曼努埃拉·卢卡-达齐奥 (Manuela Lucá-Dazio) 是普利兹克建筑奖新任命的执行总监。 以此身份,她与评审团密切合作,但她不在评审程序中投票。 她是威尼斯双年展视觉艺术和建筑部的前执行主任,自 2009 年以来,她与杰出的策展人、建筑师、艺术家和评论家一起管理展览,以实现国际艺术展和国际建筑展。 在此之前,从 1999 年开始,Manuela便开始负责这两个展览的技术组织和制作。她拥有意大利罗马基耶蒂大学建筑史博士学位,现居住在法国巴黎。

Manuela Lucá-Dazio is the newly appointed Executive Director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. In this capacity, she works closely with the jury, however, she does not vote in the proceedings. She is the former Executive Director, Department of Visual Arts and Architecture of La Biennale di Venezia, where she managed exhibitions with distinguished curators, architects, artists, and critics to realize the International Art Exhibition and the International Architecture Exhibition, each edition since 2009. Preceding that, she was responsible for the technical organization and production of both Exhibitions, beginning in 1999. She holds a PhD in History of Architecture from the University of Roma-Chieti, Italy and lives in Paris, France.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You grew up in Naples. Tell me about your childhood and how that influenced your imagination. Before you began working with museums and classical art. Tell us about that journey.

MANUELA LUCÁ-DAZIO

So for me being born in a place like Naples helped me absorb and to be constantly open and curious about other cultures, simply because they were part of my own culture. So it's a challenging city, I must say. And it's incredible how you more easily communicate with other people when you are in a place that you feel is a public place, but it belongs to you. It belongs to everyone. It's a space for the community. So this was the first lesson that I learned studying architecture because then you start to read the places in a more organized, scientific way. And I think maybe this dimension passed into my DNA.

LUCÁ-DAZIO

When I started and I had to decide what to do in life - because I was working with museums, in exhibition design, and on the restoration of buildings - and then at some point, I had the chance to arrive at the Venice Biennale and my whole perspective changed. And it changed because I was working with living artists and architects. Until that moment, I was working around Old Masters, works in museums, and things that were there with the aura of history. And all of a sudden I was dealing with living architects and artists, and this was, for me, the most incredible experience. So I decided to leave all the rest, because I was doing quite a lot at the same time, and to concentrate on the Biennale.

And the very first lesson I learned is that we are there for the artists. And when I say artists, I mean also architects, of course. There would be no Biennale and probably no institution, no museum, without the artists. And to be able to deal with the artists, architects, curators, let's say the creative part of the process, you have to develop empathy and mutual respect and trust, but also you have to be very flexible and very decisive and firm when necessary. So it's quite easy to say, but it's not so easy to put it into practice, I must say.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I know education is very important to you. So how do you transmit this knowledge? Architecture is skill, a trade, and an art that has certain rules that need to be learned. As a society, we need to have essential design tools so that we might design a better future, even if we're not ourselves architects or designers. So how do you think we might evolve some of our educational systems to really impart this essential design thinking for the betterment of society?

LUCÁ-DAZIO

I think we have become quite disconnected. We should become more connected to rethink how to communicate and how to learn from the past. And how to use this incredible cultural heritage that we have and how to make it alive and how to translate it into our own times. We want to expand the tools. So maybe to become a little bit more open and imaginative in creating bridges between different fields of knowledge, different methods of teaching and learning, and different ways to transmit knowledge.

We need to invest a lot in education. Education of the future practitioners, but also the education of future clients. And by client, I don't mean only governments or investors. I mean each one of us, we should become responsible for our demands to architects and to whoever is involved in the building process. And this is why I see so much that education is the main tool to get there because we have to educate ourselves, first of all, and prepare the future generations. And the extent to which, as you say, it's not just beauty, but bringing people together in spaces that are inspiring because it can be a radical thing. It could create societies that are more equal in terms of public spaces. And right now that's being unequally distributed.

*

We are living in a world that is extremely complex and complicated. So our lives have been halted, regardless of any geography, as a result of growing inequality (political, social, economical), and so on. We live now in a moment of deep shift. And I think that decolonization, decarbonization, social and environmental injustice, and gender equity, these are all terms that belong to daily vocabulary now. So we have to face and address these issues from both a personal and professional point of view, whatever our profession is.

We should all learn to be sustainable in our daily life and find the beauty in what proves to be sustainable. And we really need to start shifting our way of looking at things because sometimes sustainability, which is a priority right now, doesn't really coincide with let's say the cheapest solution or the best economical solution. But we have to decide our priorities. So the priority now is sustainability. We have to start to think about that. If I think back to the most recent winners of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, I can see a lot of really groundbreaking innovative practices being brought to the forefront.

*

I think the Pritzker Architecture Prize has the power to foster and enhance the discussion on the one end. And on the other end, it has also the power to involve a more global discussion. So it's not just limited to architects because ultimately architecture is what we live in and we use every day of our lives. So all of us should be involved in this discussion. It's really a common responsibility where the architect, who from my point of view is the translator and the interpreter and the catalyst of all this. So we should rethink what sustainability is and combine the art of architecture and the benefits to humanity and the built environment. This, I think, is a lesson for every single architect from all over the world.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

There is natural intelligence or the things that have been passed on from generation to generation. So there is this deep cultural memory. And that's what architecture imparts, that sense of continuity that bridges the generations, that brings us in touch with the past as much as it brings us into the future.

LUCÁ-DAZIO

I think history and tradition are super important, and this is the point because each generation is sort of translating to the next one. There is almost never a gap. So each generation is in a way interpreting and hopefully also adding something to what is transmitted and continued. And so this is why I think the younger generations now have tools that we didn't have at their age. They are probably able to interpret. And now we go back to the whole discussion about the necessity for sustainability and attention to social and environmental injustice. They probably have a vision or perspectives that we don't have. So in a way, in this transmission, we should be able to learn from them too.

*

So from my point of view, a prize is not just to establish the most beautiful building, the most expensive building, or the tallest building in the world. It's rather to foster the discussion to bring forward critical points to be discussed. To bring forward contradictions, to really enhance the discussion about what is relevant for our society or for society in a specific moment.

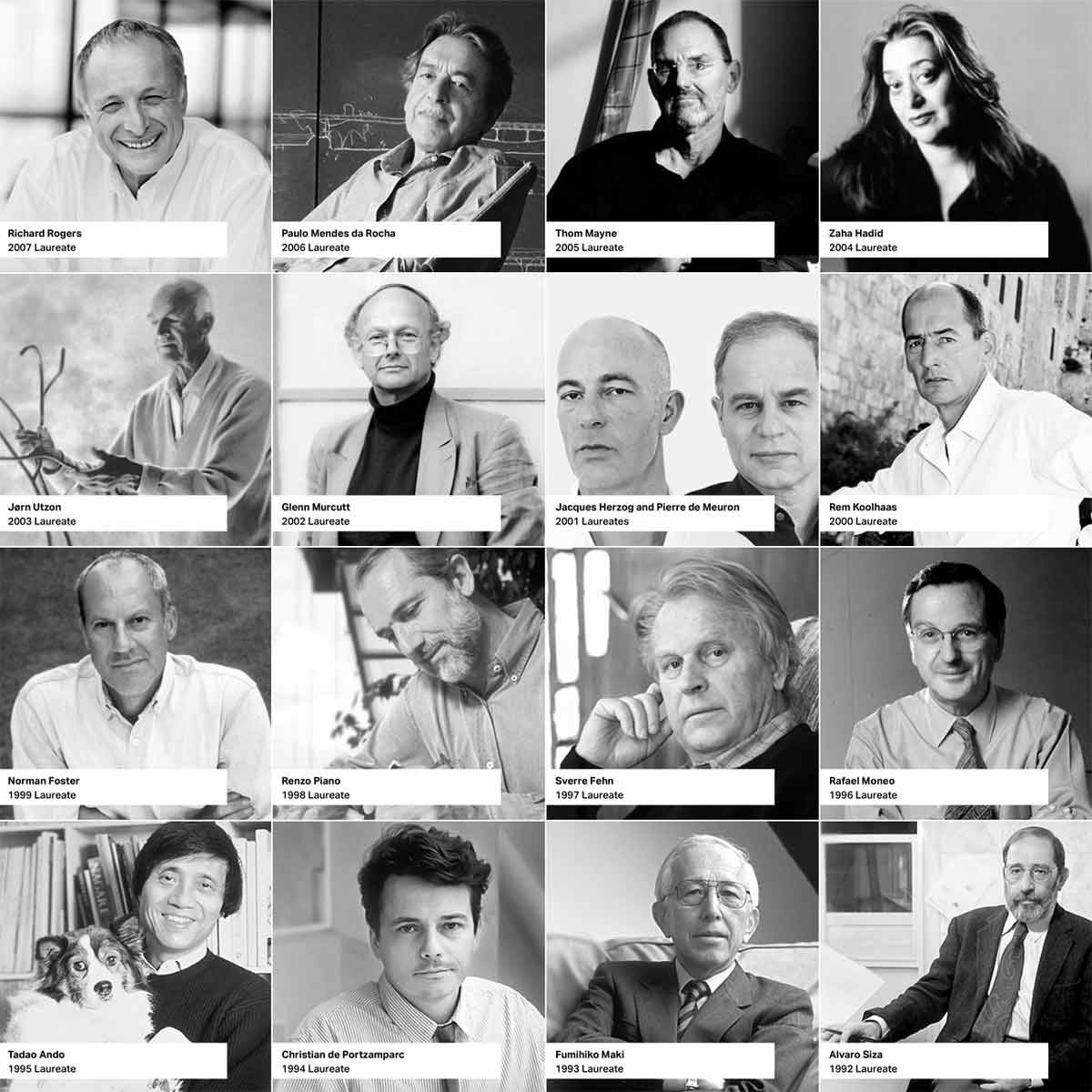

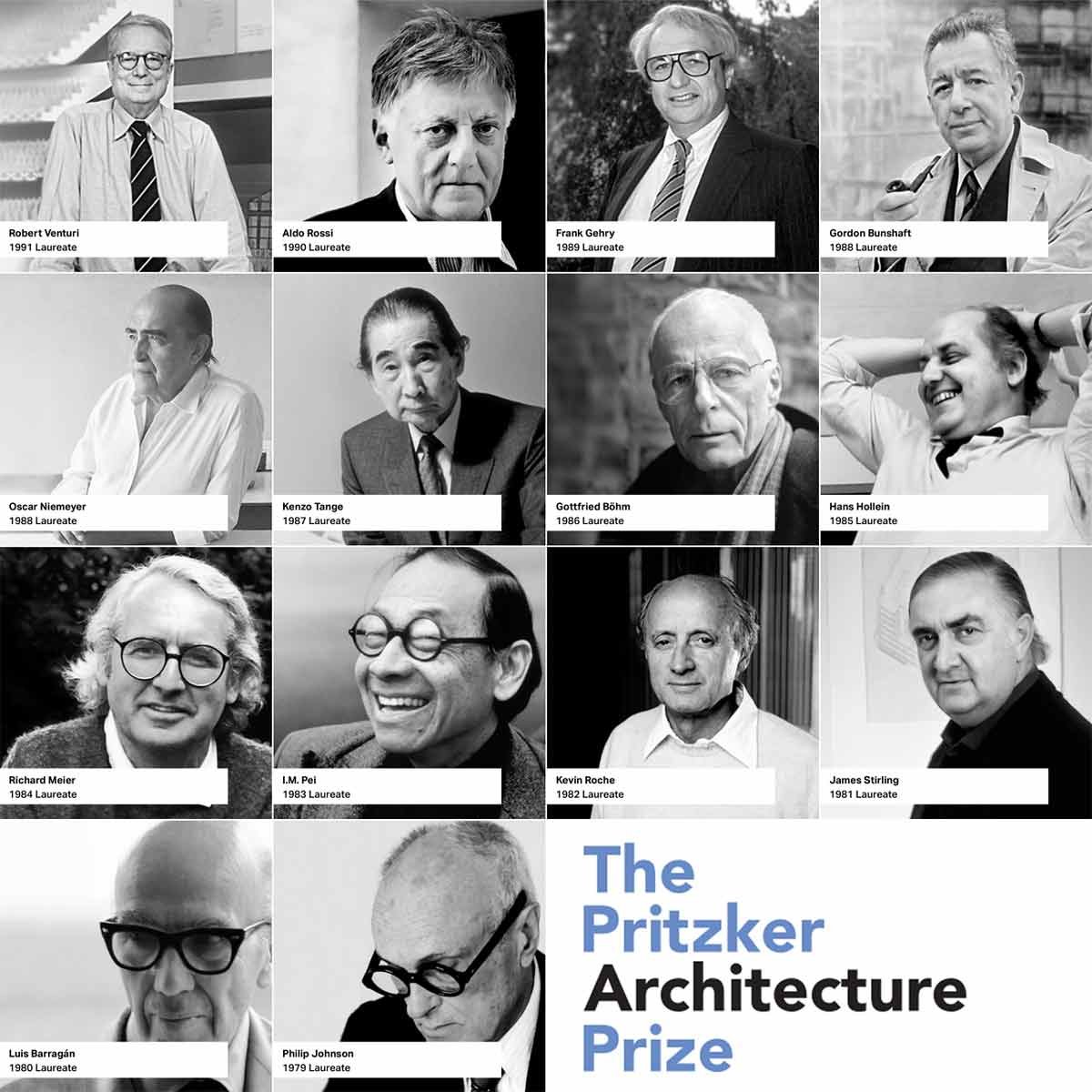

So this, for me, is the role of a prize, to highlight critical issues and to foster the discussion, to face them, and to find solutions, to find new paths. So in the case of the Pritzker Prize, the mission has been very clear since the very beginning. So it's to acknowledge a living architect or architects for a body of built work that has produced a consistent and significant contribution to humanity and to the built environment through the art of architecture.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

We're seeing more leaders who are women. There have always been strong women, however, when you started out, it was rarer to find women in the roles you took on. So who were some of your role models or early teachers?

LUCÁ-DAZIO

There are a lot of women who influenced my life, starting with my mother. My mother is of those women who managed the house, our lives, our family. And she's still there with incredible intelligence, curiosity...She reads, and sometimes I have conversations with her about themes that relate to the Biennale, to art, to architecture, and I'm always surprised. How can she know all this? And sometimes there are even things that maybe I, I knew quite confidentially in my job, and I said, "How did you get to know that? This is not public?" She said, "Well, I read this in this newspaper, this in the other, and then I put the things together. It's quite clear." You know, women have this power to analyze, to observe, then to elaborate, and act.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

As you think about the future, education, the challenges we face, and the importance of the arts, what would you like young people to know, preserve, and remember?

LUCÁ-DAZIO

Well, this has a lot to do with this chain of transmission of history and knowledge. So all this is a very important heritage that we receive from our parents and we transmit to our children, grandchildren, and future generations. So I think we should be able to transmit them to be a bit more critical about what we transmit and try not to teach in a sort of dogmatic way and let them be free to interpret and understand and add to the history without the burden of stereotypes or predefined concepts.

So they should definitely look at us, not necessarily learn or imitate us, at least not a hundred percent, to use the incredible heritage that they receive, but with some degree of freedom and without borders.

Photo credit: Anselm Kiefer, Sylviane Sarfati

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this episode was Yanhan He.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).