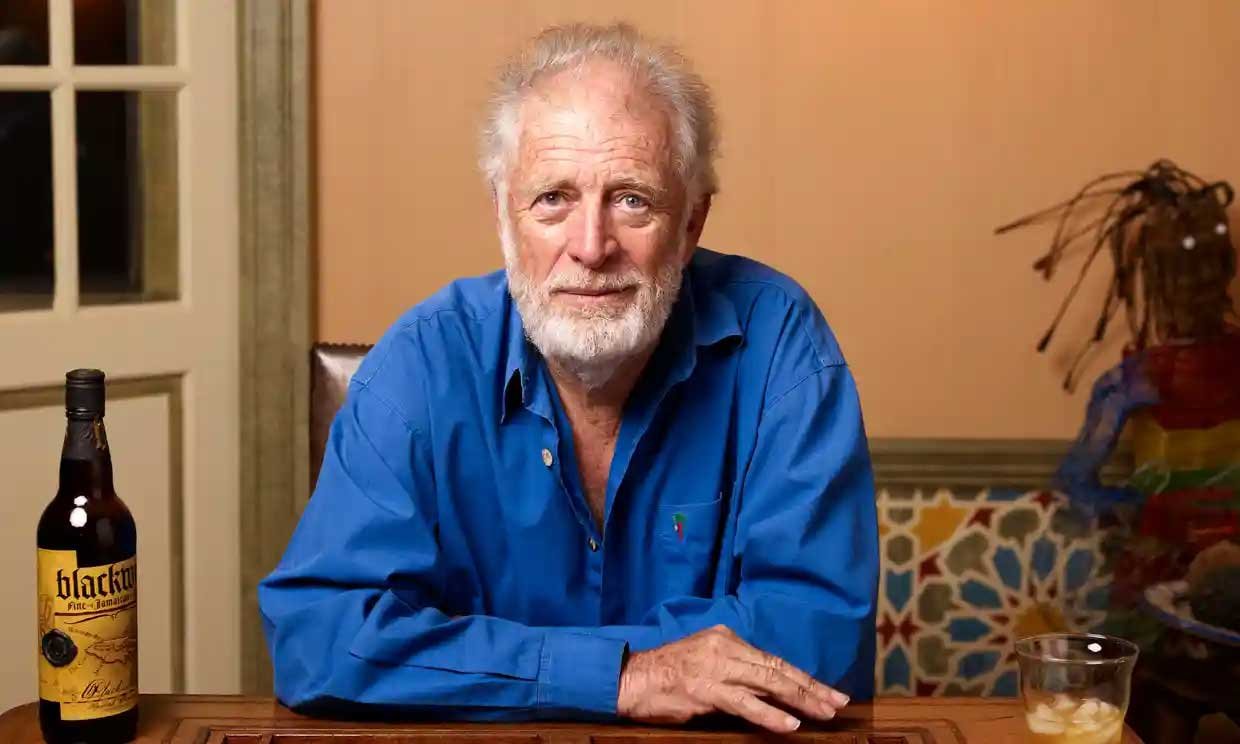

Chris Blackwell, an inductee of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, is widely considered responsible for turning the world on to reggae music. As the founder of Island Records, he helped forge the careers of Bob Marley, Cat Stevens, Grace Jones, U2, Roxy Music, among many other high-profile acts, and produced records including Marley’s Catch a Fire and Uprising. Blackwell currently runs Island Outpost, a group of elite resorts in Jamaica, which includes GoldenEye—the former home of author Ian Fleming. He received the Polar Music Prize “one of the key figures in the development of popular music for half a century”, and A&R Icon Award in recognition of his lasting influence on the music business. He is author, with Paul Morley, of The Islander: My Life in Music and Beyond.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You’ve got great instincts. How did you hone them?

CHRIS BLACKWELL

I think you need to be aware and see people be open to what can happen and get a feel, get an instinct. I think I've been blessed with instinct. I mean, I did not do well at school. I passed zero exams. I'm unemployable, but I've been blessed with having instincts. The instinct of U2 was seeing their determination, the fact that the music itself initially wasn't close to what most of my music was because most of my music was bass and drum. And most of their music was vocal, so it wasn't a certain kind of music that I like all the time. I like music from all different kinds of levels. And I think that's one of the things which was lucky that the fact that I heard all this classical music at deafening volume in the early days, so I sort of learned to listen and how to make your own little judgment that you end up liking most.

And I loved U2, and I knew that they would make it because there was a determination from them. And Bono himself was somebody who's just had a driving force, which just came out of him, you know? And as I said, this manager, I felt that he's going to be able to bring the band all the way. And I went back and I said to him, "I want to sign the band and I want you to follow the manager.” And that was really it.

I absolutely felt for Bob Marley to really make it worldwide as it were, he needed to change something a little bit. I didn't want him to change what he was doing, not his lyrics and everything else like that. It was more the instrumentation of it. I felt for Bob to be able to reach a wider audience that he needed to move away a little bit from that and focus more and more on his lyrics.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And I think that relaxed atmosphere that you had in Jamaica from a young age. People kind drifting in and out of your life and this ability to make quick friendships, but deep ones, it's something that you brought into your dealings in the music business, which was just really developing when you came into it. Looking at the artists you’ve worked with–Bob Marley, Cat Stevens, Grace Jones, Roxy Music, Steve Winwood, Amy Winehouse, and so many others. When I talk to people about you, they said there's “just something about Chris Blackwell.” It's like a mystery or something, but you tapped into something in them that allowed them to flourish. I mean, how did you do that?

BLACKWELL

I think from meeting them and getting a feel from them, and just what their personality, what their character was, what the energy that was coming from them, that I would feel. Do you know what I mean? I think that was really it. For example, I was not initially interested in signing Cat Stevens, but that was mainly only because I'd seen him before on television. And the song he was singing was "I'm Gonna Get Me A Gun." And I thought I don't get that, so when somebody said that he was interested to meet with me, I wasn't really interested because I felt already that he was going in a different direction which didn't sort of make sense to me, but when I finally met him and we just sort of sat down and he played a song. And then he played another song, and then when he played the song "Father and Son," then suddenly the lyrics of the song and what it meant and everything, I suddenly felt this guy is fantastic. You know, the I person I'd seen on television had nothing to do with this person sitting in front of me. And so that's really when I said to him, I opened up to him and I said, "Honestly, I wasn't really interested to meet, but this song that you've just sung for me is such an incredible song." And then we started to talk, and he started to open up and say, "Well, he had a difficult time with the label that he was working with before because they weren't giving him much support to do what he wanted to do. And so that was music to my ears because I felt that I could definitely connect with him. "Where Do the Children Play", that was the one that, just the fact that he was somebody who was thinking like that.

You know, in Rock 'n' Roll, it's a lot of rough and tumble. Whereas, when he sang that song, the fact that's what he had created and that's the direction he was going. I thought, well, that's really something. And that's why I immediately sort of just jumped on it and then said, “Listen I'd love to do something with you.”

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So, you're in London in the 60s, driving around in your Mini Cooper distributing albums. It's a little bit like guerrilla music producing. Very grassroots. Tell us what London was like back then.

BLACKWELL

Well, London was happening. Very much happening in the film business in England. Great movies were being made out of England and also The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, all that really started to explode. And what was really great, the music that they were loving was the music which was coming from the black music from America, the blues, New Orleans, of course, St. Louis, those different parts that music was coming to England, and that was what was really happening. Jamaican music was creeping up, basically through the Jamaican communities who lived around London and Birmingham and Bristol, etc.

There was one time when Mick Jagger asked me to come and meet with him because I think he'd heard the records that were coming up from me, mainly Jamaican records and things, and that's why he wanted me to come and meet with him. He was leaving Decca, and wanted to go to another level. And I said, ‘It makes absolutely no sense for you to come to my label because you already are huge.’

Well, Led Zeppelin…I was in a recording in England and going to be doing a record with a group called Traffic, which was led by Steve Winwood. And in those days, it took some time tuning your guitar up, different instruments and everything. Nowadays, all that's done in a second, but in those days, there would be a lot of time spent. And I couldn't contribute to that. And it used to drive me nuts waiting until it got all ready to start the songs. So I drifted into another room in the studio. And I went in, and I heard a record coming out, and I thought I've never heard anything like this before in my life. It was just unbelievable. And I said, "Who are these kids?" They said it's a new band, really. I said, "Well, what do they call it?" They said, “I don't know what their name is. Something Zeppelin or something like that.” So I said, "Well, who's their manager?" And it turned out that the manager was somebody who was a sort of, not a great pal, but a pal because we shared an office. He was on the fifth floor, and I was on the second floor in an office. And I went to see him, and I said, "Listen, I heard your band. It was just unbelievable." So, we kind of agreed on a deal that I would sign them for England and Europe. And the manager wanted to sign with Atlantic Records in America. So I said, "Okay, I'll have England, Europe, and you have America, Canada, etc." And then we shook hands and that was it. And, of course, it never really turned out because when they went to America to make the deal with America, Atlantic said, "No, we want them for the world." And so he came back to me and said, "Oh, we didn't really want to be with Atlantic," and I made a deal with them. And I said, "Nevermind." And I didn't mind because it wasn't something that I would have been able to help a lot with. I certainly loved what I heard in terms of that music, but I didn't feel that it was something that I could be involved in managing them or doing their recordings.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So for these artistic collaborations, I believe it also takes a lot to get you to say yes. I believe Grace Jones was on your radar for a while? How did that come about?

BLACKWELL

Well, Grace Jones was also one of those things where I was having lunch with a couple of friends. And this guy said to me, "By the way, there's this model who is just stunning, and I think she's wanting to be a singer. You should find out about it." So I listened and then a couple of days afterward she was in a magazine. And, you know, she's a stunning-looking lady. She's amazing, and when I saw her in the magazine, I thought, "Well, I'm definitely going to follow up.” So I tracked her down. And what happened is that she had started doing a recording because she was more in the fashion business. She was a model. So she was doing a recording with these two people who were in the fashion business and just outside of New York. And, she'd been doing something with them. And so I tracked them down, and it turned out that they were desperate to see if they could get their money back from the money they'd put into her doing a record. They did not want to be in the record business. It had just happened like that. So I met with them, and I remember this very clearly. They came to my office, and they were very nervous, and they were really hoping that I'd be able to make a deal with them because the record they thought was going to be costing about 10 to $15,000, but it was closer to about $60,000. So they were in a state. So when I went and sat with them, and I said, “Well, can you play me a bit of the record that working on?” And they put the record on ,and it was a song, called La Vie en Rose, but recorded by a kind of drum machine. And so they put on the record. Grace wasn't there or anything. It was just this couple in the clothing business. They put on the record, and there was a drum machine. There was no vocal. There were no instruments, nothing. And the drum machine played for about two and a half to three minutes before I heard a voice. And by the time I was at two and a half to three minutes, I thought, Oh my gosh, this is a disaster. This is going to end in tears. And then suddenly I heard the voice, and the voice sounded great. And I said to them, "Okay, I'll buy the record off you.” And that's how it started from literally as simple as that.

I hadn't met Grace. I just heard her voice when the record started. And that was it. And then she met the guy who had been producing that record, which was called Portfolio. That was her first album. And it did quite well. Not very well, but quite well. And then the second record didn't do so well. The third record also didn't do so well. And when I say didn't do so well, I'm not sure we would even release them, but then that was a time when I thought I would love to work with her personally in the studio. And I had a studio in Nassau, the Bahamas. And so I put together a band to come and play for her. Four people from Jamaica, one person from France, one from England, and all of whom didn't know each other. The four from Jamaica knew each other, but they didn't know each other. They didn't know what was happening. Grace didn't really know what was happening. I'm not the best-organized person in the world, so nobody really had been told exactly what was happening. So right at the beginning, it felt like it could have been a disaster. But in fact, it turned around completely and was wonderful. And we had three or four albums by Grace Jones. And that was it.

*

Tom Waits is amazing. Absolutely incredible. A brilliant, brilliant, brilliant guy. I went and stayed with him a couple of days in his home in California, and I slept in one of the rooms. And I found out about him a little bit from that because he had all kinds of newspapers in this room, and I was thinking, “Oh boy, he gets these ideas from these different papers.” And he was somebody who - he's a brilliant guy - somebody who just knows the world really well. And a very well-read person. And very, very smart. An incredible sense of humor.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Your mother was the original Bond girl before the films were made. She was a model for Ian Fleming’s great characters. You say it was an uneventful life, but to us who didn’t grow up that way, it seems like a kind of a magical childhood. The kind of childhood that's very hard for young people to have that kind of experience now.

BLACKWELL

Because I was not going to school and everything, I can remember clearly when Errol Flynn first came into the house because my father had gone down to the port to meet him. And he brought him up, and I remember very well him arriving. And he was such an amazing-looking guy, and he was a charmer, and we became friends. He was very nice. He took me down to his yacht which was in the harbor, and he allowed me to go and be wherever I wanted to be on the boat. In fact, he even allow me, because he was somebody who did whatever he wanted to do rather than what he was supposed to do, and he let me go where I wanted to be, which was under the bow of a sailboat. It has a net underneath it and that area there you are absolutely not supposed to go to for obvious reasons because if you drop, the boat runs right over you, but I used to ask him, "Well, can I just go down there?" Because I felt it was safe. And so he let me do that, and we'd come back to the house and spend some time and have lunch or dinner and there was a lot of laughter. And he was an amazing character, and he was so handsome. And I didn't know at that time what movie stars were all about. I didn't really know because, again, there weren't many films happening in Jamaica when I was 7, 8... So it was just really meeting this guy who was amazing, and he and my dad were friends very quickly. And then my mom, too. So that's really the time I spent with him. But he was very mischievous.

It wasn't about money. It was just a really different life, I guess, in a way. It was a really great opportunity because one would meet different people, and they'd be there for a bit, and they'd be gone, and then you may see them in a year or something later when they came back to Jamaica or something like that, but it was never something which was sort of organized. Different things would just sort of happen out of the blue, and they would happen also out of the fact that I spent a lot of time hanging out with the staff, and it was an extraordinary, thinking back about it, it was an extraordinary life. It was very, very, very different. And I guess it was just different opportunities of seeing different things happening in different ways all the time.

*

Miles Davis was the best teacher, always amused when I asked him questions. I was pretty cocky at the time, and I once asked him why he played so many bad notes, unlike Bix Beiderbecke and Louis Armstrong, who always played clean. He didn’t blink. He didn’t bite my head off. “Because I try and play what I hear in my head,” he said, “not what I know I can already play.” That, to me, was the essence of jazz, trying to get somewhere new and not worrying if you made mistakes as long as you got there in the end. On a tightrope, and wobbling a little, but eventually gliding across that tightrope.

*

Well, it's really great if you can be involved in doing something which brings something to people and lifts things. You know, if you can find a way to…when I say find a way, you just get an instinct of something, Oh, this is going to be fun. That can be great. I'm always looking…I don't know that I'm deliberately looking at things. I think things have happened, and I've seen something or got a feel for something or feel for the person or… I think I've been given a lot of luck.