How does the mind influence the mind? The mind cannot function without memory. And memory is just the mind aware of itself. So how do images tell us how we see and who we are?

Ralph Gibson is one of the most interesting American photographers of our time. His international renown is based on his work, which is shown and collected by some of the world’s leading museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the J.P. Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the Creative Center for Photography in Tucson, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, and the Fotomuseum Winterthur in Switzerland.

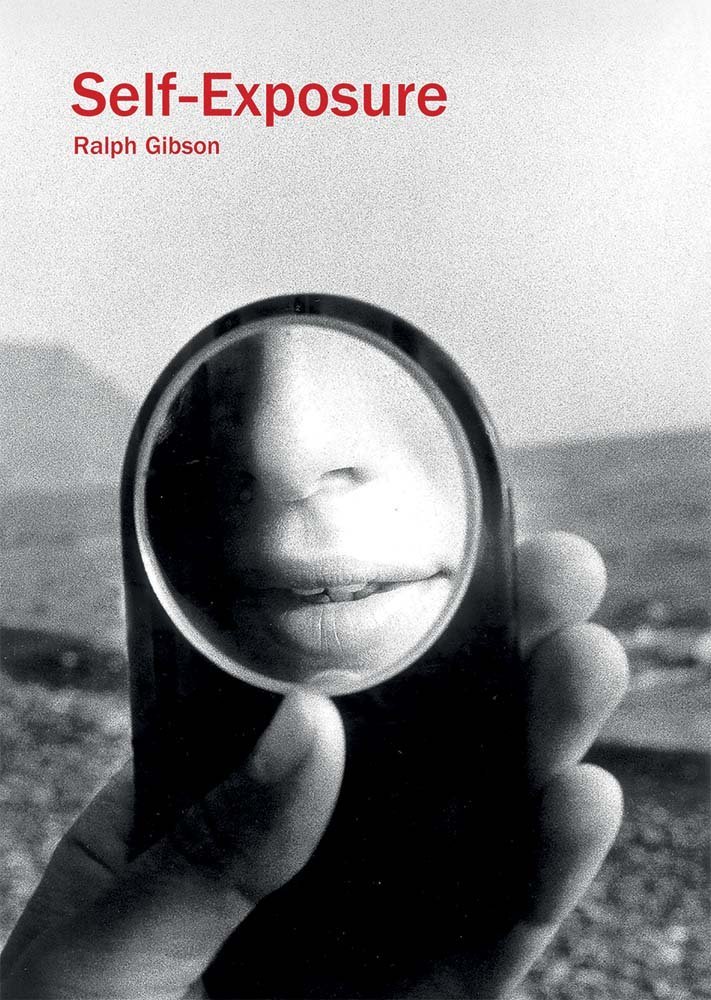

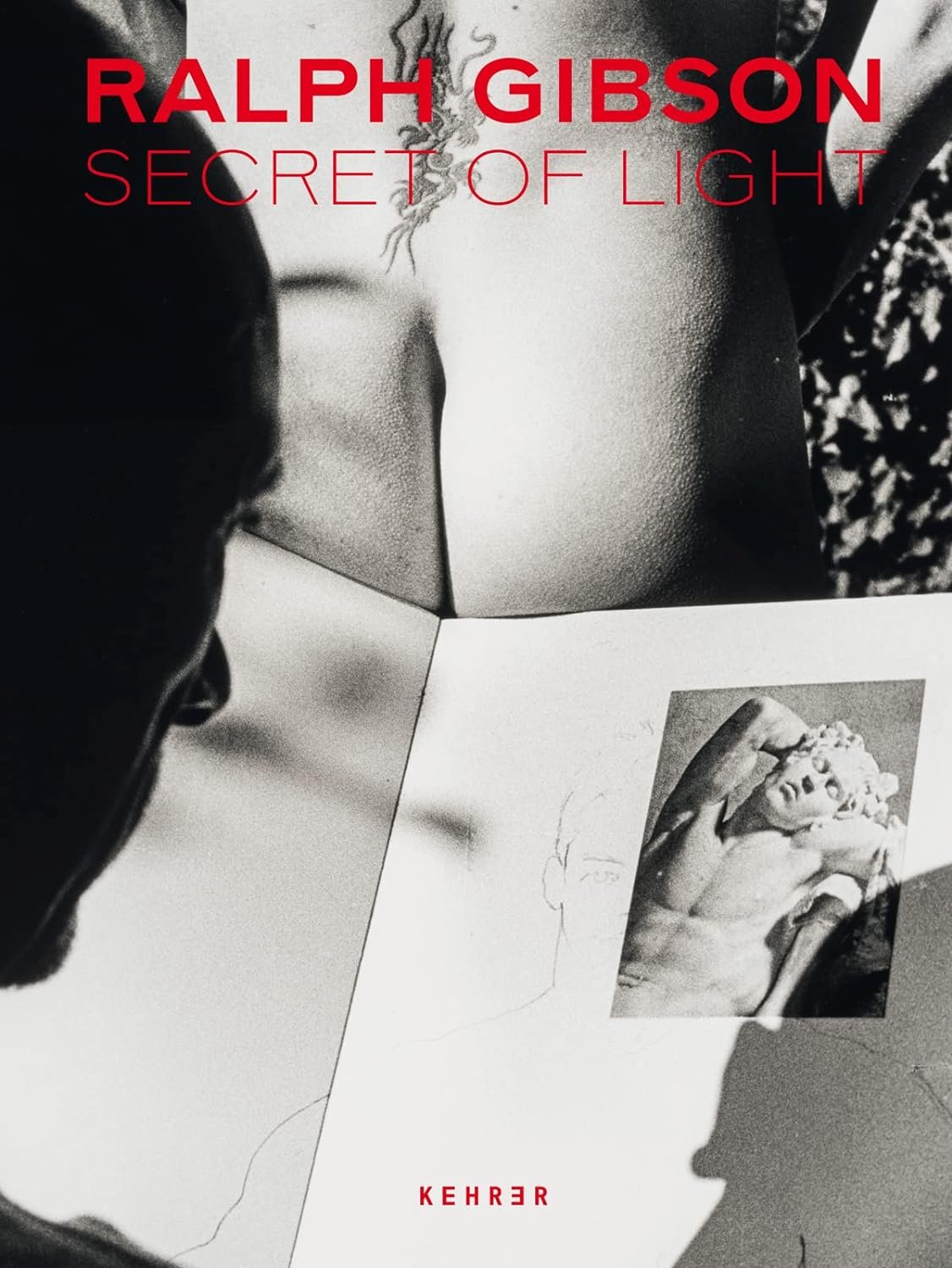

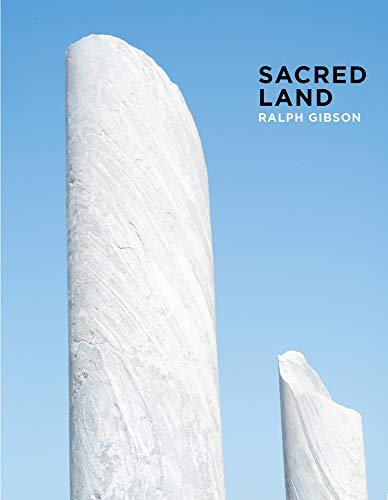

Gibson’s works reveal a meticulous aesthetic and visual territory edging on the surreal. His recent books include his memoir Self Exposure, Sacred Land: Israel before and after Time, and Secret of Light, which accompanied his exhibition at the Deichtorhallen House of Photography in Hamburg. He is a Leica Hall of Fame Inductee and has been awarded the French Legion of Honor. In 2022, The Gibson | Goeun Museum of Photography devoted to his work opened in Busan, South Korea.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So the instinct to capture images or to make music, is it some sense to make them a part of you? To understand your times? How has photography helped you understand the times you've lived in?

RALPH GIBSON

The way I measured time for a very large part of my life was I was always in preparation. I remember as a child I was preparing to make my first communion, then I was preparing to go to junior high. There are always these lapses that existed ahead of us, where we were progressing through time predicated on noteworthy events. So I was always functioning as though there was going to be a significant event, which occurred in some kind of concept of the future. And that coincided in parallel with the fact that when you're young, you feel essentially immortal because the idea of being old or dying is so abstract. It's so far away.

So now that I'm in this phase of my life where all I'm interested in doing is maintaining my health, doing my push-ups, and profiting from as much time as I have left. Because now I'm at the very peak of my powers as a photographer. I'm getting pictures much faster and in greater ratio, and I'm moving through the experience at a rate that I always had yearned towards. And in terms of exhibitions and publications and all that I had everything I wanted when I was 40.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

When I look at your photographs, one thing that you have been very much dedicated to is the vertical horizon. And so that seems to indicate that there are things going on at the edges that we don't see. And what I like about your photographs, and I think of it as a signature of your style, if this subtraction, having this vertical horizon, this pillar, it has this element of voyeurism. It's almost like looking through a doorway with that sense of discovery.

GIBSON

I've never wanted to be invisible. I'm voyeuristic, but in a purely intellectual way. I would suspect the reason for functioning in a vertical format is because the horizontal rectangle is the proportion of all narration, all visual narrative in all society now. In my case, the content is when I get my vision sufficiently stimulated to where I can perceive the corner of this desk with sufficient clarity to render it in some sort of monumental way. I want to make pictures of absolutely nothing purely based on the force of my perception and the power of photography.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Since writing your memoir Self Exposure, are you still keeping journals? What are you writing?

GIBSON

I am more interested now in writing on aesthetics from a theoretical basis. I find I'm able to express certain things that I'd always wondered about on a purely intuitive level. And so that's the nature of my writings. I have a book in the works entitled Theorem, which picks up from that series that you're familiar with, the vertical horizon and nature object things I did after that. They're much more based on theory of perception, theory of socially defined shapes, theory of cultural applications to how we perceive. And, you see, I can express le ciel. I can express the sky: the two different languages, same sky, slightly different.

There is a difference when you say il cielo or the sky in Italiano. You see it? The emphasis, the sound of the word produces a response that impacts our perception of the object being described. So if the word sounds slightly different, the object is going to shift in an interesting way, it doesn't have to be positive or negative.

It's just always interesting to me how think of it, which gets us closer to a musical construct. Because musical is nothing. Music is purely abstract sound capable of defining the undefinable. And it also happens to be a language that's universally spoken. We could play certain pieces of music in any society in the world and it would be to some extent or another perceived, understood. I recently read that there's never been a people that didn't have music. And that can be a very small group of people. It doesn't have to be a gigantic society like Asian or Caucasian. It could be a small splinter group somewhere.

Ralph Gibson has photographed the beatles, Lou reed (with whom he also made the documentary red shirley), laurie anderson, and created album artwork for Joy Division. Gibson composes and plays his own music.

The great photographer Ansel Adams left his negatives to the Center for Creative Photography with the understanding that people could take them and print them and reinterpret them. I think that probably more what occurs in my case is that, years ago, I observed that you could take a fashion photograph, a great Man Ray fashion photograph or something, and 25 years later it was art. It was no longer a fashion concern and Claude Lévi-Strauss the great social anthropologist has made this sort of thing clear: Society changes and with it the context through which we observe something has changed as well. So, quite possibly, the way this curator Sabine, she was younger than I. She's probably in her forties and, Isabel, they both did their thing. They would see it through a different set of filters, you know.

I like the way, for example, we take the work of recently-deceased artists like Warhol or Basquiat. Recently, there was a great show over there, which I was in town for at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. And every five years or so, their importance doubles as artists. It is not just the price of the painting. It's the nature of the work and how it impacted what was before it and what came afterward. And we're all amateur historians, all art historians, all our lives. And we continue to feel this sort of thing. Obviously, I remain obsessed with Cy Twombly, whom I think is ever, ever more important. And now there's an interesting Anselm Kiefer show across the river here I'm going to go see. And so I like the role of art in society and my relationship to my society and to art in my society. And, of course, being here in France, which is a little bit different because all things here are all French. And we see them through that matrix. Now I'm interested in this phase of my life and how does the mind influence the mind?

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

As you say, art creates a kind of immortality. One lives on, and it shows people what's important. And so I was wondering what your reflections are on the importance of the environmental humanities in terms of engaging and telling stories?

GIBSON

I was fortunate to be able to visit the original Lascaux Cave in the Dordogne. And in any of these paleolithic caves, we find there are certain themes there that seem to be, as long as humanity has been on planet earth: there's always been war, there's always been migration. There's always been a search for God, a form of worship, and there's always been a fear of the apocalypse, the end of the world, which if you open up Paris Match tomorrow or the New York Times on the front page, you'll find those four subjects are still being addressed.

Now, we're talking about BC up to today. Now, of course, things are moving much faster now than they did 40, 000 years ago. But I think that capitalism, which created much of this pollution, will find a way of sustaining itself in cleaning up all this pollution.

*

I have asked two generals and four diplomats why the governments of the world are shifting to the Right. In Europe, they all gave me the same answer at four different times. In Europe, it's because of immigration. And in America, it's because of those left behind. Les laissés-pour-compte.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You’ve said you're very interested in how the mind affects your life, perception, thoughts, and memory. We’re all thinking about AI now, and it seems to me the big difference besides not having a body, is that AI gets fed everything, so potentially it has every memory. So it doesn't have a self, it can’t compete with artists like you because it doesn't have your memories. What are your reflections on AI and the new technologies?

GIBSON

We'll go back to my origins. In 1950, my father was unemployed. Hollywood shut down because television had just arrived. And they said, "Oh, the movie theaters are going to close. Until they started coexisting and making films for television. Now, I believe that AI will be an incredibly useful tool. Humanity has endured primarily because of its inherent characteristics. I see things like NFTs and AI and Spotify and file sharing, and there was a time when I moved to New York where I could drift through the empty museum galleries of the moment, and have my epiphanies. Now you go to the same museum, it's like the Tokyo subway. You're, you know, it's a bunch of sardines. That's what's happening because there are too many people in the world for the delivery system to any longer be affected. Museums are delivery systems. We're moving into a world of the private museum now because the great collectors are building their own museums.

I am happy to report since I've seen you, I have a museum in South Korea in my name. So, you know, I'm funneling, channeling, putting hundreds and hundreds of prints into this museum in Busan in an attempt to personalize the situation, but by the time you've got eight billion people living on the planet Earth for a hundred years, which I plan to do. There's a lot of people like me. We know that people are living longer now thanks to medicine and nutrition.

I do tend to think that with file sharing, more people are listening to more music than ever before. You would have previously had to put a Tower Records on every street corner in order to effectively distribute that much music. Now, with NFTs, obviously, I, as the artist, as the audience spreads for a work of art quite often the content goes down. You could have a photograph and sell the original print and have 100 percent of your attention, or it could be reproduced on the cover of the New York Times at 72 dpi, 3 by 4 inches, and you'd get some of it, but you wouldn't get the whole thing, but a million people would see it. Now with the digital situation, working digitally, if the image stays in that digital space permanently, the only real shortcoming is the excessively bright, heavy saturated screen on your computer that tends to exaggerate things a bit.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So I think that your autodidactism has actually been a gift. Last time we spoke, you said you hadn't completed your high school degree, which is, I think, a matter of pride? So you've always been teaching yourself. You've had certain mentors when you worked for Dorothea Lange, Robert Frank who you worked with on two films. So that's kind of learning outside of the classroom. And I think that it serves you well because you had to find your own way.

GIBSON

Well, you know, everybody does. In that book, Self Exposure, one of the things I did realize as I was writing it: all autobiographies are chronological and anecdotal. That's the way they unfold. And I realized that there were certain decisions I had made along the way that were crucial. And there was really only a handful of them. But I was very fortunate because I had that initial desire to be a photographer. I don't even know if it was a desire. I think it was something much further beyond that. I would have to say it was more of a...I didn't really choose photography, it sort of chose me, you know. I mean, nolo contendere. I just did what I knew I had to do. There was a sense of devoir, you know, you just do it.

I wouldn't be able to effectively delineate where my life ends and photography begins. They're one and the same. If my eyes are open, I'm seeing. If I'm seeing, I'm essentially in that valence within which, or from within which come the images.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producers on this episode were Sam Myers and Camila Quintanilla. The Creative Process is produced by Mia Funk. Additional production support by Sophie Garnier.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).