By Mia Funk

I should have loved you when I had a chance. When the time was right and, as they say, all the ducks were lined up, and it would have all been so easy. That small window, open just a crack, but with a crowbar and this thing growing in me–was it even then love?–I could have got down there and pried it open.

Nothing to hide or be ashamed of then, when we were both free. Of course, that’s a lie. We were never really free, but we were both alone in a new city, and so it felt like freedom. I’d lived there once, many years ago, but still enough so that Istanbul was not completely strange. Familiar but unfamiliar. And you liked this fact that we could discover it together, but that I knew it enough, the language through my parents. Though I never told you, I spoke it like a child, you thought me completely fluent, and that made you confident.

Tourists are reckless and lovers are reckless.

We ventured into any neighborhood. Taksim. Sultanahmet. Sisli–what were we thinking walking around Istiklal Street at night? There was no alley or dark, piss-stained place we wouldn’t venture into curious as wild children.

But with our emotions we practiced caution.

I am not the kind of woman to fall easily in love. And not even because I’ve been hurt before, but because I know what it is to be loved deeply, completely. Why would I settle for anything else? Your curiosity troubles me. How easily you fell in love with me? What happens when I turn my back, does this love stay with me or does it fall on the next pretty face in line. And mine is not so very pretty. Once, maybe, I had my moment, but I am older now. When we go out at night–we haven’t even kissed but I pretend like we’re lovers and line my eyebrows in dark kohl to look like a diva. Tragic like the ones I read about in books, tempting you to love me that way: madly, deeply, tragically.

We could stay here for hours looking out at the Bosphorus, which seems to us the most beautiful river in the world. The truth is all rivers are the same. They ebb and flow, it is the wishes that lovers deposit on their banks which makes them different.

I cannot love another academic, I tell you. A professor with a photographic memory nearly drove me mad in my youth. What I need now is someone stupid. Or not stupid, exactly, but not too smart, I tease you, but you see right through my games.

The Games People Play, a book recommended to me by my good friend, a psychoanalyst, lays unread on my nightstand. The title was so tempting, I picked it up many times but end by not reading it. A part of me is curious. A part of me doesn’t want to know. A part of me thinks she knows everything already.

You tell me: take a chance.

You tell me: I need to go away for a conference. I need to translate Derrida into German. It’s not that I want to leave you, but I’m having trouble managing my time.

I don’t want to stand in the way of your studies, be the reason you give up the fellowship at MIT, be another thing you feel you have to manage.

And all the time with all this intelligent talk and all the ways we manage to discreetly avoid this thing hovering between us–just a kiss, I think, but that would be the end of me.

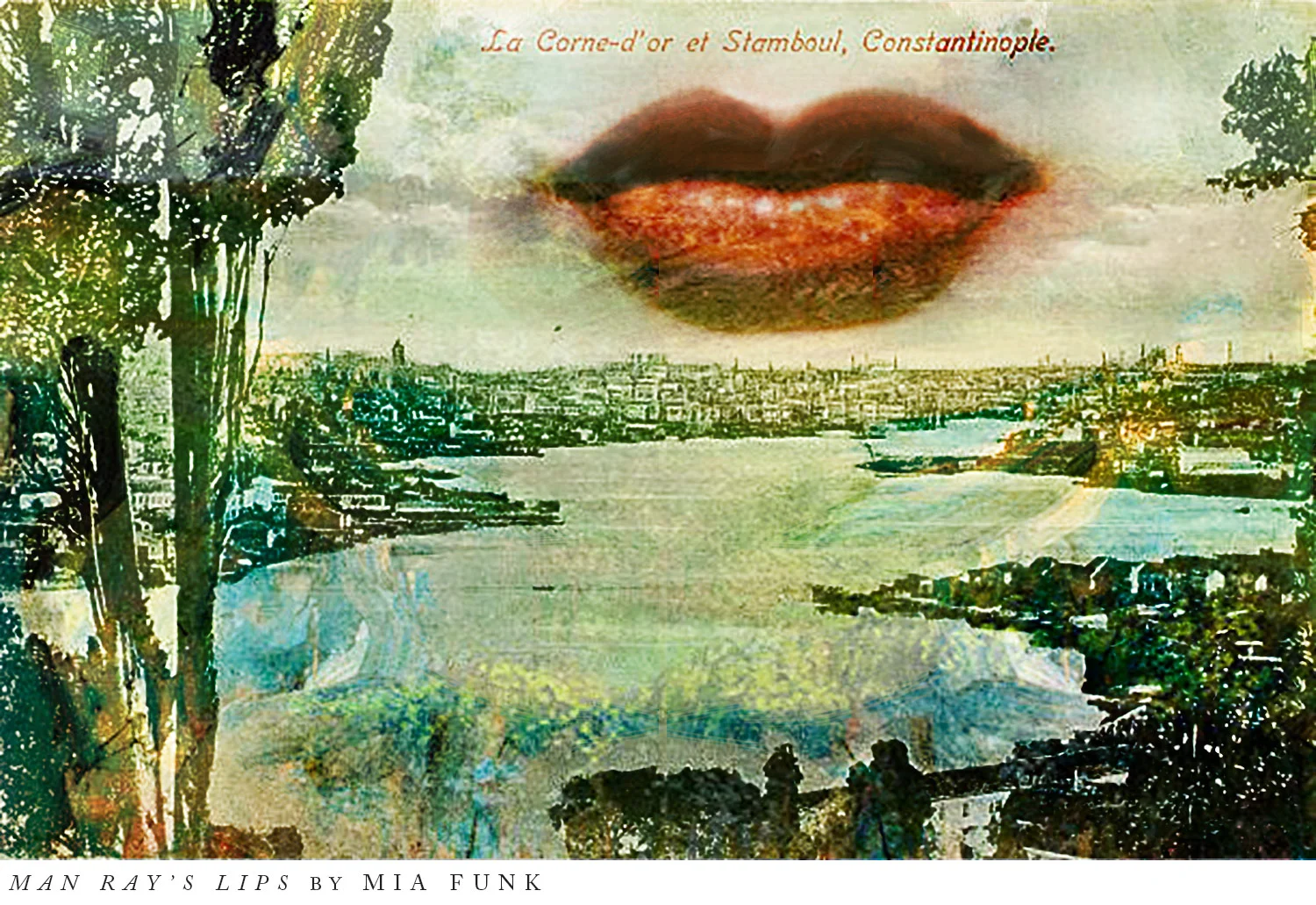

And so it hovers there like Man Ray’s lips, red over the ancient roofs of the city. Wide and calm and mysterious. We pass people dancing and singing drunkenly in the street, but even holding hands is too much for us. We huddle in the doorway waiting for the rain to pass. It is a cliché moment, one set up by God to tempt us. This is your cue to kiss me if you had a clue and weren’t so polite, and so I die inside waiting and waiting for something that never comes.

Constantinople, I love you, you say before you leave for the airport and by this, I know you mean me. You will miss her, Constantinople, you say, but I know what you are really saying.

And with a nod and the tightening of your luggage’s shoulder strap, you carry your heavy burden down the old stones steps to the curb where your taxi is waiting. In a few days, I will repeat this ritual, and I will be back home with my husband telling him about the archives and all the details of my research trip, omitting your name entirely. “Who is this?” he will say, finding your photograph.

“Oh...” the dark kohl is gone from my eyes, and once again there is nothing mysterious about me, and I calmly reply, “just someone I met at the library.”

And my husband, who normally has excellent timing, misses the cues entirely. With his arms and with his mouth, he tries to fold me into a great big Man Ray kiss, never sensing that my lips are lonely and I have left them behind, hovering over a strange city.