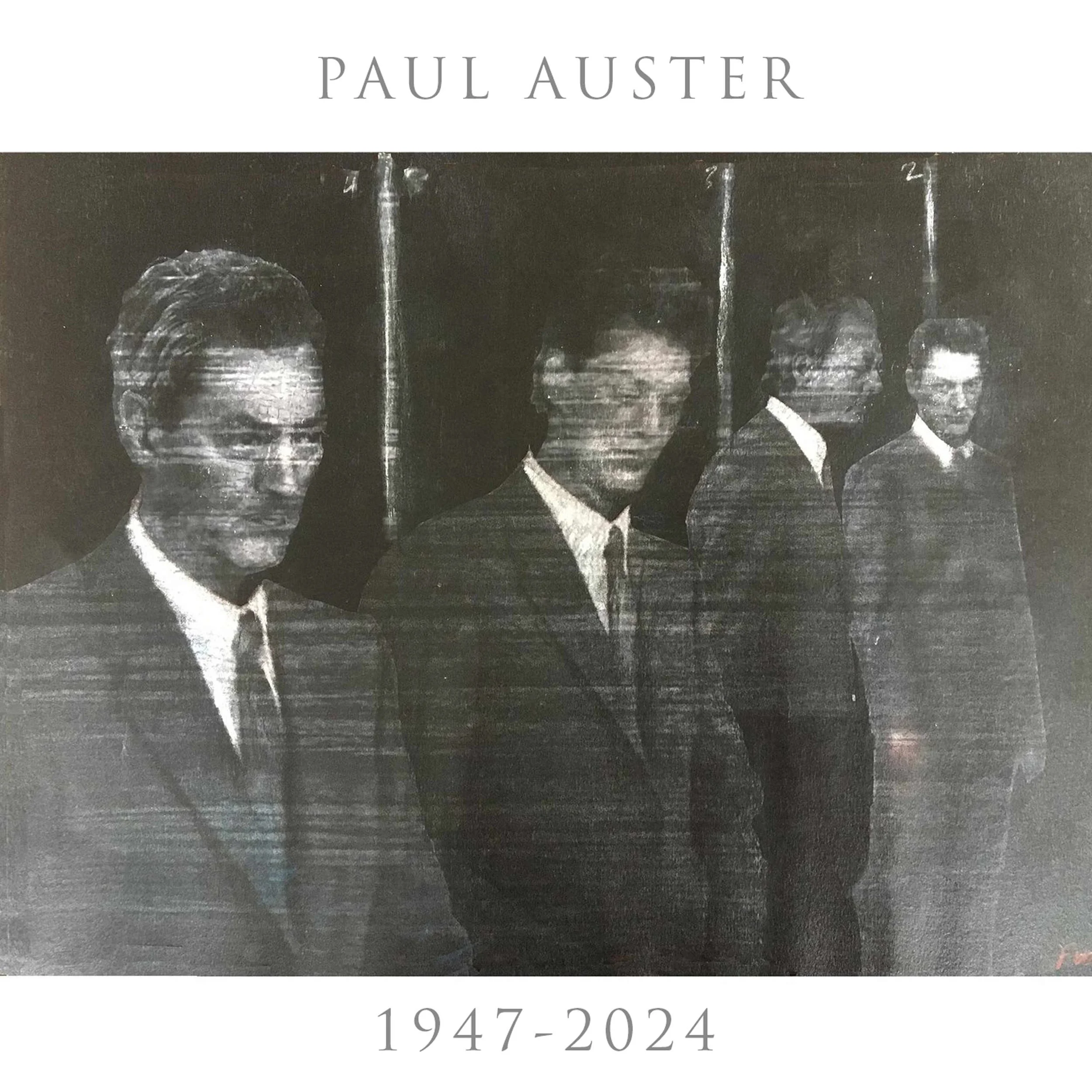

It is said that people never die until the last person says their name. In memory of the writer and director Paul Auster, who passed away this week, we're sharing this conversation we had back in 2017 after the publication of his novel 4 3 2 1. Auster reflects on his body of work, life, and creative process.

Paul Auster was the bestselling author of Winter Journal, Sunset Park, Invisible, The Book of Illusions, and The New York Trilogy, among many other works. He has been awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature, the Prix Médicis étranger, an Independent Spirit Award, and the Premio Napoli. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and is a Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. He has also penned several screenplays for films such as Smoke (1995), as well as Lulu on the Bridge (1998) and The Inner Life of Martin Frost (2007), which he also directed.

We apologize for the quality of the recording since it was not originally meant to be aired as a podcast.

PAUL AUSTER

But what happens is a space is created. And maybe it’s the only space of its kind in the world in which two absolute strangers can meet each other on terms of absolute intimacy. I think this is what is at the heart of the experience and why once you become a reader that you want to repeat that experience, that very deep total communication with that invisible stranger who has written the book that you’re holding in your hands. And that’s why I think, in spite of everything, novels are not going to stop being written, no matter what the circumstances. We need stories. We’re all human beings, and it’s stories from the moment we’re able to talk.

*

It’s shocking how little young people know about the past. I sometimes tremble when I am confronted by this absolute ignorance and, even say Americans, not knowing anything about the American past which is a new country with only about 300 years to talk about. It’s surprising. Or meeting young people, and they say “old movies”. Old movies for a young person is something like Pulp Fiction. And that for them is old. And so they ignore the whole history of movies, which again, it’s a very short history, and it’s very easy to master a great deal of film history in a short period of time if you make an effort to look at the films. But people are not looking back. They’re looking forward. So we’ll see. We’ll see what happens.

*

I like collaborating with people. I find it very enjoyable and at various times people have taken my word and used it for other works. The theatre adaptation of a novel or someone has turned one of my books I’m going to do a little opera. There have been dance pieces based on my work. There was a ballet based on one of my novels. I find that so interesting that one form can inspire someone working on another form to do something. My actual belief collaboration with people, I suppose, well, writing a few songs. I mean literally only about a handful. It’s not something I’ve made a practice of, but the few times I did do it, I enjoyed listening to the results, and the heaviest collaboration I’ve done...of course, is in movies, and that is an exhausting experience to direct film. I can tell you that it’s also a satisfying one. I loved the camaraderie of all the people on the crew, and the actors, and every stage of making a movie is fascinating. I’m glad I had the chance to do this a few times. It taught me a lot about myself and about other people and very important experiences really.

Listen, for some reason, I don’t know why the stubborn old goat has resisted the digital world. I don’t work with the computer. I don’t own a computer. I don’t have a mobile phone. I just haven’t wanted to do e-mail or any of those things. You know, I have a helper, and that’s how you communicated with me through Jen, but I don’t want to do this. And I don’t do it. If I had a job, I would have to participate in all this, but I don’t. So I have the luxury of being able to choose, and I choose not to. I think essentially this digital revolution is a mixed phenomenon it has its positive side and also its negative side. And I’m afraid more and more the negative side to be dominating. And I can tell you there’s nothing more depressing to me than to say go out to lunch in my neighborhood in Brooklyn and go to a little diner a simple little restaurants a sandwich and see a family of four people or six people at the next table grandfather, parents, children. All three generations today they’re looking at their cell phones not talking to one another. It kills me to look at this, and I think the smartphone has made people feel so huge they feel so much the center of the universe by holding that thing in your hand as if they own the universe and it theoretically it connects everybody, but I think in the end it’s separating us from one another. And so I’m worried about it. And then there’s the whole political side of this, and you know the hacking and the the the the possibility for real serious mischief. And sometimes you wonder why governments don’t we just go back to using typewriters and filing cabinets because everything is hackable and used to be a spy would get with a camera a seal one document and then put it back in the filing cabinet But now if you can push the right, you can get the entire correspondence like you know the State Department, or the Democratic Party or whatever it is your trying to do or you can hack into a company the way apparently how the North Koreans hacked into Sony. Everyone is so vulnerable now. So you can see them. And so I’m very very worried about it. I don’t know what’s going to happen. It seems as if there’s no turning back. But we have to figure out how to use this stuff, in a better way. Otherwise, you’re going to really do harm to ourselves.