of literature, today he brings the same innovative teaching techniques to the inner city students at New Britain High School.

It's five minutes before the start of class, but he's already engaged in conversation with the students steadily trickling in on this damp afternoon. Vincent Walsh, who at first glance could pass for one of them in his faded yellow button-down and casual jeans, apologizes to the class for the "ferocious" debate last week about the contentious Race to the Top, attributing his recent remorse to a Tai Chi revelation at 2 in the morning. Then a student, citing an accounting test, asks him if he can turn in his assignment late. No problem, Walsh says. At this point, most have settled in and Walsh is ready to begin. Welcome to the Fam Jam.

As the name implies, the course thrives on intimacy and improvisation, but this isn't group therapy or a jazz class; this is one of the many sections of the required, and therefore often dreaded, freshman composition and literature course. For five years now, Walsh, an English doctoral student, has attempted to break the mold with what he calls "owning the writing process," an alternative approach to freshman composition pedagogy.

"You're writing for yourself," he affirmed. "Not for me."

The process is quite simple. Students write a 750-word paper every week, and every fourth week they're expected to write a 1,500-word research-based academic paper. They are free to choose the topic of each essay, which has to be nonfictional. Walsh then returns their essays in a timely manner, though without a grade. He marks the papers only for the technical stuff -- weak construction problems, dangling participles, misplaced modifiers, subject-verb agreement and so forth. Another key component is that students read their essays out loud to each other. Out of the 300 students he's taught at Lehigh, only one has ever refused to do so.

Walsh tailored the method of teaching to students' needs and wants because, as someone who once taught in inner-city schools, he understands how difficult it is to motivate students when they can't identify with what they're being taught. Typically, a professor assigns students a particular selection of books, which they are expected to write about later. There are many benefits to this traditional scenario, not just at Lehigh but also in most campuses. Students share the effort in trying to approach the same story in different ways, as Addison Bross, Professor Emeritus of English at Lehigh, points out.

But Walsh insists that the traditional method leads too often to what students commonly label "bullshit papers."

He described this pervasive phenomenon. "You look at a text that bores you, you look at a prompt that you don't want to write about, and you imagine what you think the teacher wants you to say. And you say that, and every once in a while you throw in a fancy word to make it look good," he says. "That's why it's bullshit."

A former student of his, Jen Ingalls, abhorred writing in high school because she felt she was constantly trying to write about topics she wasn't passionate about. Come freshman year in college, her outlook on writing changed. "With Walsh's class, I reveled in the freedom of being able to choose my writing topic," she said. Ingalls is now studying to be an English teacher.

Bross recognizes the power of this first step in Walsh's writing process, saying it gives students more ownership of their essays. According to Taylor Hess, another former student, autonomy, instead of authority, empowered him to meticulously craft his essays rather than just push through them when he was a freshman in the class, and despite his rigorous course load as part of Lehigh's IBE program, he said he looked forward to writing papers every week.

As an old adage goes, repetition is the mother of learning. Runners don't prepare for a marathon by training once a month; they train constantly and build on each workout. That same idea is at the heart of Walsh's argument for weekly assignments, instead of the usual four or five papers per semester required in other composition sections. Practice, he believes, makes perfect.

But even then, he's not looking for unblemished essays. The current dogma across the country in writing pedagogy, he says, is thou must not put thy hands on thy student's paper. Of course, Walsh, who led peaceful protests over the Kent State shootings in 1970, swims against the current in everything, even when it comes to correcting students' essays.

He uses the metaphor of the master plumber to justify his hands-on approach.

"I've been a plumber for 40 years and I'm really good at it. And you want to be a plumber, so you're my apprentice. I'm not going to stand in front of a chalkboard and lecture to you and tell you what plumbing is about; I'm going to take you on the job and assign you simple tasks at first. And every time you run into a problem, you’ll call me over and I'll say, oh this is how you do this," he explained. "It's on-the-job learning."

His method of correcting the students' essays doesn't just involve a red pen. He makes himself available to his students, day and night, by phone or email. It's no surprise for Mary Walsh, his youngest sibling, to learn of the way he nurtures his students' writing.

Once, when Mary was younger, she shared one of her poems with Vincent and his friend who was visiting from college. The friend immediately disparaged it. Though she admitted it's still painful for her to recall the experience, a silver lining quickly materialized. Walsh, her oldest brother, praised the small verse because, she said, he believed it to be a sincere attempt at expression. She never wrote another poem after that; however, those comforting words from her brother encouraged her to keep writing, which is now a crucial part of her job given that she's a senior, three-time Emmy Award winning producer at CBS.

This optimistic attitude, she said, inevitably translated into his becoming a teacher.

"For every student - and every person - there are always fumbles and false starts along the way," she says. "Vincent's constructive embrace of that difficult process goes all the way back to encouraging his little sister to put pen to paper."

The writing process doesn't end there. Since day one, Walsh's students are well aware that they are expected to read their essays aloud during class. Students not only will be asked to write later in life, but they will also need to be effective public speakers, he maintains. Bross adds that this reading aloud teaches students to write for an audience and helps them visualize their own work.

Nonetheless, whenever someone is uncomfortable reading, or simply can't because of a sore throat, Walsh will offer to read for them, as he did that damp afternoon.

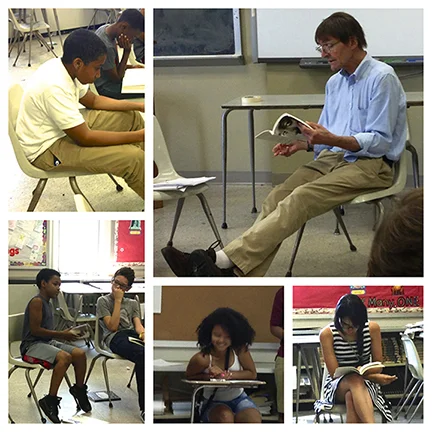

It's that time of the semester when Walsh asks students to write an evaluation of his class. He turns to look at Wes Corwin, a freshman, and with a simple gesture of his hands and an encouraging smile he seems to be saying, go for it. The student can barely reply; apparently, he has a sore throat. Walsh happily takes his essay and begins. Like a conductor guiding an orchestra, he feels each word, each sentence flowing out of his mouth, his hand gently rising and falling as if it were holding a baton. He keeps a steady tempo, pausing only to make a remark or to gauge the students' reactions. All eyes are on him, a feeling he grew accustomed to when his parents would have guests over and he would play Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata." According to Mary, Walsh was an exceptional pianist. For him, words are akin to musical notes.

"Writing is like music," he says. "Words have rhythm."

Walsh doesn't want his students' words trapped in their essays; he wants them to flow free and uninhibited and build into a symphony of discussion. This is where the magic of the Fam Jam happens.

What Danielle Daisudov enjoyed about the class was listening to other people recount their stories. "It's more of an evolving process as opposed to just reading a single tome of literature and then beating it to death," the sophomore says. "It's what English should be."

In a way, their two weekly class meetings are the chapters and the students are the characters developing a collective memoir. Walsh is not there to lecture to them; he's there to be what he likes to call the "expert facilitator." The desks are set up in a circle to promote a knights-of-the-round-table type of attitude; no one, not even Walsh, is above the students. The idea, Walsh says, is for peers to hear what each other is doing not only so can they be inspired, but inspire others, as well.

In addition, his students learn to defend their essays or their thoughts with evidence, whether the topic is climate change or concussions that football players suffer, by being put on the spot by fellow students. Sometimes many hands shoot up in the air simultaneously and the conversation rises to a crescendo, while at other times Walsh catches himself going off on a tangent before muttering to himself, "Shut up, Walsh." There's never a dull moment.

“It's no wonder that kids are pawing each other to get into his course,” says Vivien Steele, assistant to the English chair. Robbie Fagan, a graduating senior, who took the class in the spring of 2008, puts it simply: "The best class I've ever taken."

Perhaps even more surprising is the fact that Walsh has to do the same for his particular pedagogy. "He kind of has had to fight for it," said Steele, who finds the class an invaluable part of Lehigh students' education.

The feedback he gets from colleagues about his pedagogy is usually wary and skeptical because he deliberately breaks the rules of teaching and writing conventions. But Walsh garners support from the most unexpected people, such as Noam Chomsky. The esteemed linguist, philosopher and MIT professor has been in touch with Walsh for several years now.

"I've been intrigued and impressed by his innovative and creative teaching methods, and by the results. Students have clearly been encouraged to think for themselves, to take on and pursue challenging tasks, to explore and to create, and with real achievements, some of which I've seen," he said by email. "And the enthusiasm and gratitude of many of his students is unmistakable. That's quite a remarkable record, which deserves not only praise, but emulation."

Walsh's younger brother, Mike, explains that his brother was successful in everything as a boy, whether it was chess, music or baseball. But he wasn't selfish in his accomplishments. "He shared it with you, inspired and encouraged you to do it, too," he recalls.

What few people know about Walsh is that he had a terribly dysfunctional family background, a part of his past that to this day hasn't yet been resolved. Instead of acting out in destructive ways, though, Walsh combines his passion for writing with his desire for a close-knit extended family, ultimately creating the Fam Jam.

This article first appeared in The Brown and White, Lehigh University's student newspaper.

Liz Martinez is a video producer for the Huffington Post where she focuses on issues related to politics, social justice and identity/culture. She has covered the 2016 presidential election and President Obama’s historic trip to Cuba. Before she helped to launch the award-winning streaming network HuffPost Live, she was an assistant producer for Al Jazeera English's daily talk show "The Stream." She is a graduate of Lehigh University, where she majored in Journalism and French.