David Palumbo-Liu is the Louise Hewlett Nixon Professor, and Professor of Comparative Literature, at Stanford University. Founding editor of the e-journal, Occasion: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities, he writes for Truthout‘s Public Intellectual Project, and his work has also appeared in The Washington Post, The Nation, The Guardian, Jacobin, Salon, Al Jazeera, The Hill, Buzzfeed, Vox, and other venues.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You have recently participated in The Battle of the North.

DAVID PALUMBO-LIU

Yes.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And you'll be writing about that as well, I imagine, in this new book?

PALUMBO-LIU

Yes, I wrote one short piece for The Guardian about that conference, which was very pathbreaking. And I've gotten to know some of the people in the Parti des Indigènes and understand what their agenda is a bit. And so, that will be integrated into my book. Essentially, I'm taking a lot of my blogs and expanding them into longer pieces and putting them together and synthesizing a lot of those ideas. And I also, as you know, participated in the day-long conference on the Rohingya crisis in Burma. And that was held at the National Assembly. It was really a very interesting set of participants, from the Nobel Prize Peace Award winner from Iran, Shirin Ebadi to the president of the Bangladeshi parliament to NGO workers and journalists and scholars. It's a very, very terrible case of the genocide in Burma. And again, it was interesting to see an amalgam of people, not just intellectuals, not just diplomats, not just NGO workers, but a whole set of people coming together from different walks of life to try to address this problem. And that's something I'm trying to do again in my own work, is to make contact with people from different walks of life to see what kind of language, what kinds of concerns they're interested in, and so I can match my interests with them. And I was thinking of some of the questions that you raised for me to think about, which are on my mind already, as you know. At the Arab Institute here in Paris, I took my class to a really interesting exhibit. It was the second time this has been put on. And the idea is to imagine what a National Museum of Palestine would look like. And I think it was a couple of years ago, they did one installation and they brought wonderful Palestinian art out and they exhibited it. And then, of course, it was a temporary exhibit and they took it down, and they came back this year and did a whole other set of artworks. And when I took my class through it, there were some obvious paintings and photographs, especially some journalistic work. They really had very strong political content.

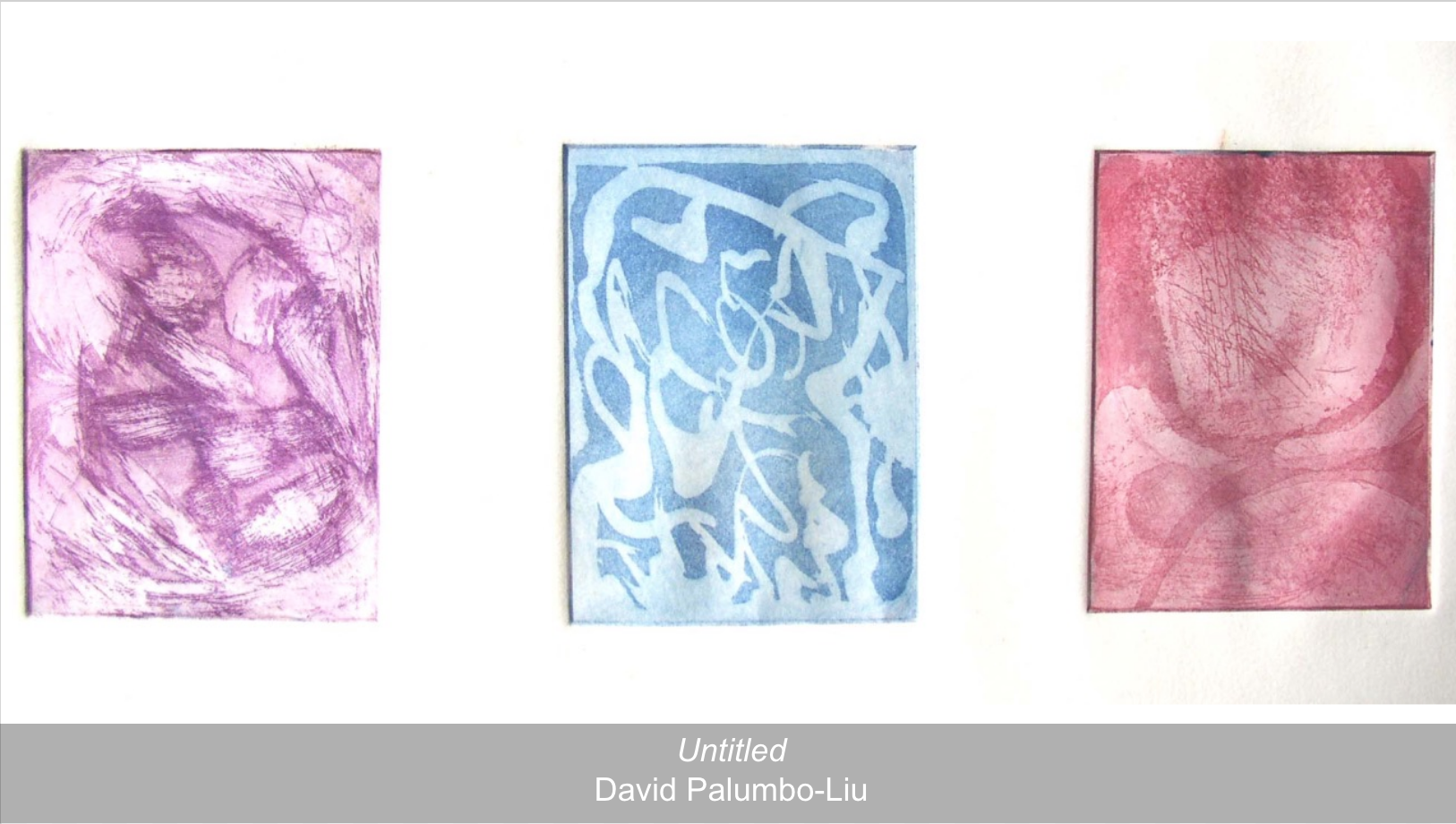

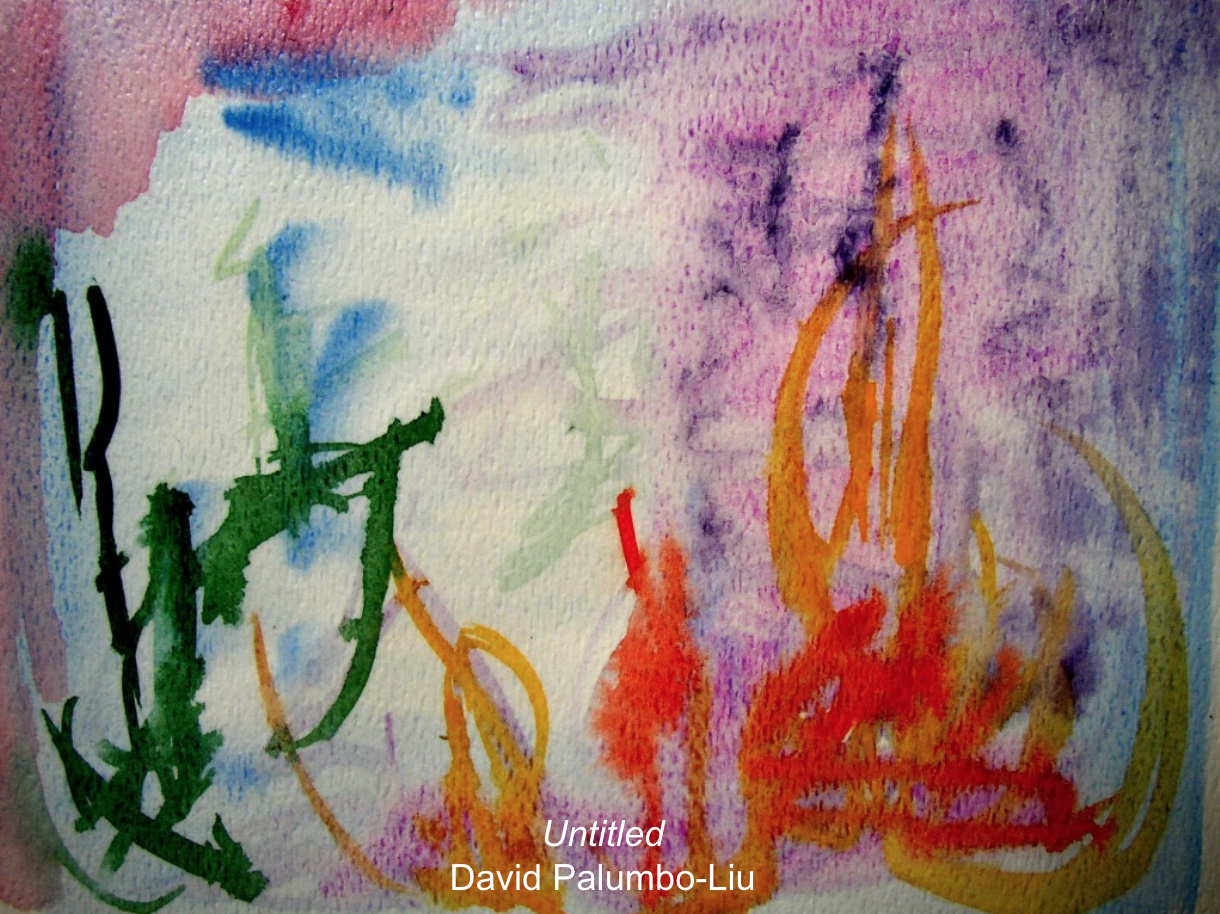

And then there were some that were what one might call universal artworks. And I asked my class, why do you think they combined those things? And I got my class to think about how we tend to reduce people to one cause or one symbol or one thing. And certainly, the Palestinians are in a terrible political and terrible humanitarian situation as well. But yet, precisely their humanity shows through in the artworks that are speaking in a more abstract way just to the fact that what are we struggling for? We're struggling to recognize them as human beings, not just as causes.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

More than just the sum of their struggle.

PALUMBO-LIU

Exactly. That's precisely it. And I was thinking of a line from Mahmoud Darwish, one of the greatest poets, and he said something along the lines of, I'm paraphrasing this, you know, we don't have a homeland, but I hope that my poems can create a space to imagine a homeland. And that's really the key to what I'm trying to do in this book is trying to imagine different ways of understanding political meaning so that we're not simply tied to political parties, elections, statistics, and polls, but trying to become sensitive to the ways that the imagination gives us fertile ground to think of politics and just simply socially being together in unconventional ways that might translate into action in different ways.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And what do you feel are your ethical responsibilities as a teacher?

PALUMBO-LIU

Well, I think they're two. One is to... Well, there's several. One of the main ones is to not tell people what to think or say that one way of thinking is correct but to have them discover it on their own.

In other words, give them a set of options. I think that especially in American universities, which are becoming more and more like pre-professional schools.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Very much a business.

PALUMBO-LIU

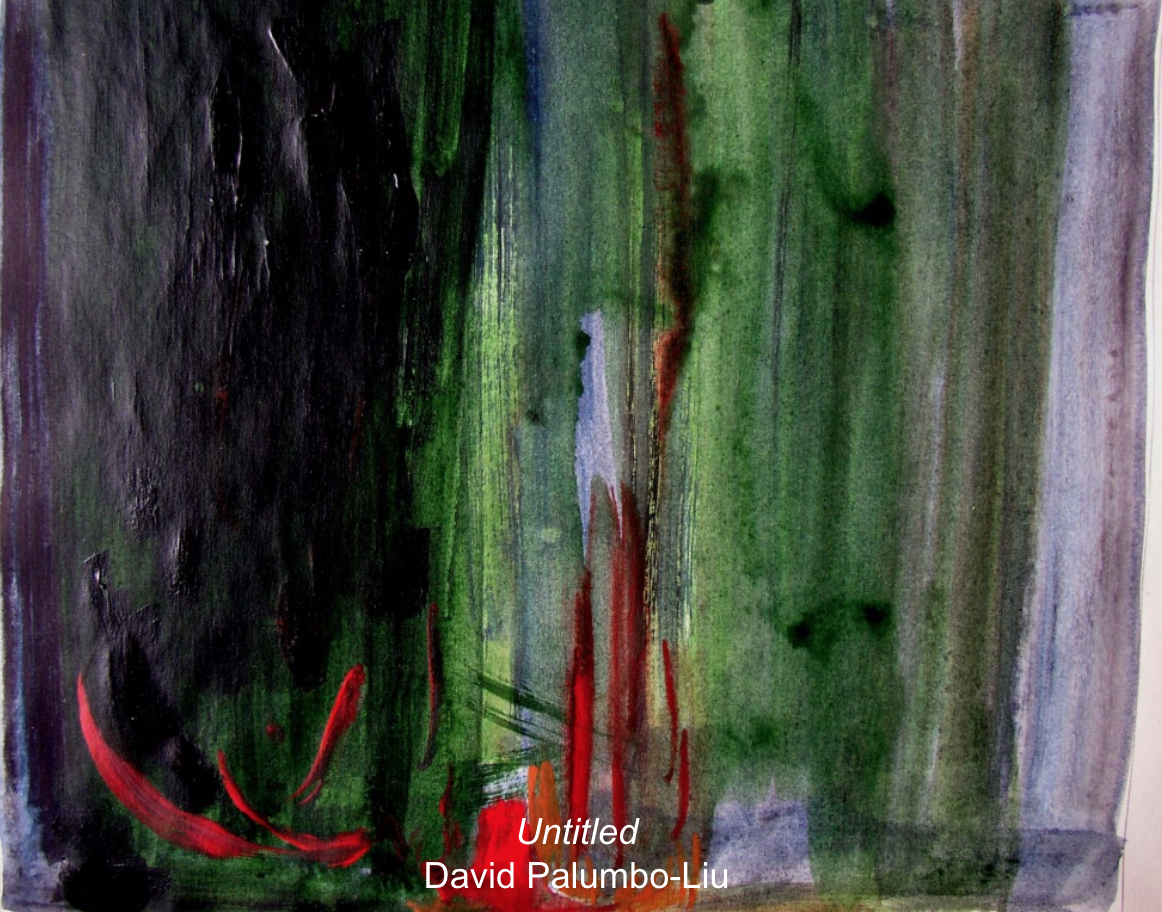

Yeah. Students come in already knowing what they want to do. And so they've already excluded and taken out of consideration all sorts of options, which is exactly the opposite of what a university is supposed to do. It's supposed to give you a broad set of possible ways of thinking about life and training your mind and your talents. And so I like to open that up more for students. And so I will present a political or historical case and say, well, let's try to redescribe it in different ways. Let's try to understand how it's been presented to us. And without setting that aside as being false, examine the foundations of that truth and imagine other possibilities. I think that's the first step for any kind of ethical consideration, is to understand that truth is an assertion and to try to test the viability of that assertion and the conditions that that assertion is made upon. And again, that's where art comes in as being extremely useful is because it shows in a different medium how the world might appear. So I think that's the first thing that I think about in terms of an ethical presentation and a responsibility in the classroom. And also the other thing that I think is really important is to listen, because it's easy just to profess. And, you know, professors love to hear their own voices and have a captive audience. So it's very easy to get to fall in love with the sound of your own voice. And often students become complicit in that because it's easier for them to be passive and not active. And so I like teaching smaller classes. I like to have students discuss things with me and with each other. And so I think that's really important is to listen to what students are saying. That's the reason I went into education. It was to have conversations.

I often tell my students when they say, well, you know, they're not sure what kind of job they want. And I say to them often enough, think of the kinds of conversations that you'd like to have. What kinds of things would you like to put your energy behind, whether it's inventing something or thinking about wise investments or whatever? You know, you're somehow going to be spending at least eight hours of your life, five days a week in the United States talking about certain things. And it should bear some connection with things that you think are important.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes, and it's also interesting because a part of your teaching–I don't know if it's an active part of teaching was something you do on the side–this is bringing students into the community. You spoke about bringing them into art galleries.

PALUMBO-LIU

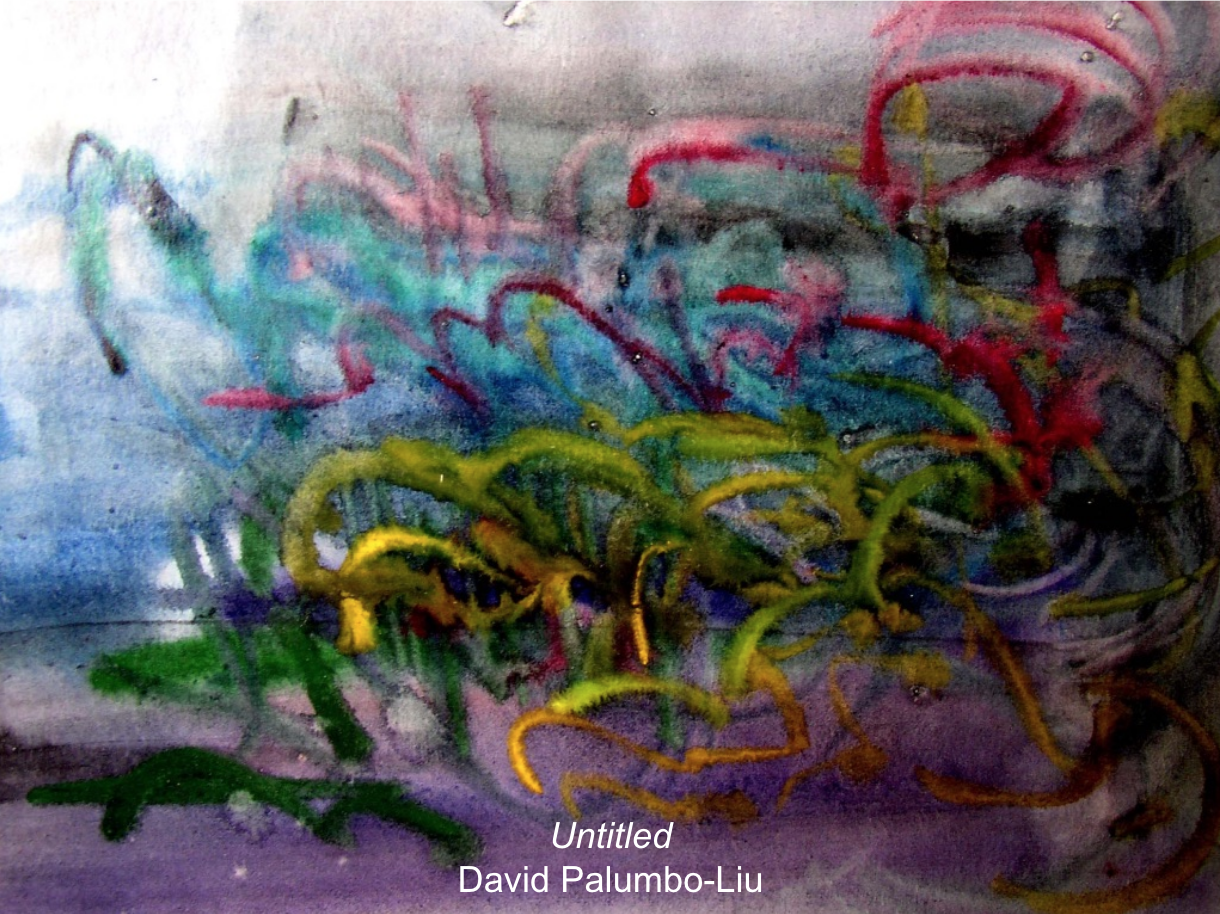

We have in the United States this thing called community-based learning, and it's the idea that you can take a class for credit and you spend half the time in the classroom, and you spend the second half of the time working with a community organization.

And the idea is not to bring the knowledge from the university into these community organizations, which might have to do with health care, education, the arts, but rather, it's a two-way learning process in which you understand the work of the organization. Their challenges, their rewards, and you collaborate with them on a project that, once the relationship is is ended after the end of the class, formally, that it can be sustained. So, there is a very interesting method called The One Hundred Dollar Project, which is that you give students–because especially places like Stanford, students are used to having tremendous financial resources. So the first inclination often enough for charities or any kind of work like this is to go in and throw a bunch of money at it. And so we only give the students a hundred dollars, which is not even one hundred euro. And they have to invent a project that can then be implanted or embedded in the organization and self-sustaining. So the hundred dollars is just to get things going. So I think that helps us understand how the human imagination and the human mind given the lack of material resources can sustain.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this podcast was Chase van Langan. Assignment Editor was Sorella Lark. “Winter Time” was composed by Nikolas Anadolis and performed by the Athenian Trio.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process.