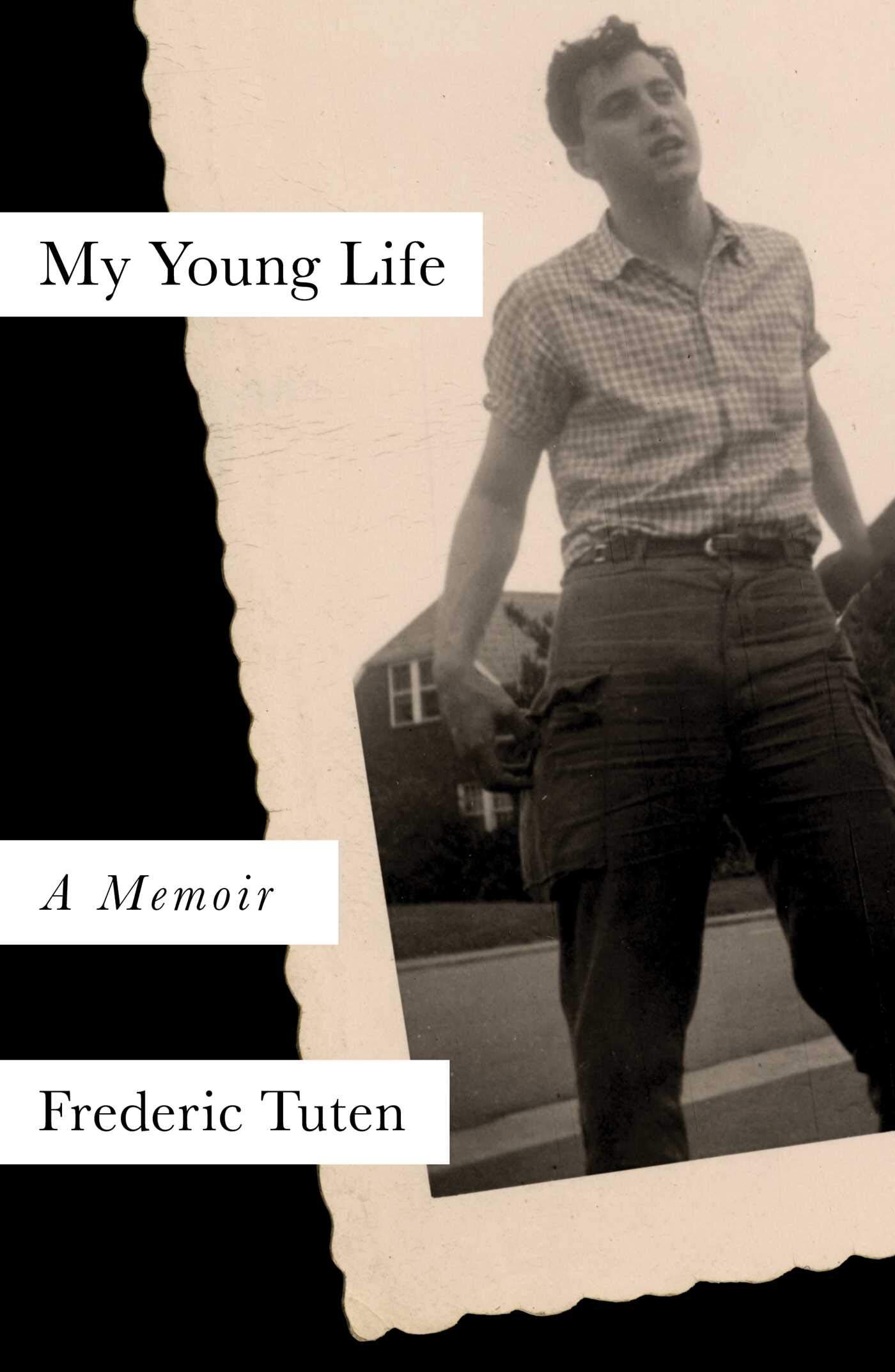

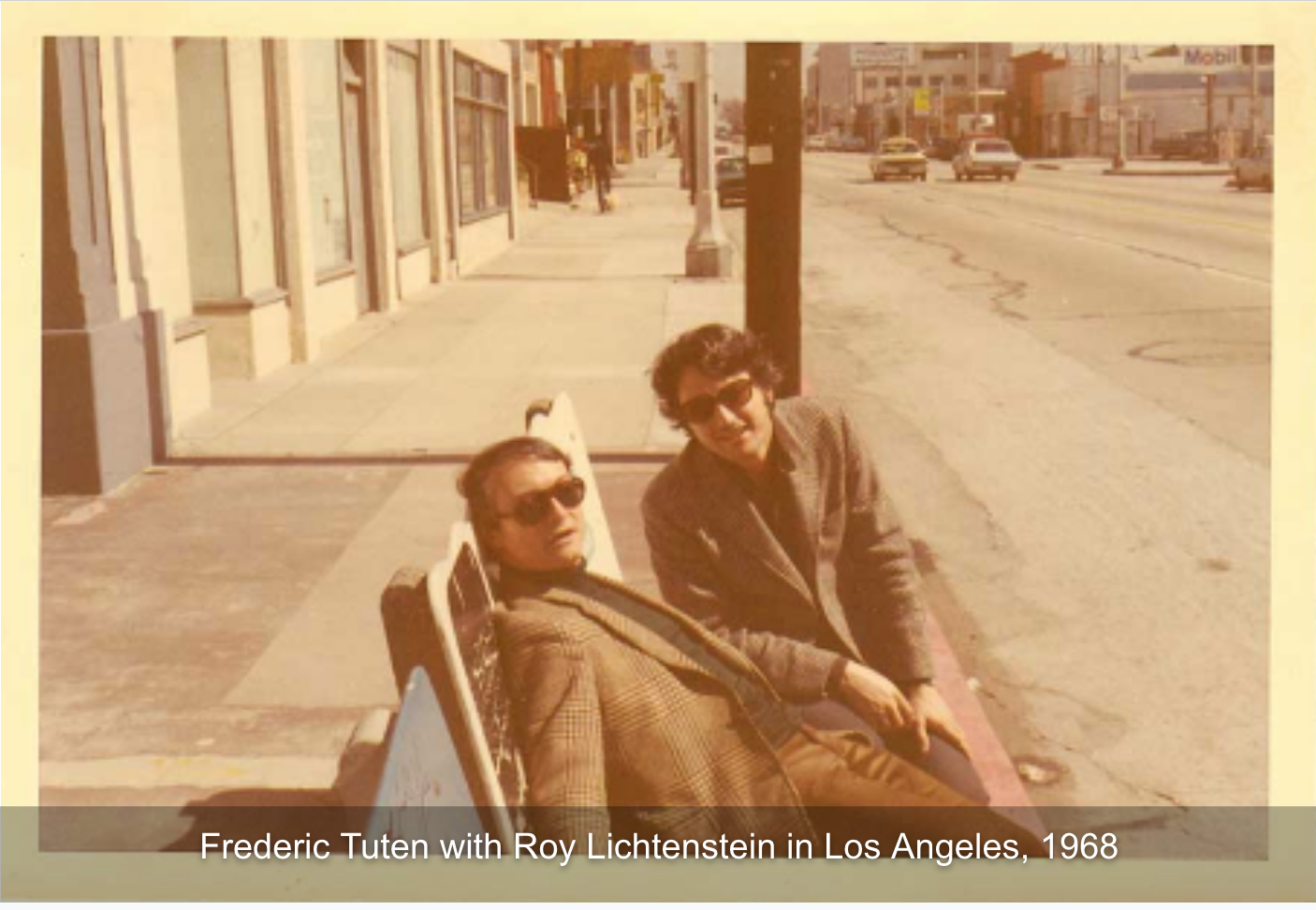

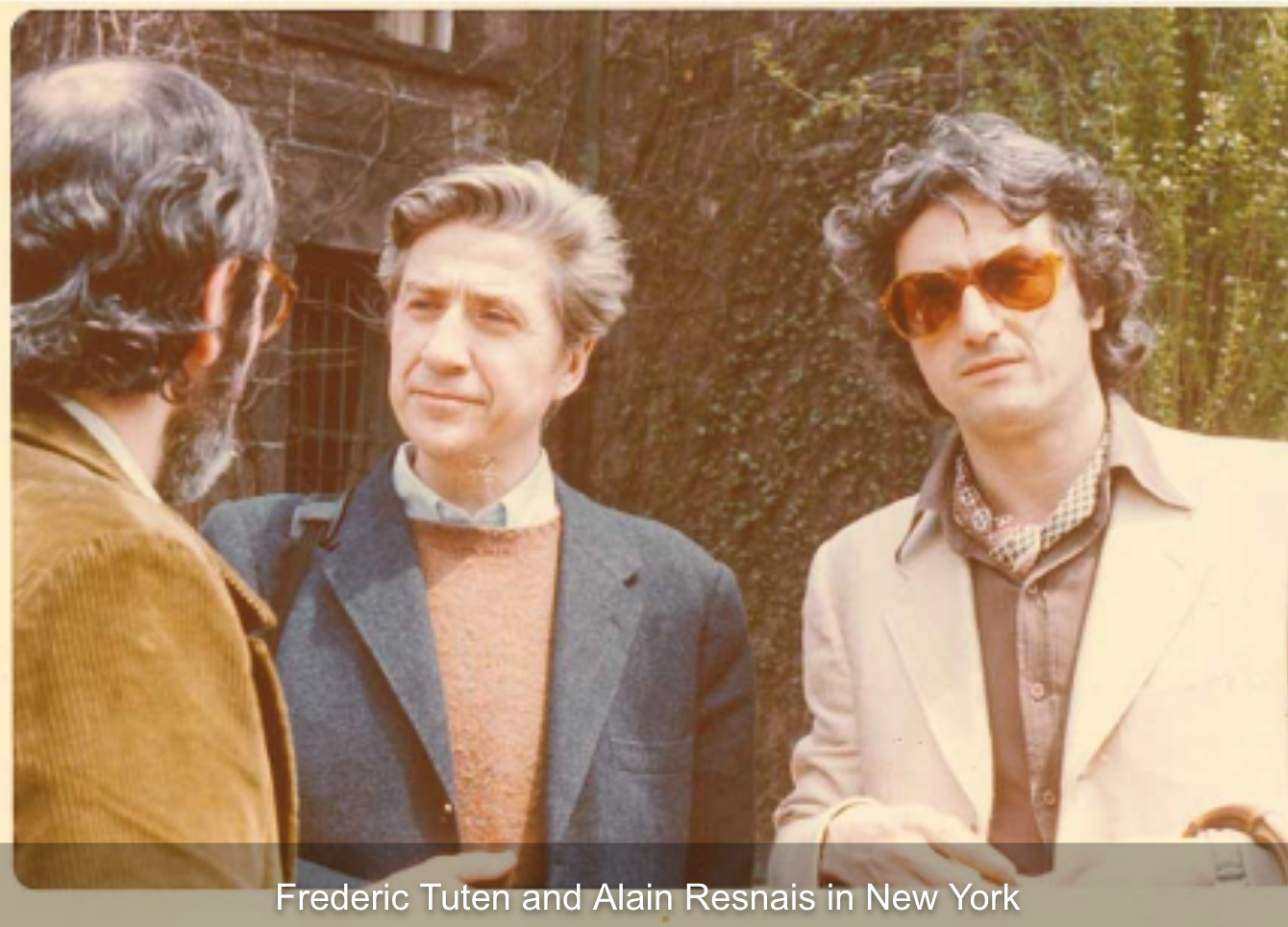

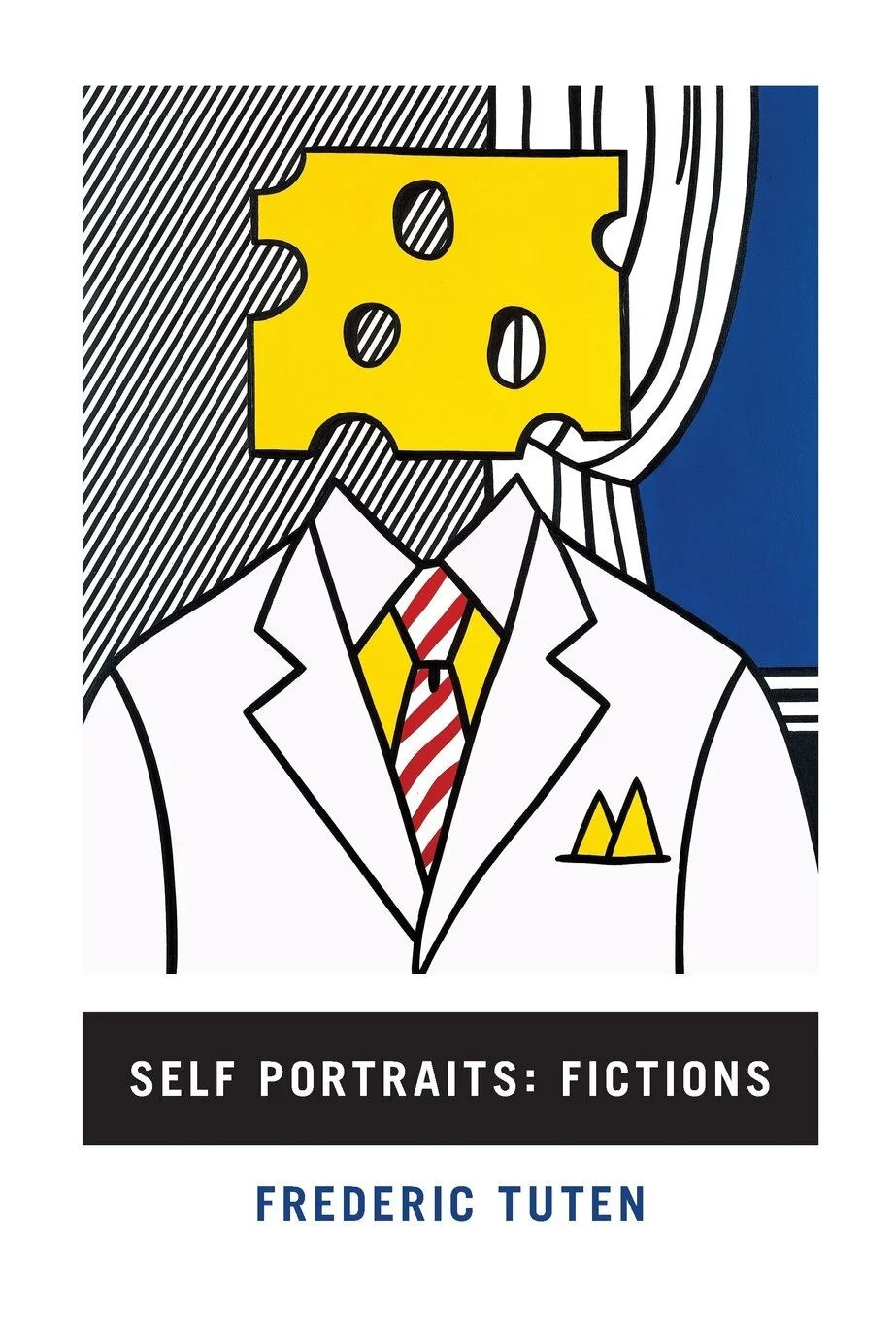

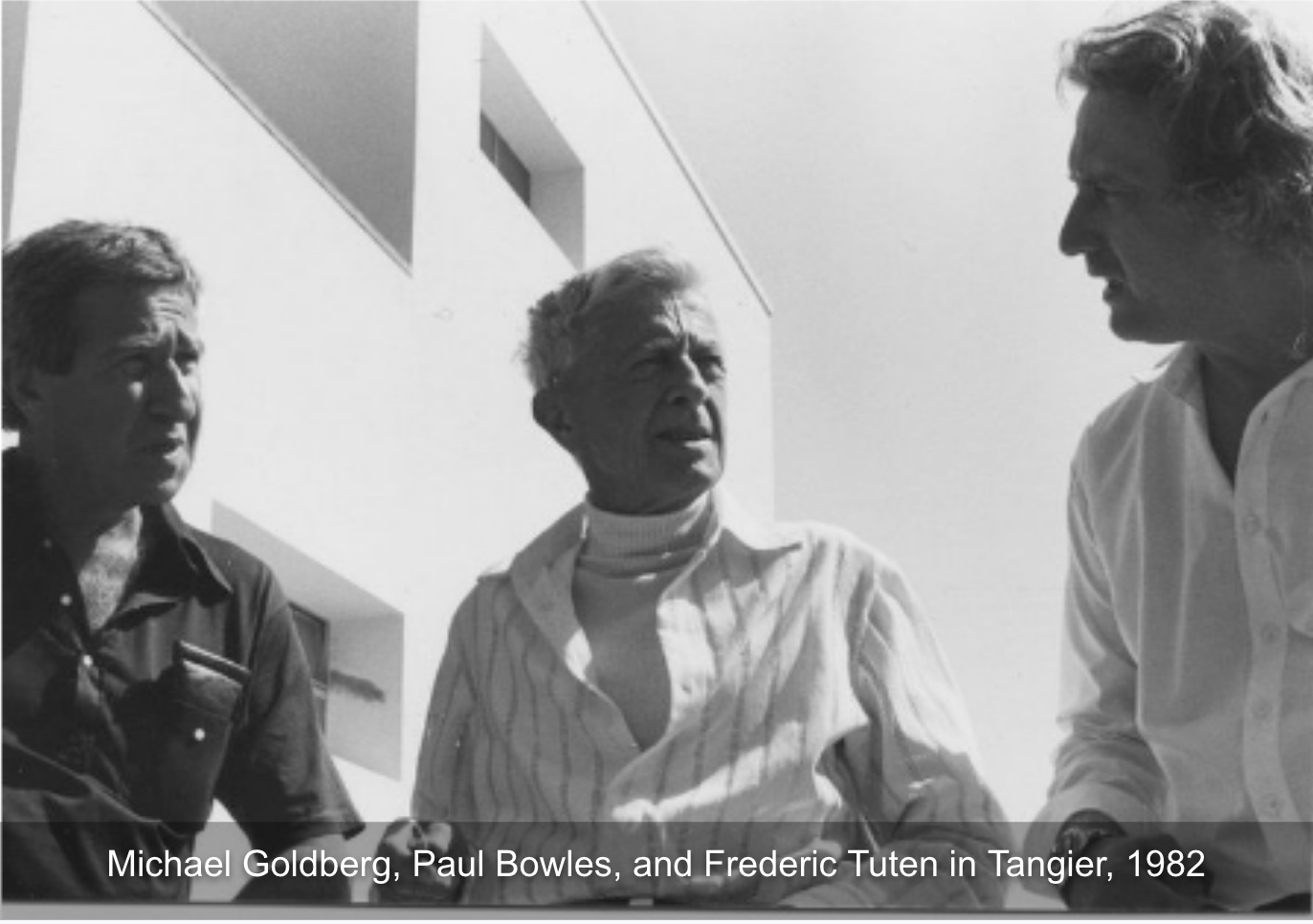

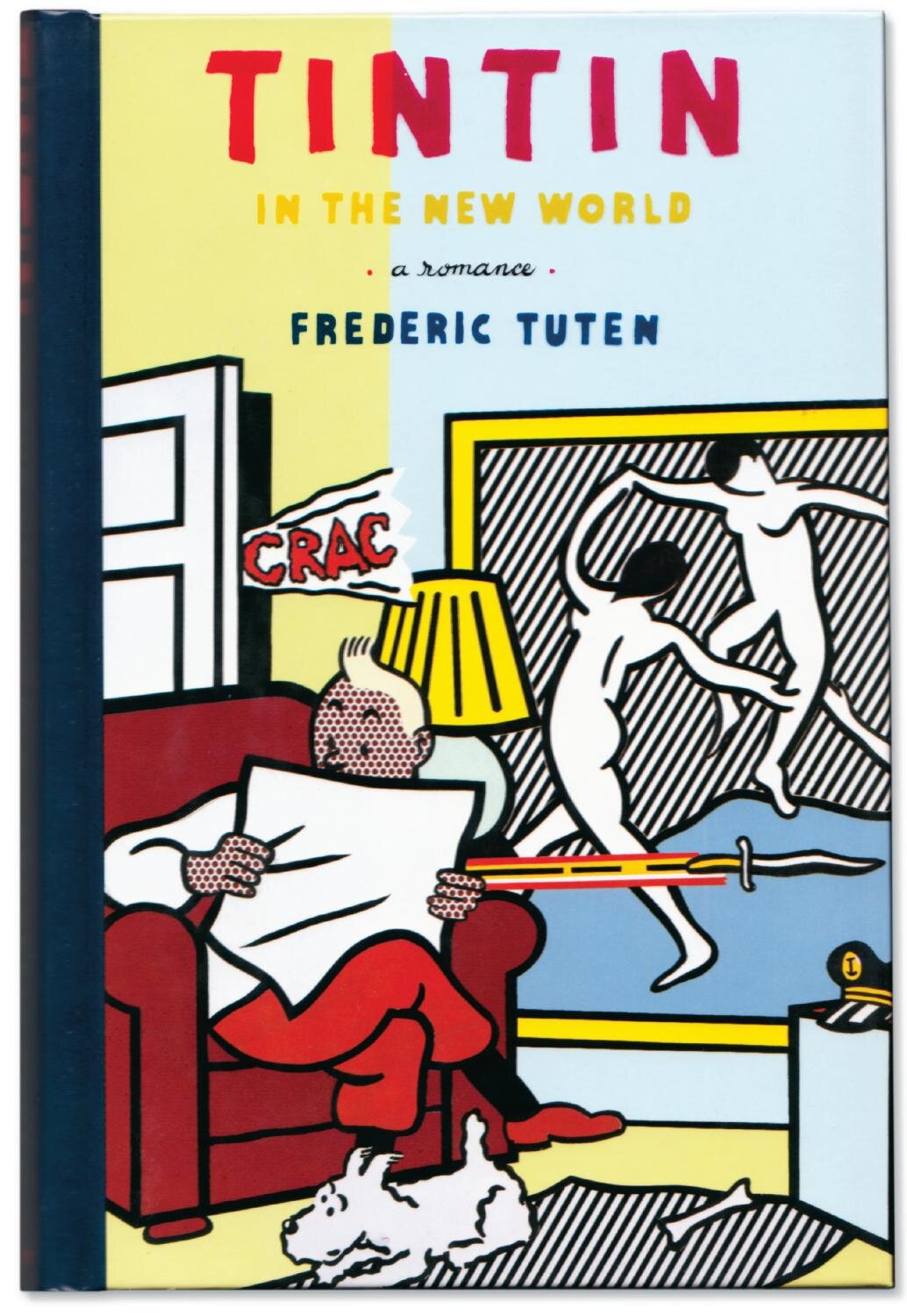

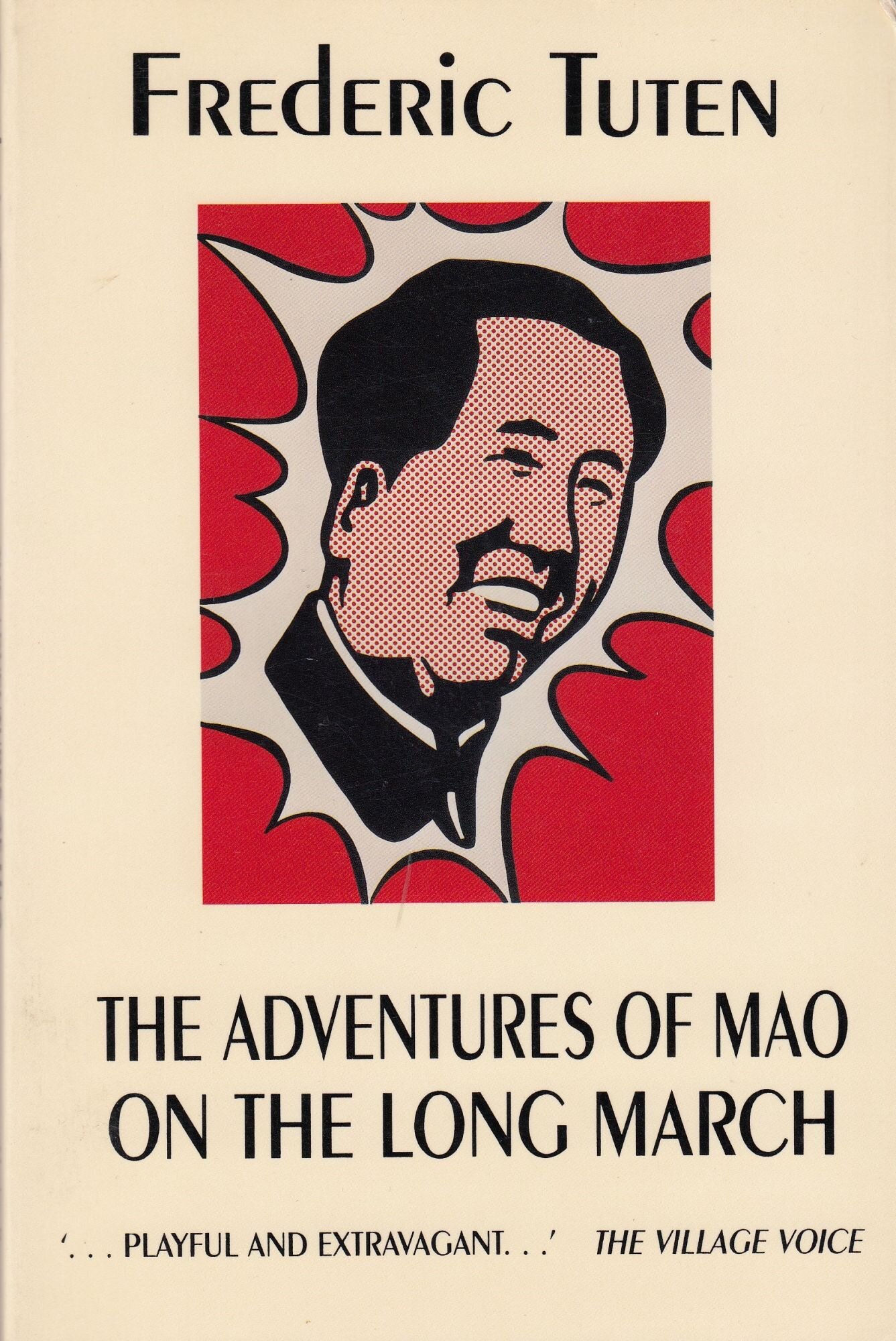

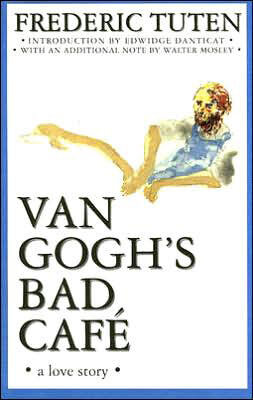

Frederic Tuten grew up in the Bronx. At fifteen, he dropped out of high school with aspirations to become painter and live in Paris. He took odd jobs and eventually went back to school, earning a Ph.D. from NYU. He travelled through Latin and South America, studied mural painting at the University of Mexico and wrote about Brazilian Cinema Novo. He taught at the University of Paris, acted in a short film by Alain Resnais, co-wrote the film Possession, and conducted summer writing workshops with Paul Bowles in Tangiers. The recipient of many awards for his writing, Tuten’s short stories, art and film criticism have appeared in ArtForum, the New York Times, Vogue, Granta and other publications. He has written about artists including John Baldessari, Eric Fischl, Pierre Huyghe, David Salle and Roy Lichtenstein. His books include The Adventures of Mao on the Long March; Tintin in the New World; The Green Hour; Van Gogh’s Bad Café; Self Portraits: Fictions, and most recently his memoir, My Young Life.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So in reading over your body of work, books like The Adventures of Mao on the Long March, Tallien: A Brief Romance, Tintin in the New World, they take in so many political and historical periods and often shuttle between the past and present. They have been very focused outward, although I know they have had autobiographical elements. Why did you choose now to write your memoirs? And what kind of conversations did you have with yourself in order to do it?

FREDERIC TUTEN

Well, I think it's time to say what I have to say about my life and what mattered to me in it, and with whom I shared it. And I think people were very surprised. The publishers were very surprised. They thought I would talk about the well-known people in my life, artists and painters and poets, and I didn't because the book takes place only between 1946 and 1964. So it's, I hope, part of an ongoing project. I hope I have enough energy and time left to further it and to say more about years and things afterward. In the beginning, I thought I have to say some things about my childhood. I usually deplore that. Childhood memories are sort of saccharin, and I shun it. I shunned it in my first novel. I didn't want to write an autobiographic novel, as many people do. I thought that was kind of–how do I say it?–cheap. So I didn't want to do this for a very long time, but then I thought, not just for myself, people in my life who has vanished and who were noteworthy in life. And I don't mean famous. I mean who gave a great deal to life, were interesting in life and maybe have vanished because they were not famous. There's no footnote in history for them.

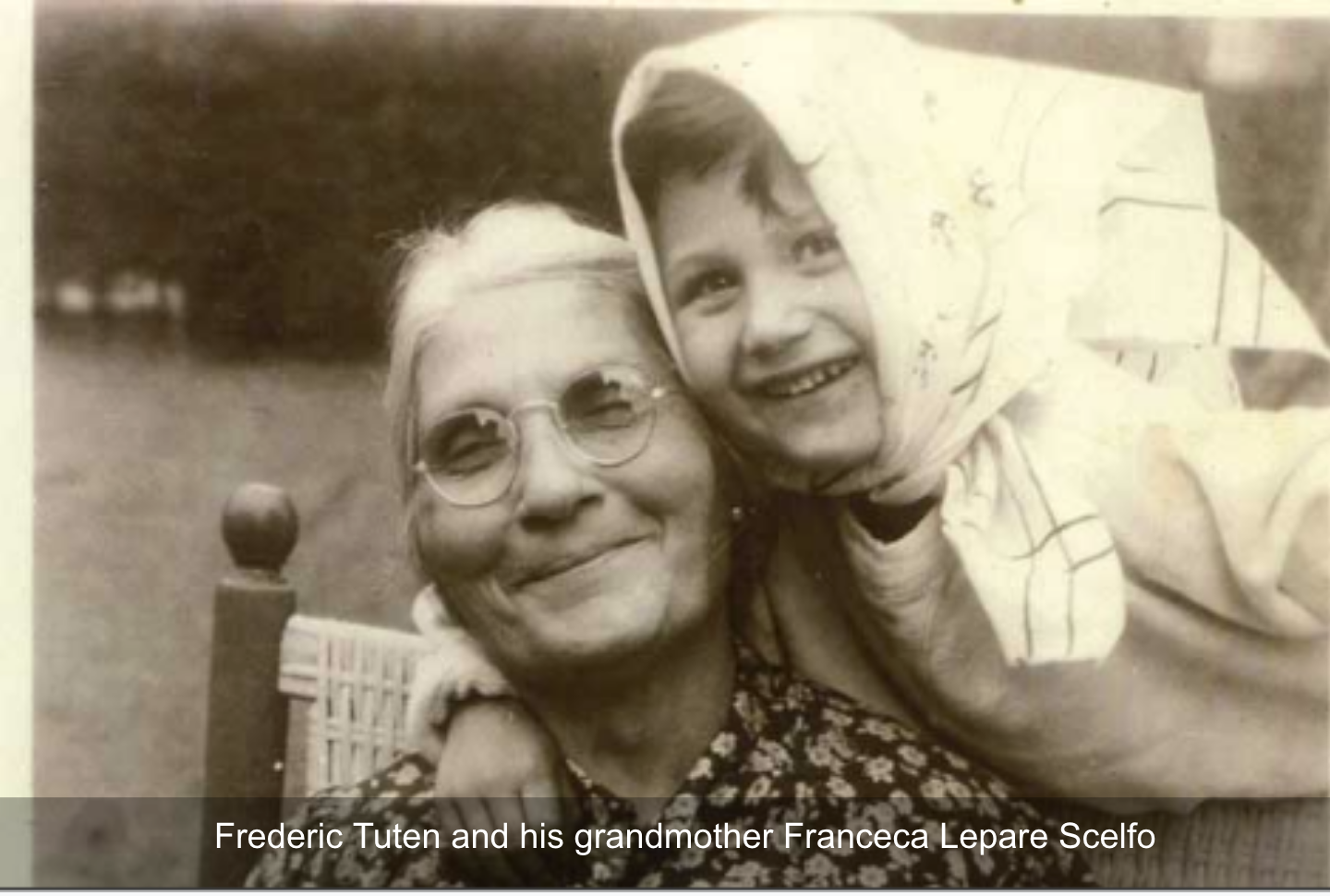

There's no place in history for them, but they were valiant and wonderful people, including my grandmother and my mother, who struggled so hard just to live and to support me as a young boy. My Italian family was so kind. Only in retrospect do I realize how kind and generous and growing and nurturing they were to me. And I didn't realize–when you're a kid, you don't really appreciate all that– but now I see it differently. Also, people in my life at City College, where I was an undergraduate, which was a never to be forgotten experience. It stayed with me so much and so deeply that I wanted to go back and never leave, and I did eventually go back as a professor. So I stayed the rest of my life. I was in my undergraduate years and then, even when I started going back to graduate school, I was teaching there. So it was immensely important to me. The people I met there, the professors I met there. You know, again, as I say, not all of them. They weren't Lionel Trilling, they weren't famous people, but they were really extraordinary people and, for the most part, profoundly brilliant and published writers, published people.

Hans Cohen, we worked on nationalism. People in the Philosophy and Literature departments, they were wonderful, so I told stories about them, but one person, an interesting man called Leonard Ehrlich, who at 35 published his first and only novel called God's Angry Man. It was a famous book, success at the time. He was he was immediately propelled into the highest literary world at the moment, people like Carson McCullers were his friends. And he never published another book, ever. He had done one novel, a beautiful novel God's Angry Man about John Brown the abolitionist and was a perfectionist. And so, I guess, so completely overwhelmed by the success of the first book that he must have thought that he had to measure or meet higher standards.

He gave himself high, high standards and to his students as well, myself as well. But I think what happened is he probably thought that he could not just write a good second novel. He had to write a great second novel. But the long and short of it is, I wrote about him, and I wrote about my friendship with him and my discovery that, in fact, he showed me these two manuscripts of two incomplete novels. Manuscript typewritten. Every one of the two novels, everything finished except the last chapter. The final chapter–he could not write the final chapter. I was 19 years old when I met him, and I couldn't tell him then. I didn't think then. I should have said to him, "I'll write it for you! Dictate it to me. Do anything but let go of it.” Anyway, he died in a kind of tremendous anonymity. All his documents are at the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. So one day I would like to go back and take a look. Maybe there's more about him than I know.

But that's the kind of memoir it is, about people like that. Like a man John Resko, who'd been in prison for 20 years. When he was a young man, he killed someone in a holdup when he was 17. Dannemora Prison for 20 years. I met him three years after he got out because he was a painter, an artist, and he was released, really because of the efforts of people to tell the world that he was a rehabilitated–not that he ever was a real criminal. So he did a hold-up with an older man on Christmas Eve, when he had no money.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And the Depression.

TUTEN

At the height of the Depression. No money. Nothing. He had been a merchant seaman as a boy, and there was no work.

There was nothing to ship out, and they were literally hungry in the Lower East Side. And he went out with this soldier guy to rob a grocery store. They thought it would be nothing to do, just nothing. The guy came at him with a bat, and the older man gave him a gun and said, "Shoot him." And he killed him, and that was it. They caught him right away, and the other man was electrocuted within six months, and John Resko had three reprieves. And the final one, a life sentence in Dannemora, one of the worst prisons, other than Alcatraz.

And we became great friends. He was like my father because I had no father. So the book is about people like that. It's about John Resko. [Resko wrote a memoir, Reprieve, which was adapted into a film starring Ben Gazzara. He is known for his paintings and work on The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.] It's about Leonard Ehrlich. It's about all these people and how they wove into my life and myself into theirs. It goes until 1964, so it could follow years as a young man in Mexico and then going to see Hemingway in Havana. I mean, it's kind of glamorous in a way, but it isn't the glamour I'm too interested in. I was really interested in the kind of Bildungsroman, I guess. [Tuten makes a face, as though the word is inadequate for what he wishes to express.] A novel of education of a young man who wants to come into life with very little means and support and finds a way for himself. That's what I wanted to do, and I wanted to say, also, for other people more like myself, impoverished as a child, what things there are to be happy about in life. What beautiful things there are in life. What beautiful books there are to know about. All that stuff.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I want to go back to your time meeting Hemingway, the more glamorous elements, but from this humble perspective and your time in Mexico, but if we could go back also and just talk a bit about your grandmother and your mother. There are beautiful stories about in My Young Life and also "Self-portrait with Sicily" [in Self Portraits: Fictions], which I love.

TUTEN

Oh, thank you.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Self Portraits: Fictions was almost the fictional first volume of My Young Life. Could you talk about the stories that you exchanged with your grandmother? I believe you spoke often in Sicilian?

TUTEN

Well, she spoke in Sicilian, and I answered her in English. That's how we did the world. My broken Sicilian and her broken English was so painful, but no, she told me stories about growing up. Mostly, it was dreams that she had. She was very dream-oriented. She believed the dreams were the authentic thing. If someone who had died came to her in a dream she would say, "Oh, you know, cousin so-and-so came to me in the dream last night. " I said, "Really, grandma?" And she said, "Everyone is happy there. And I should be happy because I'll be seeing them soon. And we were all happy together."

She believed that these dreams were visitations. Very interesting. I guess it's very Sicilian. Maybe it was that generation. Stories about when she was a child and in poverty in Sicily, and how she met her husband, you know, literally met him under a tree. She was standing under a tree in the hot sun, and they talked. I mean, simple stories, but touching stories and stories of how she had to come and her husband eventually had to leave because literally–I don't know if you call it the Mafia, but the bandits who are in that region–came after them because her husband was a Carabinieri. He was a policeman. And he went after them, and they came after him, and they said, "We will burn your house down. We'll kill you. We'll kill your children.

And they got out. They left and came to live in America. She was 26 old when she came here, and he was 48 or 50 almost and had no money and didn't speak English. Think about coming to America in those terms with nobody here. No money ahead. The humiliation of the language, not speaking it. Italians weren't treated very well in those days. They were looked down upon. I tell a little bit of it in the memoir.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

When I hear you speak, your Bronx accent comes out, but you're also genteel, and I think of you in a European manner.

TUTEN

It's so interesting to me, and I thought about this somehow. The difference between where we lived in the Bronx, which was basically a Jewish neighborhood. Almost everyone was Jewish. Mostly German Jews. Highly-skilled professionals, not doctors or lawyers, but they had skills, for example, like making crowns of teeth or grinding eyeglass lenses. And so they had semi-professional skills. They had enough money to get out of Germany just in time. My neighborhood was filled with those people, and they were basically people who read a lot, listened to music a lot. It was a whole world of culture that surrounded my neighborhood. A whole world of it. My mother read, but she read romances. She wasn't an intellectual. She had no college education, no high school education. She left grade school to help support her family. But about my family, the thing I realize now is that never did I feel, then or now, that there was anything but a great deal of courtesy and gentility among them. And if not literary sophistication or cultural sophistication, a certain worldliness and a certain kindness that I now understand deeper than I ever had before.

How they were with me, the generosity, the way they treated me and tried to nurture me. I remember when... I make this particular point. In the Bronx, the separation was the Bronx and then it was Arthur Avenue, which was Italian American. My mother didn't want to live there. She made a point to go to the Jewish neighborhood because she thought that that's where culture is, where education is, where books are appreciated. And she was right, to some degree, because the Arthur Avenue neighborhood, even now when I go back to look at it, there's not one bookstore. There's nothing. It's restaurants, tenements, even now.

I mean, I'm being crude about this, but I'm grateful for my family and the courtesy they showed to each other and the gentleness and the fineness of it. That's what I think really struck me. The sense of decorum, of warmth, of familiarity that wasn't too familiar. All of it, I saw growing up, and it moved me profoundly. But then when you speak about Europe, you know my dream was to be in Europe all the time. My dream was not Italy but to go to France. I dreamed of France since I was 15. I thought about France all the time. I read those books like Van Gogh's letters, I read Van Gogh's biography, and all the people who went there, the artists who gathered there. And I was 15/16 years old, and I dropped out of high school to go become a painter. How I was going to do that? I have no idea. What did I think?

But I was dreaming that I was going to save enough money and then go to Paris and become a painter. I dropped out of high school. I went to the Arts Students League. This is in the memoir. Foolishly, I didn't know anything about how to make a drawing of any sort, but I thought I'd learn. Europe, and the French culture especially, moved me. French literature and French painting via those painters who were there, either as guests like Van Gogh or even Gaughin.

Or Cézanne, of course, most importantly, but Paris was the center. And I guess I'm a Francophile. I still am, unapologetically. And I guess, in a certain deep sense, I'm a Eurocentric, unapologetically. And I'm a white male who was raised in a Eurocentric culture, and I believe very deeply in the culture of Europe, but that doesn't limit me. I traveled in South America. I've written about South American cinema. I love the cultures. I love them. I would have lived in Brazil, if I had the chance. I mean, the only other place I'd want to be would be in Brazil or Mexico City, in the old days. I'm just talking, forgive me.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Oh–just talking– I mean, it's an art, I think. It might be vanishing.

I don't know if it's indelicate to say, but beyond the merits of French culture–and you've had many important collaborations with Raymond Queneau, Alain Resnais, and all these other collaborations you've had and admiration for the painter Cézanne–do you feel sometimes your curiosity for the French culture, was it also, as you look back, maybe a desire to get closer to your father?

I know you wrote in Tallien...

TUTEN

Well, my father was a Southerner from Savannah, Georgia. Supposedly the roots of the family were French Huguenot, but my father I know never left the United States. He'd never been to Europe, I think. Once in his life, I know, he did some work in Greece. Some stuff he was doing was construction work. Why and how long he went to Greece? It was after the war. I guess they were rehabilitating Greece. But no, there was nothing. His culture was entirely southern. It was entirely a southern culture, except, and for what I think I've written about in Tallien, a deep pride I had for him was that he was, and in so far as none of us are or we all are, he was not racist. He left the South because he hated it. He hated the way the black people were treated, how they were lynched. He hated everything about it. He came North, eventually came North. I found out only much later in life that he wanted to be a writer. I didn't know that. Almost until his death bed, but nothing came of that. He came from a middle-class family of lawyers, and he hated that too.

He became a kind of a wanderer in the working class. I mean, that's how I see it. Where Gaughin went to Tahiti, the exotic world. My father left the middle class and joined the working class. That's what he did. No question of it. He felt–I'd see it–he would bring people he'd work with to the house at night and play cards and talk and drink. And he was in love with it. So, but that was his culture. Leftist culture. He was kind of a lefty. Union people. He loved that. He loved all that, and I admire for that to this very, very day. I admire him immensely for that. But the only European side of my family was my grandmother, my mother's side, the Italian side, who were both Sicilian. Again, my mother's sister was married to a man from Bari.

So it was all Southern Italians, but really nothing crude about it. There was something, I realize now how extraordinary they were. Appreciative of culture even if they didn't have a resounding avenue to it, but they understood feeling for it. They loved opera for it. If they could listen to it on the radio or snippets of it, they could be thrilled.

But that's it. My love for Europe had to do with, I guess, a wish to be different. Not to be in the Bronx.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Have you ever felt that you were born in the wrong country?

TUTEN

Well, I'm not sure I was born in the wrong country. I mean, I'm very happy I was born here. Because it is wonderful to have more than one culture, as you know. It's a great thing in life. It's a wonderful thing in life.

If you know other languages, it's stupendous because it gives you some access, both in reading and fluidity of places, but also to know that you can have two exciting places to be in. Two exciting languages and two exciting cultures and two exciting places to visit. That's what I love, mostly. I don't think I was born in the wrong country. I wasn't really born in America. I was born in the Bronx.

That's a different planet, too. You know, what I mean? New York City, but not even New York City. In the Bronx, which was its own world with its own system of behavior and thought and food. I was born in the right country. I was born in the country of the Bronx.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think it is definitely, as you speak about it and as I experience your writing, I don't know if it's just your grandmother or your mother, but this idea of this kind of dreamlike description of things. You spoke about how she felt dreams as though they were reality, and I see that comes again and again in your fiction.

TUTEN

Thank you. Realist fiction is interesting enough, if it's done very well. Sometimes it's just not done very well, like most fiction, but I think it's profoundly limiting.

I mean, to be to be concerned about verisimilitude or to be concerned about the way people naturally speak and try to make dialogue sound like the way people speak doesn't interest me at all.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Well, we have life for that.

TUTEN

We have life for that, as someone once said. And also, the world is more mysterious than just the sputtering of a cigarette in a gutter. It's profoundly mysterious, and I think there has to be a language attuned to it or a language that tries to reach toward. And situations that reach toward it, not just faithfully describe like a photograph. If that's even a faithful description of a surface reality, where supposedly events occur underneath that have mystery. It's not my way. I don't believe in that. And I am very sad to think that most American writing is so limited, so profoundly limited now. It's not interesting to me. I don't think there is much writing anywhere else that I can find as... except maybe Latin and South America.

Bolaño, as my friend would say, Bolaño "is the joint". He's great. And it's powerful and wonderful and strong writing. It comes out of that other world. I don't see it today, here in America. I just don't. I don't see it. I see kind of, maybe well-made novels. They subscribe to the formulas of MFA writing. The arc and the plot and the character and likable characters. That's dreary and awful. It's dreary. To make novels where you have likable characters, well, you'd never have Moby Dick, you'd never have Crime and Punishment, you'd never have most of the novels that make lunatic people–like Cervantes has. It's upsetting to me. I'm sorry that young people don't have enough visitations of other literatures and cultures.

Yes, the dream world is powerful to me. Not that I see myself as surrealist where the dreams are the center of my writing, but somehow the elements in which oddness can occur with credibility. The odd, the unusual, the mysterious, the unexpected, the surprise... Those are the things that interest me in characters and events. Well, for example, in Van Gogh's Bad Cafe where you have a man in the Lower East Side, where I lived most of my life now, my grown-up life. And a photographer who one day sees a woman come across through a wall. And she's coming from the 19th century. People will say–What kind of stupid thing is that? How can you come across a wall from the 19th century? Well, you can in fiction, if you write it well enough. I hope I have. So those are the things I'm interested in.

It's so awful and pretentious for me to say it, but I want to get to the core of things, as much as I can, to what I know of it. I want go to the center of things. I don't want to go around it. I don't want to tell the surface of it. I want to go to something that's deep in our hearts. All of us, deep in our hearts. I'm not religious. I don't believe, maybe I'm agnostic. And it's hard to say, but I believe somehow in the soul. I don't know where it is in us. I don't know if it's immortal, imperishable, but I feel that, and I feel that I want to go to the soul of literature in some deep way. I want to go to the soul of living. As I'm talking to you, I get embarrassed.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think that it's important. I think the importance of the arts and the humanities is that it nourishes this part of ourselves that we have to keep hidden most of the time.

TUTEN

Absolutely, if literature doesn't nourish us, what's the point? If literature doesn't nourish us in an unfathomable way. I don't know how it does it exactly. It doesn't make us better people. It doesn't make us much nicer people, necessarily, but it does nourish in a way that no other thing quite does. I mean, not quite. You have other nourishments, but great literature just fills us with the feeling of–not the answers for life–but the wonder of it.

And the joy of it. That we can create outside of ourselves things who are not without us, but they're us. Fiction, a literature, a poetry that nourishes others, whoever we may be. I mean, like Wagner with his rotten personality and terrible character and miserable anti-Semitism–but look what he gave us. That's what we're talking about, a transcendental art. Art that transcends itself and gives us a sense of transcendence. That's what I'm interested in.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What are your thoughts of the future of communication and how technology is changing the way we communicate and interact with our imaginations?

TUTEN

That's a very good question, and I really wish I had some knowledge of it. All I know is that when I'm walking in the street, I see people walking on the street texting each other or on the phone with each other or sitting in restaurants and texting. I say, "What planet am I on? I'm living in the 19th century, not even the 20th century. You must have seen it. Women and men sitting at a table together texting instead of talking to each other. I can't imagine what people on the street, on the phone all the time, literally almost walking into you. What is there to say? In a text? Are you going to talk about the novel you read? Or just the boyfriend you met?

But I don't know what that means in terms of writing, in terms of the future of literature. If people are just interested in that all the time. Even television seems like an old fashioned thing. Who knows what is going to happen? Let's just hope we survive. Things seem so dire.

I'd like to believe that the art, literature, and music that matters will matter. It doesn't matter to a vast amount of people. It will matter to people for whom it matters, who need it, who can't live without it, who cannot live without beautiful music or painting or literature or poetry. They can't live without it. They'd be starved. Now that's what I don't know. I don't know if people are starving without it right now. I just don't know. I don't know if young people who are texting each other 24 hours a day are starving. I don't know what they think about. I teach young students who want to write. So I know what they're thinking about, but they're a minority of a minority. Or painting. It's still going on. People are doing it, in spite of everyone telling you that painting had died 25 years ago. Whatever. "It's immaterial. It doesn't

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

That's a very beautiful, important observation. I think that as long as we have people who are committed like you, people committed to literature and the arts and other mediums and communicating the wonder of that to others...

TUTEN

It’s always been a few people, anyway. Yet it’s always been appreciated and those who cared carried it on.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process.