THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Tell us about your journey and path to founding Greg Kucera Gallery.

GREG KUCERA

I was born in 1956 in Bellingham, a small town in Washington state. I was raised in rural environments until 4th grade and from then on suburban areas of Western Washington. Graduated high school in 1974,in Federal Way, WA and attended University of Washington 1975-1980, graduating with a BA in studio art, printmaking. I was involved politically while in college and those experiences have informed my life too.

I sold shoes to put myself through college and then worked for Diane Gilson's gallery in Seattle starting in 1980. In 1983, I opened my own gallery and have represented emerging and well-known artists for 40 years now. I am semi-retired now, living in Albi, France but still working with the gallery every day.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Congratulations, this year marks the 30th anniversary of Greg Kucera Gallery. What drew you to the arts and founding the gallery? What is your curatorial vision?

KUCERA

My original intention was to go to school to become an art teacher because my own art teachers were the most important influences on my youth and in forming my life's path. In my high school years, I started going to Seattle galleries and fell in love with the business.

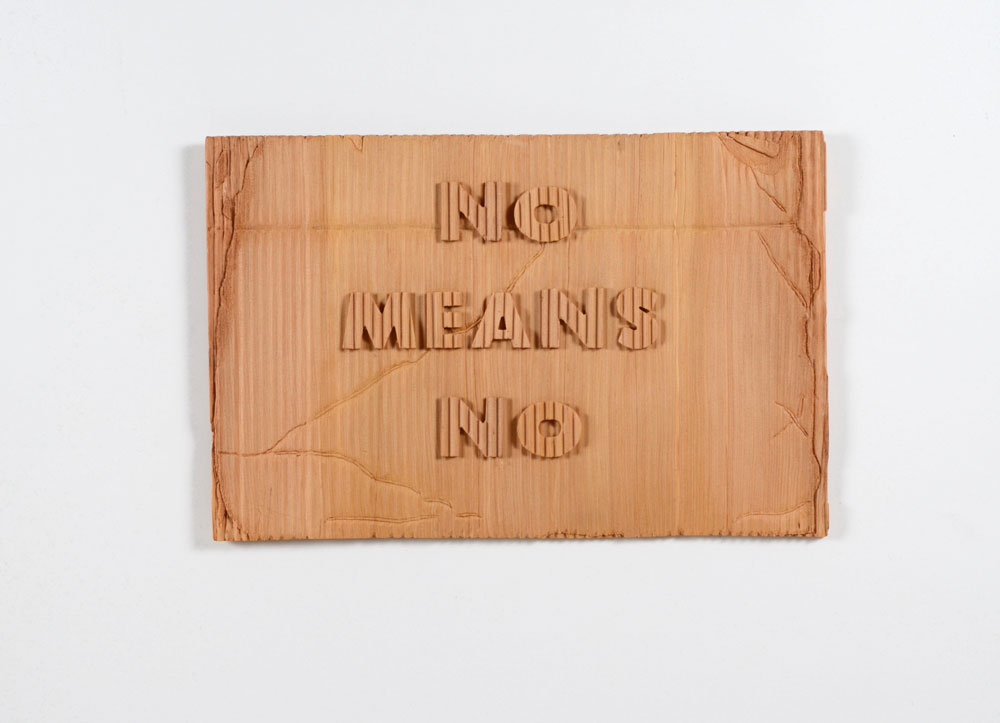

My curatorial vision lies somewhere between beauty and politics. The art I most admire gravitates between those poles and sometimes touches both. Beauty is harder to pin down because many works I admire may not seem lovely to others. I am drawn now to art that is increasingly formal and spare. Art that makes a powerful statement of contemporary commentary often has the power to move me.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You represent artists from the Pacific Northwest, as well as notable international artists. Tell us about some of your exhibitions and projects that are most representative of your work at Greg Kucera Gallery?

KUCERA

We represent a number of significant younger artists such as Humaira Abid, Juventino Aranda, Drie Chapek and Anthony White. These are artists we are showing at art fairs, and in impressive one-person shows, and for whom we have created markets. These young people expand the sense of the gallery as representing diverse talent.

The gallery began a series of politically themed exhibitions in 1989 with "Taboo," a look at the momentarily incendiary artworks by Andres Serrano, Robert Mapplethorpe, Sally Mann and others. This was followed over the next few years by thematic exhibitions such as "God & Country" and "This Is My Body" and "SEX" and "Bad Politics," all of which examined other aspects of contemporary political art. These exhibitions garnered the gallery attention in many different arenas and helped galleries in NY or elsewhere to see my gallery in a more national focus.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s we began to work with mid-career nationally known artists such as Deborah Butterfield, John Buck, Jennifer Bartlett, Robert Colescott, Mark Lere and Jane Hammond. Everything changed. We were showing a significant roster of well-known artists, emerging artists and local talent, examining the political motivations and cultural attitudes of our world.

We continued to open up the field of artists we would work with, taking on and doing significant early shows for Anne Appleby, Ann Hamilton, Kara Walker, Lesley Dill, and Kerry James Marshall. We also did shows in the late 1990s for Bill Traylor, and Morris Graves as a way of broadening the scope to include these earlier, venerable or deceased artists. Our 1994 exhibition of a complete set of Henri Matisse’s “Jazz” was a high point.

We became more and more interested in self-taught artists, working with James Castle, the Gee’s Bend Quilters and others such as Gregory Blackstock, who became one of our best selling artists.

In recent years, we worked co-operatively with other Seattle galleries to create some major two-gallery exhibitions for artists such as Michael Dailey and Michael Spafford, and others, who deserved some exposure they weren’t getting elsewhere at the museum level.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Now that you live in France, you are also considering extending the international vision of Greg Kucera to develop an artist residency program in rural France? Tell us about your vision for that and how artists can gain inspiration from the landscape and culture?

KUCERA

The residency idea is still in formation so I cannot say much about it yet. Most importantly, I want to reward several artists who have shown with the gallery for long periods of time and been a constant joy with whom to work.

As someone who never lived anywhere else but Seattle for my entire life, I realize that living in France for the last year and a half has been completely revelatory and rewarding. That change of scene can be a great inspiration to step outside of oneself. Perhaps I can offer an artist that chance to be somewhere outside of one’s quotidian life. Especially, working with artists I admire, then I know I will gain from exposure to their experiences as well.

But this is not likely to become a formal Artist in Residency program. Rather it will be limited to artists I know well because this is my personal home.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What do you feel is the importance of learning about the creative process and leading an examined life?

KUCERA

The creative process is a great mystery, never to be solved. I feel that artists are lights who shine the way for our culture by being creative in how they engage the existing culture and forever change it. I don’t expect artists to provide answers; I hope for them to provide the questions.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What qualities do you look for in an artist? What characteristics do you feel are important for those you represent and for artists creating work today?

KUCERA

In artists, I look for authenticity and for courage. I hope for a collaborative process of mutual respect. I don’t tell them what do to in their studios and, in return, I expect respect for how the gallery operates as well. Sometimes, we have artists who can’t quite accomplish respect for the gallery’s way of doing things. I find I have little patience for flakiness or insincerity these days. The world is rich with excellent artists and we are lucky to have maintained good working relationships some of which are still ongoing after 38 years or more. I grew up in this shared art world with some of these people and I would not trade the experiences I have had with them.

Three questions for me that have to be answered when I am looking at taking on new talent are, “Do I admire this artist? Do I admire their work? And what can I do for them?” Of the artists, I often ask, “What do you want the gallery to be able to do for you? Who are your peers?” Those questions often lead to revealing answers.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What are some ways that the artists you exhibit William Kentridge, Anthony White, Humaira Abid, Kiki Smith, John Sonsini engage with the important issues of our time?

KUCERA

Kentridge says it all with his statement that his work:

“I am interested in political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures, and uncertain endings. An art (and a politics) in which optimism is kept in check and nihilism at bay.” I remember reading that last sentence and feeling an automatic kinship with it.

The first time I saw his work, at the Venice Biennale, it mesmerized me, stopped me in my tracks, and made me watch the stop action video drawing over and over.

Abid’s work forces a fresh view by being a woman living within the Muslim religion and trying to find a voice to express her complicated relationship to the religion in a general way and to the forces within it in more specific ways. We don’t hear many voices from Muslim women because they are so often overshadowed by the male decision makers within the hierarchy of the religious structure.

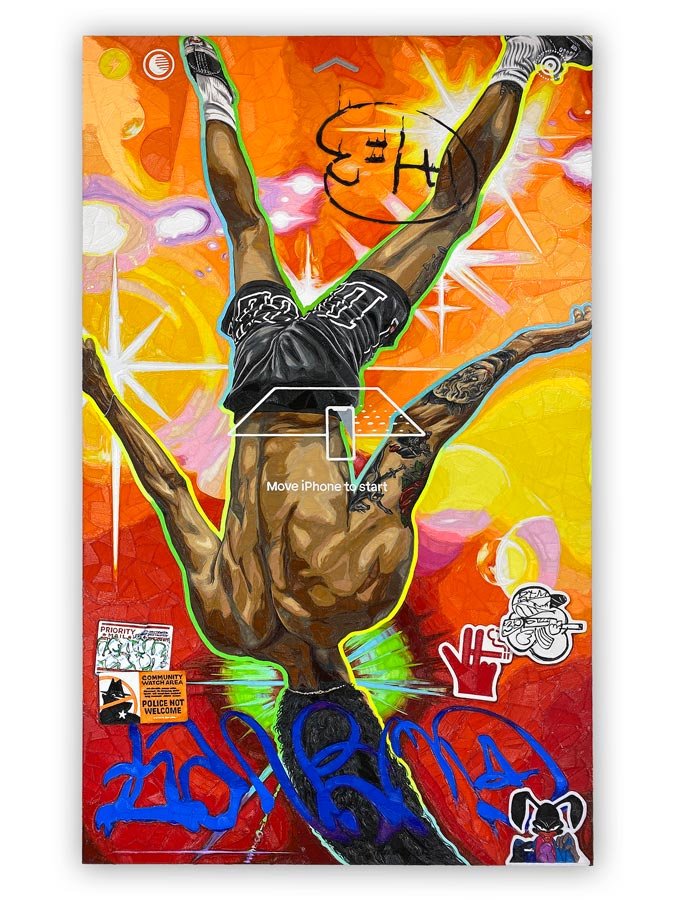

White’s work is so unsettling to me because he works within an arena of youth culture that is increasingly distant from my own. He is both a part of his generation, and a critic of it, in ways that I think I was critical of with my own generation. Our generations broke with the prior ones in profound ways and I think he struggles to bring a clear voice to a generation that is overloaded with stimuli. I marvel at the way people of his age bracket can be entranced by the glut of imagery in his work. I find a constant push and pull between attraction and rejection in his imagery.

The first time I saw John Sonsini’s work was in a review in Time or Newsweek magazine. I was reading it on an airplane, and it made me draw a breath and then hold it while I processed a feeling of, “Well, I have never seen exactly this before” while looking at a formal group portrait of Latino day workers. To this day, I have a great admiration for singularity of his vision.

Kiki Smith’s work often reveals a great contradiction between being attracted to its beauty and being repelled by the subject matter. She so successfully weds a gorgeous physicality to a grotesque subject matter.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What for you is the importance of the arts?

KUCERA

The arts are the filter through which any culture learns about itself. In any moment in time, the art that gets remembered and revered later is the art that unsettles us in our own moment.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What teachers and collaborators have been important to your journey as a gallerist?

KUCERA

My junior high school art teacher Jem Wear and my high school art teacher Lowell Schaeffer are by far the most important influences on my life. Both men encouraged me but also questioned me. Each taught me that my own artwork would not be the most important art in my life.

The artists I worked with changed my outlook so many times. I often feel like contemporary art is a moving target and to keep up with it is a great and worthwhile struggle. I also feel that I’m slipping behind in keeping up with it lately and I’m giving myself permission to do so. To disengage a bit, because the methods for showing art have changed so drastically in the space of my career.

My colleagues, Francine Seders and Sam Davidson, taught me more about the grace of art dealing than anyone else. Bill Goldston, on a more international level, was my mentor for many years and I learned a great deal from him about ethics and art.

Jena Scott, a longtime gallery employee, made me really see the value of the internet early on and she shaped our relationship to technology. We were the first gallery in Seattle to have a real website and it’s been invaluable from day one.

Jim Wilcox, and his spouse Carol Clifford, are my two business partners now. Their decency and moral standards make them great partners. I’m teaching them to engage a little blarney in the meantime. Having survived until my 37th year of the gallery without a business partner, I am thankful for them in continuing it for the sake of our artists and art community.

I can thank Larry Yocom, my lover, mate and closest friend for the last 40 years, for his constant trust and faith in what we’ve accomplished separately and jointly.