Born in Antananarivo, Madagascar, Johary Ravaloson studied law in Paris and Réunion (PhD, 2002) before returning to his hometown in 2008. He worked as a lawyer, writing his novels and short stories in his spare time. Since 2017, he has lived in Caen, France and dedicates his time to the writing, translation and publishing.

His work focuses on Malagasy people as they are confronted with and accosted by the modern world, which brings changes that shake and sometimes shock them. His universe weaves together tradition and legend yet burns with a contemporary fire. Most of his characters feel out of place but try to cope. They are often romantic to a fault, inviting us to share in their belief that love leads to redemption.

He has been shortlisted for and won numerous prizes for his novels and short stories, including the Grand Prix de l’Océan Indien and the Prix roman de la Réunion des livres.

In 2006, he founded Dodo Vole Publishing with his wife, contemporary artist Sophie Bazin, starting a new trend of in-country publishing in Madagascar and neighboring countries.

In 2018, he launched the annual magazine Lettres de Lémurie which brings together 24 voices from the Indian Ocean region in each issue.

JOHARY RAVALOSON

At this time, I lived in Réunion, not so far from Madagascar, and whenever the media brought news of my country, it was about poverty, natural disasters, abandoned children, political aberrations, corruption, etc.

I wanted to talk about my country without talking about misery. I was looking for some hope.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

The novel is fascinating, drawn from a character from myth overlaid with contemporary concerns. Tell us about the character Ietsey and the origins and responsibility of his name?

RAVALOSON

I remembered the fabulous stories and myths of my childhood, especially that of Ietsy, the first man who, to have company, carved humans. Ietsy interested me because he was a creator, an artist.

Like him, I would make characters of my contemporary novel: create men in my image and women in the image of my dreams. I used the myth, continued it and built my novel between tales and the life of Ietsy Razak ; tales that explain if not illuminate the behavior of characters.

I did not have a story to tell at first.

I love Paris, Texas, the Wim Wenders film. While I was originally writing Return to the Enchanted Island, the soundtrack by Ry Cooder was stuck in my head, especially the “I knew these people...” voice-over where Travis, the main character, finds his wife, the sublime Nastassja Kinski, in a peep-show club, and starts telling her their story over the phone, without her knowing it’s him.

I loved Travis’ tone, and I wanted to use that tone in my novel. Eventually, I realized that what he told was also part of what I wanted to write: telling a story to the people who had lived it. A kind of search for what we have in common.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And in your search, you have a very improvisational approach to writing, as you shared when we talked in the Trinity Church in Paris. It reminds me of how jazz musicians speak about their process.

RAVALOSON

I did not know it consciously at the time but it was my way of writing, my sense of writing itself: to tell me a story that I’d lived through, which I discover by writing.

Of course, using the myth of Ietsy in search of other humans inevitably leads to a search for identity, history, and relationships with others.

This novel was inspired, as I said, by will for reparations. The main character is a walking island, like all people are to me. The hope is that he is aware of the world around him. Opening up to others and the world can hurt, but it can also enrich life.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Another part of your writing life involves a very different kind of writing. When you first came to France, you did not come here to be a writer.

RAVALOSON

I studied law at the University of Panthéon-Assas, Paris II, before finishing my Ph.D. at the University of La Réunion. It was a kind of debt to my father. I have always thought of writing and being able to give up law as soon as possible. However, until 2016, I worked in a consulting firm between two books and continued teaching at the university.

Henceforth, the development of our publishing house Dodo Vole that was founded in 2006 requires a greater investment. I keep the same time to write and in the meantime, I read, correct, translate and promote our books wherever possible (generally in book fairs and literary institutions in France and the Indian Ocean Islands).

Of course, before I came to Paris for studies, I was not unaware of the differences between the two countries (people, languages, histories, mentalities, cultures, etc.). These had become important when I realised that I was writing in a language other than my mother tongue and that I express myself for all francophone readers who do not necessarily know my country.

I came to writing by reading. I love reading. I always liked to read. There were not many books in Malagasy, especially for children. I read a lot in French. The first time I settled in front of my father's machine to write, I wrote...in French.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

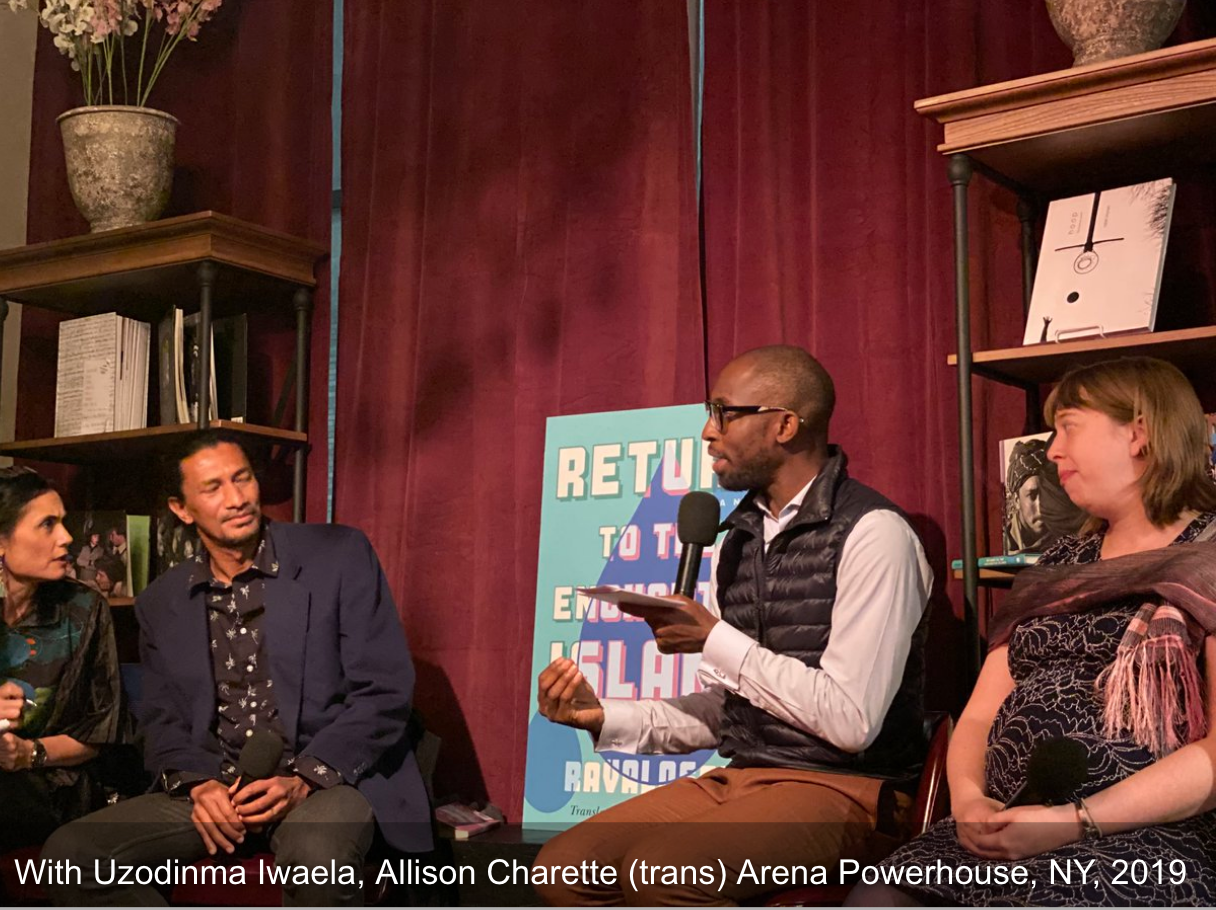

Through your writing, publishing, and translations, you are bridging cultures and generations.

RAVALOSON

As I continue to write in French, and my books often speak about Madagascar, it has become natural for me to translate. That’s why I consider myself as a bridge between Madagascar and elsewhere.

By the way, I found a kind of style in this translation and I want to look Malagasy in my French.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

How did your publishing house Dodo Vole (Flying Dodo) come about?

RAVALOSON

Dodo Vole was founded in 2006, for children. More exactly, we wanted to make children's art books. With a band of artists, we used to make catalogs for exhibitions in Réunion. While the disputed catalogs at the openings are often stored in piles, we discovered with our children that their books dragged throughout the house, on tables, beds, on the floor, always open. The first collection was born like this, and we wanted to show from the start artworks from all over the region, even if Réunion and Madagascar take up a lot of space: 30 albums all cardboard.

At the end of 2008, we moved to Antananarivo, and we created the Dodo Bonimenteur collection whose aim is to give children forgotten stories; 30 traditional bilingual (Malagasy-French) tales, illustrated by twin classes in Madagascar and France.

Then in 2010, as my first novel Géotropiques published by the Vents d'Ailleurs publishing house in France did not arrive in Madagascar or Réunion, I asked for a territorial publication right. The collection Plumitif, featuring stories about Madagascar or Malagasy writers, has now published seven authors.

In 2017, a new collection, DuODuO, that brings together an author and an artist. So far, we've published 3 bilingual books. Lettres de Lémurie continues these same efforts to make known the arts and literatures of this region.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

There is a very strong educational element to what you do, especially in your work for children. You are teaching through stories, you are sharing pride in your region, in its history and contemporary contributions to world culture. As you think about the future and the kind of world we are leaving our children, what do you think is the importance of storytelling, the humanities, and education?

RAVALOSON

My books tell the story of Madagascar, its legends and mysteries, the insular island, its nature and the history of contact with the other, with other people. I wanted to show that Madagascar is inhabited. Westerners discover Madagascar in history books (through Marco Polo, then Diogo Dias in 1500). I wanted readers to discover the humans who live there, with their contradictions and complexities. I just wish to write in the stories of the world, my part of bricks. I am part of the world, too.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process.