Courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art, New York

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Welcome to The Creative Process. Let’s start off with one of your most iconic well-known series of works Breast Stupas (2000-2001). How did the series come about?

PINAREE SANPITAK

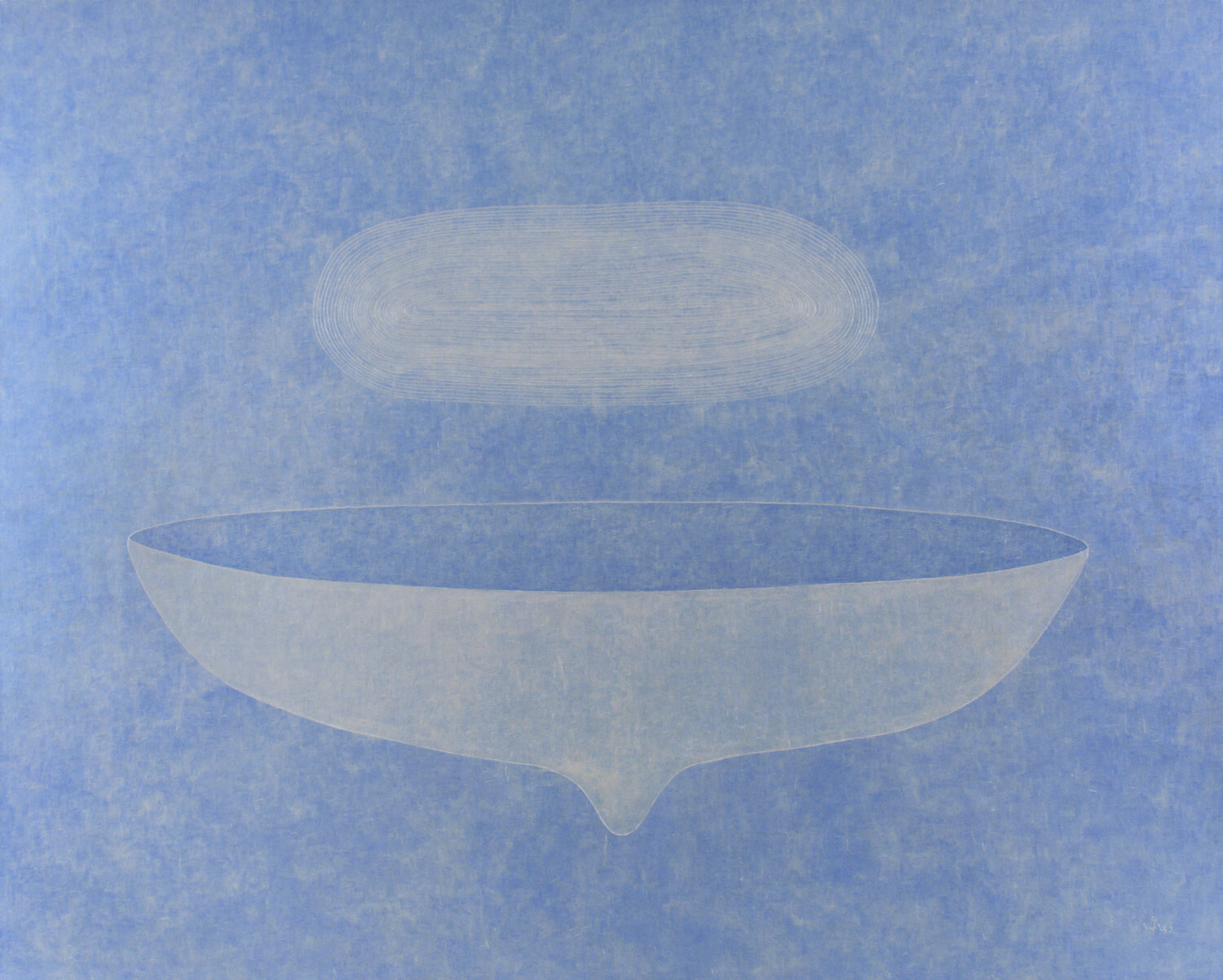

I started my breast works in 1994 two months after I gave birth to my son. I created a symbol or metaphor for the self, talking about my experience as a mother and as a woman. The first breast works from 1994 were all single and upright, as a monument to womanhood. A year later the breast works were turned upside down, elongated, sagging, kind of coming back to reality. Then the body appeared. I thought maybe I’ll move onto something else. I felt there was so much to explore, so I kept on at it. The breast form has evolved and turned into the body becoming a vessel, the breasts becoming clouds, fruits, offerings….

At one point, my life felt more grounded and secure, so I coined this term ‘breast stupa’ for an installation comprising silk panels. I took a perfect 5 m long pieces of silk, pulled threads out of it to form the image in the middle. They were earth tones in black, grey and beige, and they hung from the ceiling so you could walk through them. They barely touched the floor, so they fluttered a bit. It was a kind of sanctuary. The idea was to combine the concept of the sensual and the sacred together. I work visually, but I do like to play with texts and with the titles of my works, in a way to give hints. The work Breast Stupas was made in 2000 to 2001. So you can see it has slowly evolved since 1994. It grows with me.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I want to delve deeper into this very startling thing you’ve put together: the breast with all its symbolism and the stupa, which has all these religious connotations in Thailand. What was the reception in the beginning when you created these series of works?

I didn’t really have any problem. But as you can imagine, showing the breast in Thailand is taboo. Even in fashion shows or photography, this was frowned upon thirty years ago. Now it’s looser. But if you remember, in olden times, women walked around bare-breasted. When I moved back from Japan in the late ‘80s, I remembered this elderly lady in her ‘80s at my grandfather’s house walking around with just a sarong cinched at the waist. Nothing on top. It’s very natural for the female body. So, I combined it with the stupa. Looking at the stupa, it can resemble the breast. We’re taught a certain way to take things in, and this is how the brain becomes confined. From the beginning, starting with my works in 1985, it’s about breaking away from what you actually see, breaking away from a preconceived perception.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

How then did the creative process happen for you of this morphing of the breast into clouds and vessels? What led you to that?

SANPITAK

The shapes come naturally to me. I work back and forth in two and three-dimensional works. There’s a dialogue between the works themselves, between the works and me, and also with what’s happening around me.

The clouds, for example: the idea just appeared one day. I think it was a hot summer day in Bangkok in 2007 or 2008. I was doing cloud figures with the breast in watercolour and later a friend told me there’s a Pali-Sanskrit word ‘payotara’, which means ‘beholder of water’ and ‘beholder of milk’. So, the concept of the breast and clouds already exists. If you think about it, it does relate. The breast is unpredictable, sensual, a provider of sustenance and of drink. Not unlike clouds. There was a subconscious link for me.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You were mentioning how you work back and forth from two to three dimensional works, and also in various different mediums. For example, Breast Stupa Cookery (2005) relating to food and Breast Stupas (2001) were silk hangings, is that correct?

SANPITAK

Yes. After I created Breast Stupas, the silk hangings, I started Breast Stupa Cookery in 2005 which is still ongoing. I wanted to incorporate food into my work. I love eating and I love cooking, and my studio is between the kitchen and the garden. It felt like a very natural progression, because since 2000, I’ve been working with a variety of materials. I was baking a lot also at the time, making bread. So I thought maybe I could use bread dough, because it was malleable like clay. But it didn’t feel quite right yet. I was also making ceramics at the time. One day it just clicked and I thought why not make cooking molds? I invited different chefs to work with these molds, as a way to dialogue and ask people what they thought about these breast stupa forms. Food as an art medium and a connection. We have held about 30 events so far.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

How many people usually attend?

SANPITAK

It varies every time. It could be a sit-down dinner for 8 to 10 people, or a buffet for an opening for 200 to 300. It can be a tea ceremony, or a wedding. I don’t dictate to the chefs what to make, so the food choices are entirely up to them. I also learn from the chefs because they are artists themselves, so the tools have grown as well. Starting from ceramic molds, I went on to make aluminium molds in different sizes and shapes, moved onto glass, and then plastic. We got them made in plastic and glass because we were making chocolates and they had to have a smooth texture. We also made cookie cutters. Each time we came up with something different. The presentation matters too as well as the way we eat the food.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

When you move onto a new medium, how do you approach the process? Do you find that you really have to understand the material?

SANPITAK

Usually if I see a beautiful material I’m drawn to, I’ll get some. My first sculpture pieces Breast Works/Untitled (1994), Womanly Bodies (1999), Confident Bodies (1996-1997) were made of mulberry fibre, from the first pounding before we make paper pulp, so they come as these fibrous sheets. At first, I thought of collage, but they’re so beautiful I didn’t want to paint over them. They sat in my studio for 2-3 years and then finally, I sewed them together to create shapes. They look fragile but they’re actually very sturdy. There’s a structure in the fibre itself. It worked perfectly as sculptures.

The Flying Cubes (2010-2011), for example. I was given this origami shape of cube with wings in Tokyo. I was so intrigued. The Japanese like to give out souvenirs, and I was given this cube in a restaurant. This simple form of a cube with wings just intrigued me. I kept folding them for 2 to 3 years before I was able to release them in my own interpretation, first as scarecrows in rice paddies, standing rattan sculptures and then as paper sculptures in the interactive sound installation Anything Can Break (2011).

In that work, there were about 6000 paper origami flying cubes and 200 breast clouds in clear and sand-blast glass and 16 sensors to activate sounds tracks in sixteen pods around the installation. Usually, I place it according to my height (230 to 240 meters above ground), suspended from the ceiling. Tall people would be able to reach if they want to. I started this work in 2007 when I got the opportunity to work with Murano glass. The first concept was all in glass, and the idea of having glass above your head is like having this fragile existence above your head, but it was too expensive, and I couldn’t finalise the way to hang the Murano glass in a stable way, it was simply too thick. Then, along came the invitation to participate in the conference at the MET called Art Beyond Sight, but it wasn’t finished in time for 2009. I finished it finally in 2011, and it was perfect, because the paper origami helped with the acoustics of the piece. At the same time, I was creating these breast-shaped clouds, and to me, the two works related to each other as a skyscape. The largest version of The Flying Cubes was about 100 sq metre, and the paper origami came in shades of grey, so the grey and silver was like lifting up a painting above your head.

The sound was the same idea as Breast Stupa Cookery. I invited different composers and musicians to compose music to respond to the work. So far, I have two tracks of music: the first by American composers Jeffrey Calman, Avi Sills and Amir Efrat. The tracks are more classically based with vocals and percussions.

The second set I worked with Australian sound media artist Tim Gruchy. The two sets are quite different. I hope I can have more sounds added. When I have two sets of sounds, we would set it so that the sounds change every 10 minutes. When you enter the installation, you can have a different experience.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Sounds like a very immersive experience. Talking about immersive installations brings me to Temporary Insanity (2004), which I’m really intrigued by, because it’s multi-sensorial, and yet very playful. The name itself is very evocative as well.

SANPITAK

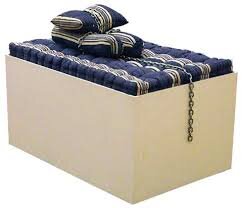

Temporary Insanity happened in 2004, quite some time before Anything Can Break (2011). From 2000 onwards, I became more interested in creating installations that explored sensory perceptions, starting from Noon Nom (2002), exploring our sense of touch, and then came scent with candles to Temporary Insanity, exploring sound and movement. It’s a simple idea - how to make these soft sculptures move when there is sound. We had to test a lot. I didn’t want the pieces to be anchored to the floor. It took quite some time, and I worked with a technician and my brother-in-law also.

The shapes weren’t just breast shapes, there were balls as well. It’s not just female. It was meant to relate to different ages and genders. It’s more about emotions. It’s funny.

It’s activated by movement. When there are footsteps, or sounds, a microphone links it to a motor and a weight, and the weight swings and the shapes start to shake.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What’s been the most surprising audience responses to Noon-Nom or Temporary Insanity?

SANPITAK

At first people were reluctant to touch or play with them. Once the audience broke through that barrier of no-touch with respect to an artwork, they let go. What I’m pleased with is that I can see the audience spending a longer time with the work than normal.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What’s interesting to me is the public/private divide. A tactile experience, or even just laughter, can be a very private response, and yet it’s happening in this museum space, a public space. Was that your intention as well? How serious a museum gallery can be, yet you have all these playful shapes you can interact with.

SANPITAK

Yes. But it’s not just play, it’s also to connect with these forms and figures. For example, with Noon Nom, when I was giving a talk in America, I showed a shot of the installation in a mall in Thailand, surrounded by kids and other members of the public, and you can also see a shot from the floor above. A member of the audience said to me, you probably couldn’t do this in America, having kids play with breasts like that. Mothers can get scolded if they breastfeed in public. I breastfed my son until 2, and when we were travelling, I would breastfeed him everywhere. But this is not the norm, you hardly see this, the exposing of the breast even as basic and natural as a mother breastfeeding her child.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

This is a great point to segue into the discussions about these terms I see thrown around a lot in art historical discourse about your work: ‘female artist’, ‘Asian female artist’, ‘feminism’. How fluid or contingent are these terms to you? Do you feel your works resist that categorisation? Would it be reductive to adhere to these categories?

SANPITAK

When I started my career 30 years ago, the term ‘feminist’ was very different from now. I would admit that I didn’t want to be confined to that category at the time, so I didn’t try to relate to it, I’m just doing what I’m doing as a female artist. Yes, I am a feminist, but it’s very different now. I’m reviving this concept in the Red Alert series (2018) because the issue is still ongoing, more urgent and more pertinent.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It’s been a discussion topic for a long long time but it has also risen a lot to the fore more recently because of social media – the female body is a constant site of contestation in public discourse and all other disciplines. Has your artistic process changed in terms of exploring the female body?

SANPITAK

At this point, I think my works can explain themselves better. It’s not just about the breast, it’s also about the body, whether part or whole. It took some time. It’s really looking at it from all different angles, and it takes time to make work. But then with The Hammock, Anything Can Break, The Flying Cubes, Ma-Lai, (2015) or these more recent installations that relate to the public and architecture: Mats and Pillows (2017), The Roof (2017), The House is Crumbling (2017), it’s not just about the female body but also how all our bodies interact and share and exchange. How one can make the best out of each body.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Hanging by a thread is a work that in more straightforward ways addressed an urgent social issue. How did you come to create that and what were you hoping to convey?

SANPITAK

I created that work in 2011 when we had the big floods in Thailand. I had to close my studio even though fortunately it was not flooded. I had to move all my works and find other ways to create work. So working with these fabrics was perfect for that situation. I was inspired by the content of the Royal sponsored relief bags, which apart from canned foods and utilities, it had this printed cotton cloths called paa-lai for women with separate designs for men, which I thought must have been so comforting for the people affected. I made hammocks with them because the idea of the hammock is for resting, for laying down, for a baby to be placed in, for a body to slow down. You can also see the body without having an actual body there. I hung it so that you could sit or lay on them. And I also meant to play with the words Hanging by a thread, portraying also the unstable social and political issues in Thailand at the time, including the nature and environmental issues, surrounding this.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Coming to 2017, The Roof in the Winter Garden in New York, how did that commission come about? What was the work and what was the reception?

SANPITAK

I’ve been showing works with a gallery in New York, Tyler Rollins Fine Art, since 2010. It was a connection Tyler Rollins set up with Brookfield, the property management company that owns lots of properties in the United States and internationally, and it has a section called Brookfield Arts, which organises art commissions, theatre, performances etc. in the buildings they own. I visited the Winter Garden twice, in 2014 and 2015, and I was really intrigued by the space, the skyscraper, the palm trees; initially it felt like a ‘spiritual’ place, although that is not quite the right word. At first I suggested something that would link to 9/11 as the building is right across from Ground Zero but they said they wanted to move on. It’s a huge atrium, and I could pick anywhere in the area to work with, but I was so drawn to the trees, so I wanted to work around the issue of refugees, immigration, American politics and New York itself. At first I proposed Mats and Pillows but it proved to be too difficult with foot traffic. So in the end we settled on The Roof. A roof over the head to share instead of a shared space on the floor.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You said that it had to meet with a lot of New York regulations?

SANPITAK

Yes, I didn’t realise that. It had to pass New York City Fire Dept. regulations. We had to test the materials and have it treated.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Tell us about your collaboration with The Singapore Tyler Print Institute?

SANPITAK

This is my second phase. I came first time in May. I’ve visited STPI many, many years ago and I always wanted an opportunity to come work here. This is like a dream residency for an artist. This is my 2nd print workshop. Usually, I don’t have a fixed idea what I’d like to achieve in a residency, leaving it open, but there’s some link usually with my corpus of work at the time. In 1999, I was creating Womanly Bodies, so at that print residency in Darwin, I made a series of print works based on those sculptural works. This time I’ve been working on the red paintings in Bangkok, and I wanted to bring that into the print series. In the Red Alert! series, I do use the forms and symbols I’ve been using all these years, but portray them from a different viewpoint, a different light. I’ve been trying to collage these ideas, forms and images into a new narrative.

Another unique aspect of STPI is that it also has a paper mill. I was first drawn to the paper mill and started with the paper making process first. I try to combine the print technique and my images and the printmaking process.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Is the experimentation process quite frustrating if it doesn’t work out to what you expect?

SANPITAK

The only frustration I had in May was I couldn’t draw on Mylar (the plastic sheet to make silkscreen). It was too artificial, too industrial, and too shiny. It took a while to break through that.

Normally, when I work with another master, I usually give them the space to add their expertise and contribution as well. So it’s a developing process.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

How do you see education intersecting with the visual arts and the humanities?

SANPITAK

Apart from educational programmes and initiatives that galleries and museums can create, the artworks themselves can provide an experience, and for some of my works, you don’t need a lot of information to get into them, because they’re open and interactive. It’s not about educating, it’s about letting go and trusting your instincts. If people are more open, free to exchange and share, it will be a step in the right direction. With artworks you have to be open-minded. They’re open to interpretation.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Are you fond of reading? What’s your favourite reading material?

SANPITAK

Cookbooks and Haruki Murakami. I’m reading Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I love Murakami! Thank you, Pinaree! It’s been a real pleasure.

SANPITAK

My pleasure.